Blog Archives

Q: How do you select a photograph to use as reference material to make a pastel painting?

A: Like everything else associated with my studio practice, my use of photographs from which to work has changed considerably. Beginning in the early 1990s all of the paintings in my first series, “Domestic Threats,” started out as elaborately staged, well-lit scenes that either my husband, Bryan, or I photographed with Bryan’s Toyo Omega 4 x 5 view camera using a wide-angle lens. Depending on where I was living at the time, I set up the scenes in one of three places: our house in Alexandria, VA, a six-floor walkup apartment on West 13th Street in New York, or my current Bank Street condominium. Then one of us shot two pieces of 4 x 5 film at different exposures and I’d usually select the more detailed one to be made into a 20″ x 24″ photo to use as a reference.

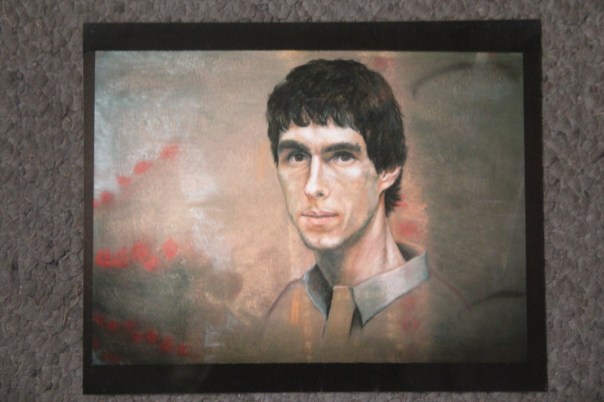

Just as the imagery in my paintings has simplified and emptied out over the years, my creative process has simplified, too. I often wonder if this is a natural progression that happens as an artist gets older. More recently I have been shooting photos independently of how exactly I will use them in my work. Only later do I decide which ones to make into paintings; sometimes it’s YEARS later. For example, the pastel painting that is on my easel now is based on a relatively old (2002) photograph that I have always liked, but only now felt ready to tackle in pastel.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 65

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

To create demands a certain undergoing: surrender to a subconscious process that can yield surprising results. And yet, despite the intuitive nature of the artistic process, it is of utmost importance to be aware of the reason you create. Be conscious about what you are attempting or tempting. Know why you are doing it. Understand what you expect in return.

The intentions that motivate an act are contained within the action itself. You will never escape this. Even though the “why” of any work can be disguised or hidden, it is always present in its essential DNA. The creation ultimately always betrays the intentions of the artist. James Joyce called this invisible motivation behind a work of art “the secret cause.” This cause secretly informs the process and then becomes integral to the outcome. This secret cause determines the distance that you will journey in the process and finally, the quality of what is wrought in the heat of the making.

Anne Bogart in and then, you act: making art in an unpredictable world

Pearls from artists* # 60

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

For an artist, it is a driven pursuit, whether we acknowledge this or not, that endless search for meaning. Each work we attempt poses the same questions. Perhaps this time I will see more clearly, understand something more. That is why I think that the attempt always feels so important, for the answers we encounter are only partial and not always clear. Yet at its very best, one work of art, whether produced by oneself or another, offers a sense of possibility that flames the mind and spirit, and in that moment we know this is a life worth pursuing, a struggle that offers the possibility of answers as well as meaning. Perhaps in the end, that which we seek lies within the quest itself, for there is no final knowing, only a continual unfolding and bringing together of what has been discovered.

Dianne Albin quoted in Eric Maisel’s The Van Gogh Blues

Comments are welcome!

Q: How do you organize your studio?

A: Of course, my studio is first and foremost set up as a work space. The easel is at the back and on either side are two rows of four tables, containing thousands of soft pastels.

Enticing busy collectors, critics, and gallerists to visit is always difficult, but sometimes someone wants to make a studio visit on short notice so I am ready for that. I have a selection of framed recent paintings and photographs hanging up and/or leaning against a wall. For anyone interested in my evolution as an artist, I maintain a portfolio book with 8″ x 10″ photographs of all my pastel paintings, reviews, press clippings, etc. The portfolio helps demonstrate how my work has changed during my nearly three decades as a visual artist.

Comments are welcome!