Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 590

Barbara’s Studio: when you fall in love with pastel!

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

We see again and again in the lives of special artists a profound youthful infatuation with their medium, with everything and anything connected with it – the good, the bad, the indifferent. If books have mesmerized them, they will read everything; if painting, they will frequent every gallery, running to every visiting show. They may have no idea that they are about to devote their life to that medium; they simply fell in love. The actor Len Cariou said:

“I didn’t have any thoughts about being an actor. I always was an actor. I’d go to films every Saturday. I had an insatiable appetite for films. You could see four films and a serial for half a buck. In 1959 when I read an ad in the local paper, ‘Young actors wanted for summer stock,’ all of a sudden I knew; there was a crunch in my head.”

… The artist is transported by his medium, is delighted and astonished. That his medium is able to speak to him in this way is almost a proof of the existence of god, or at least a special affirmation in the realm of the spirit.

Eric Maisel in A Life in the Arts: Practical Guidance and Inspiration for Creative and Performing Artists

Comments are welcome!

Q: How do you account for your intense compositions? (Question from Robin Plati via Facebook)

A: If I do say so, composition is something I’m known for. During the months I work on them, I devote many hours to looking at the painting on my easel and figuring out how to move the viewer’s eyes around in interesting ways. Everything you see is carefully worked out after hundreds of studio hours. Finished pastel paintings always have an inevitability about them. Change one detail and the entire composition is thrown off.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 433

Chatting with Jenny Holzer. It looks like she did not want her picture taken, but she was actually waiving.

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

…Two positions exist, the artistic and the commercial. Between these two an abiding tension persists. The eighteenth-century American painter Gilbert Stuart complained, “What a business is that of portrait painter. He is brought a potato and is expected to paint a peach.” The artist learns that the public wants peaches, not potatoes. You can paint potatoes if you like, write potatoes, dance potatoes, and compose potatoes, you can with great and valiant effort communicate with some other potato-eaters and peach-eaters. In so doing you contribute to the world’s reservoir of truth and beauty. But if you won’t give the public peaches, you won’t be paid much.

Repeatedly artists take the heroic potato position. They want their work to be good, honest, powerful – and only then successful. They want their work to be alive, not contrived and formulaic. As the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch put it: “No longer shall I paint interiors, and people reading, and women knitting. I shall paint living people, who breathe and feel and suffer and love.”

The artist is interested in the present and has little desire to repeat old, albeit successful formulas. As the painter Jenny Holzer put it, “I could do a pretty good third generation-stripe painting, but so what?

The unexpected result of the artist’s determination to do his [sic] own best art is that he is put in an adversarial relationship with the public. In that adversarial position he comes to feel rather irrational for what rational person would do work that’s not wanted?

…Serious work not only doesn’t sell well, it’s also judged by different standards. If the artist writes an imperfect but commercial novel it is likely to be published and sold. If his screenplay is imperfect but commercial enough it may be produced. If it is imperfect and also uncommercial it will not be produced. If his painting is imperfect but friendly and familiar it may sell well. If it is imperfect and also new and difficult, it may not sell for decades, if ever.

Ironically enough, the artist attempting serious work must also attain the very highest level of distinction possible. He must produce Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov but not also The Insulted and Injured or A Raw Youth, two of Dostoevsky’s nearly unknown novels. He is given precious little space in this regard.

I daresay, this last is why I devote my life to creating the most unique, technically advanced pastel paintings anyone will see!

Eric Maisel, A Life in the Arts: Practical Guidance and Inspiration for Creative and Performing Artists

Comments are welcome!

Q: What is more important to you, the subject of the painting or the way it is executed?

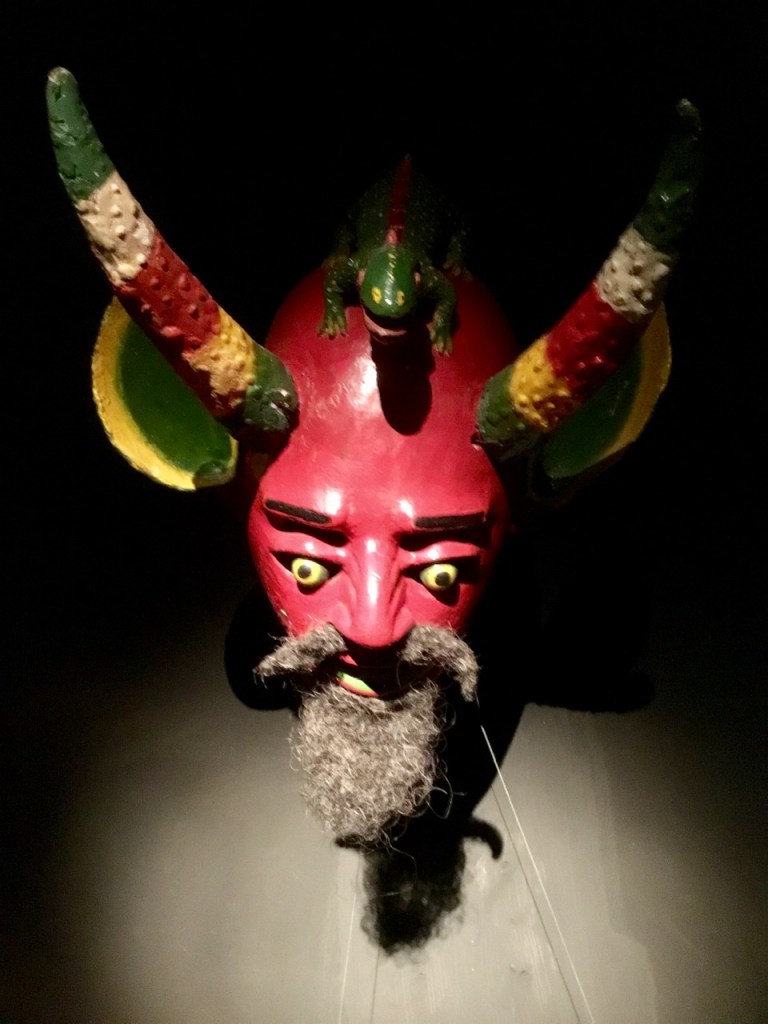

A: In a sense my subject matter – folk art, masks, carved wooden animals, papier mâché figures, toys – chose me. With it I have complete freedom to experiment with color, pattern, design, and other formal properties. In other words, although I am a representational artist, I can do whatever I want since the depicted objects need not look like real things. Execution is everything now.

This was not always the case. I started out in the 1980s as a traditional photorealist, except I worked in pastel on sandpaper. (For example, see the detail in Sam’s sweater above). As I slowly learned and mastered my craft, depicting three-dimensional people and objects hyper-realistically in two dimensions on a piece of sandpaper was thrilling… until one day it wasn’t.

My personal brand of photorealism became too easy, too limiting, too repetitive, and SO boring to execute! In 1989 I had at last extricated myself from a dull career as a Naval officer working in Virginia at the Pentagon. Then after much planning, in 1997 I was a full-time professional artist working in New York.

Certainly I was not going to throw away this opportunity by making boring photorealist art. I wanted to do so much more as an artist: to experiment with techniques, with composition, to see what I could make pastel do, to let my imagination play a larger role in the paintings I made. I was ready to devote the time and do whatever it took to push my art further.

After spending the early creative years perfecting my technical skills, I built on what I had learned. I began breaking rules – slowly at first – in order to push myself onward. And I continue to do so, never knowing what’s next. Hopefully, in 2018 my art is richer for it.

Comments are welcome!

Q: How do you feel about accepting commissions?

A: By the time I left the Navy in 1989 to devote myself to making art, I had begun a career as a portrait painter. I needed to make money, this was the only way I could think of to do so, and I had perfected the craft of creating photo-realistic portraits in pastel. It worked for a little while.

A year later I found myself feeling bored and frustrated for many reasons. I didn’t like having to please a client because their concerns generally had little to do with art. Once I ensured that the portrait was a good (and usually flattering) likeness, there was no more room for experimentation, growth, or creativity. I believed (and still do) that I could never learn all there was to know about soft pastel. I wanted to explore color and composition and take this under-appreciated medium as far as possible. It seemed likely that painting portraits would not allow me to accomplish this. Also, I tended to underestimate the amount of time needed to make a portrait and charged too small a fee.

So I decided commissioned portraits were not for me and made the last one in 1990 (above). I feel fortunate to have the freedom to create work that does not answer to external concerns.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Was there a defining moment, meeting, or event that convinced you to pursue an artistic life?

A: There was not a defining moment per se, but looking back now, I’d say that because the Navy assigned me to a series of boring office jobs instead of letting me fly, I became determined to find a vocation infinitely more rewarding and more interesting to devote the rest of my life to. I came to this realization over time, rather than in a single moment.

Comments are welcome!