Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 603

With friends in Alexandria, VA

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The annals of art and science are full of studies of men and women who, desperately stuck on an enigma, have worked until they reached their wit’s end, and then suddenly made their longed-for creative leap of synthesis while doing errands or dreaming. The ripening takes place when their attention is directed elsewhere.

Insights and breakthroughs often come during periods of pause or refreshment after great labors. There is a prepatory period of accumulating data, followed by some essential but unforeseeable transformation. William James remarked in the same vein that we learn to swim in winter and skate in summer. We learn that which we do not concentrate on, the part that has been exercised and trained in the past but that is now lying fallow. Not doing can sometimes be more productive than doing.

Stephen Nachmanovitch in Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art

Comments are welcome!

Q: This portrait has an interesting story. Can you explain? (Question from Anna Rybat via Facebook)

A: “John” was one of several portraits I made of friends in 1988-90 to build up my portfolio for the portrait company I worked for when I left the active duty Navy. I had gifted it to John Breeskin, the psychologist/friend pictured.

When he died, someone sent it back to me. (I hadn’t known he died). I must have not been working that day so for some reason, it was delivered to a print studio on another floor in my building. When the printer moved out, he found it and got in touch with me. By that time he had had “John” for more than a year and never bothered to tell me! The packaging had been removed so I have no idea who sent it or where exactly it came from.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 555

Studio view showing some tools of the trade

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Rembrandt and Shakespeare, Tolstoy and Gauguin, possessed, I believe, powerful hearts, not powerful wills. They loved the range of material they used, the work’s possibilities excited them; the field’s complexities fired their imaginations. The caring suggested the tasks; the tasks suggested the schedules. They learned their fields and then loved them. They worked, respectfully, out of their love and knowledge, and they produced complex bodies of work that endure. Then, and only then, the world maybe flapped at them

some sort of hat, which, if they were still living, they ignored as well as they could, to keep at their tasks.

Annie Dillard in The Abundance, quoted in The Marginalian by Maria Popova, November 23, 2022

Comments are welcome!

Q: It must be tricky moving pastel paintings from your New York studio to your framer in Virginia. Can you explain what’s involved? (Question from Ni Zhu via Instagram)

“Impresario” partially boxed for transport to Virginia

A: Well, I have been working with the same framer for three decades so I am used to the process.

Once my photographer photographs a finished, unframed piece, I carefully remove it from the 60” x 40” piece of foam core to which it has been attached (with bulldog clips) during the months I worked on it. I carefully slide the painting into a large covered box for transport. Sometimes I photograph it in the box before I put the cover on (see above).

My studio is in a busy part of Manhattan where only commercial vehicles are allowed to park, except on Sundays. Early on a Sunday morning, I pick up my 1993 Ford F-150 truck from Pier 40 (a parking garage on the Hudson River at the end of Houston Street) and drive to my building’s freight elevator. I try to park relatively close by. On Sundays the gate to the freight elevator is closed and locked so I enter the building around the corner via the main entrance. I unlock my studio, retrieve the boxed painting, bring it to the freight elevator, and buzz for the operator. He answers and I bring the painting down to my truck. Then I load it into the back of my truck for transport to my apartment.

I drive downtown to the West Village, where I live, and double park my truck. (It’s generally impossible to park on my block). I hurry to unload the painting, bring it into my building, and up to my apartment, all the while hoping I do not get a parking ticket. The painting will be stored in my apartment, away from extreme cold or heat, until I’m ready to drive to Virginia. On the day I go to Virginia, I load it back into my truck. Then I make the roughly 5-hour drive south.

Who ever said being an artist is easy was lying!

Comments are welcome!

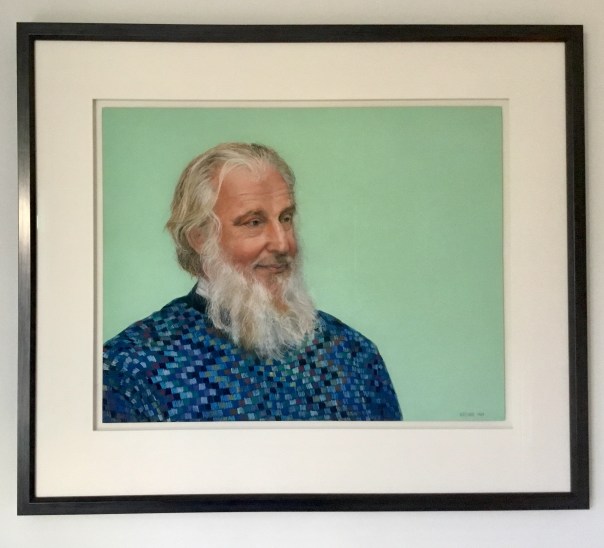

Q: How do you account for your intense compositions? (Question from Robin Plati via Facebook)

A: If I do say so, composition is something I’m known for. During the months I work on them, I devote many hours to looking at the painting on my easel and figuring out how to move the viewer’s eyes around in interesting ways. Everything you see is carefully worked out after hundreds of studio hours. Finished pastel paintings always have an inevitability about them. Change one detail and the entire composition is thrown off.

Comments are welcome!

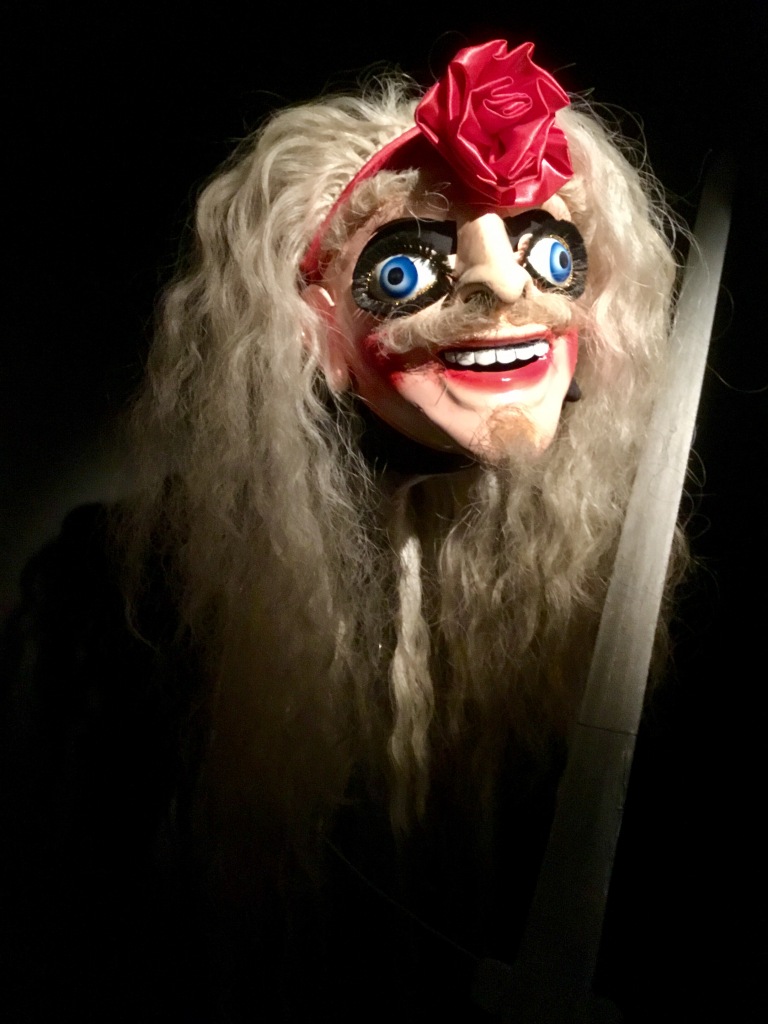

Q: What art project(s) are you working on currently? What is your inspiration or motivation for this? (Question from artamour)

A: While traveling in Bolivia in 2017, I visited a mask exhibition at the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz. The masks were presented against black walls, spot-lit, and looked eerily like 3D versions of my Black Paintings, the series I was working on at the time. I immediately knew I had stumbled upon a gift. To date I have completed seventeen pastel paintings in the Bolivianos series. One awaits finishing touches, another is in progress, and I am planning the next two, one large and one small pastel painting.

The following text is from my “Bolivianos” artist’s statement.

“My long-standing fascination with traditional masks took a leap forward in the spring of 2017 when I visited the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, Bolivia. One particular exhibition on view, with more than fifty festival masks, was completely spell-binding.

The masks were old and had been crafted in Oruro, a former tin-mining center about 140 miles south of La Paz on the cold Altiplano (elevation 12,000’). Depicting important figures from Bolivian folklore traditions, the masks were created for use in Carnival celebrations that happen each year in late February or early March.

Carnival in Oruro revolves around three great dances. The dance of “The Incas” records the conquest and death of Atahualpa, the Inca emperor when the Spanish arrived in 1532. “The Morenada” dance was once assumed to represent black slaves who worked in the mines, but the truth is more complicated (and uncertain) since only mitayo Indians were permitted to do this work. The dance of “The Diablada” depicts Saint Michael fighting against Lucifer and the seven deadly sins. The latter were originally disguised in seven different masks derived from medieval Christian symbols and mostly devoid of pre-Columbian elements (except for totemic animals that became attached to Christianity after the Conquest). Typically, in these dances the cock represents Pride, the dog Envy, the pig Greed, the female devil Lust, etc.

The exhibition in La Paz was stunning and dramatic. Each mask was meticulously installed against a dark black wall and strategically spotlighted so that it became alive. The whole effect was uncanny. The masks looked like 3D versions of my “Black Paintings,” a pastel paintings series I have been creating for ten years. This experience was a gift… I could hardly believe my good fortune!

Knowing I was looking at the birth of a new series – I said as much to my companions as I remained behind while they explored other parts of the museum – I spent considerable time composing photographs. Consequently, I have enough reference material to create new pastel paintings in the studio for several years. The series, entitled “Bolivianos,” is arguably my strongest and most striking work to date.”

Comments are welcome!