Blog Archives

Q: You take 3-4 months to complete one artwork. How do you plan a series such as Bolivianos over a year’s timeline and over the years? (Question from Vedica Art Studios and Gallery)

A: Bolivianos is my third series, and like the previous two, it naturally evolves from one painting to the next. There wasn’t a long-term plan involved, and I doubt such detailed planning would even be practical. Many artists likely work this way—finishing one project and then beginning another. As with Bolivianos, I typically have ideas for the next two or three paintings, but little concept beyond that.

The main impetus for Bolivianos was to continue work I began in the early 1990s. During a visit to La Paz, I captured a series of stunning photographs, inspiring me to translate them into a major pastel series. Each painting leads to ideas about the next, guiding the entire series’ evolution and shaping my understanding of its meaning. Both the series and my insights deepen as I engage further with the subject matter. The Bolivian Carnival masks I photographed provided the starting point for a long and continuing intellectual journey.

Comments are welcome!

Q: What art project(s) are you working on currently? What is your inspiration or motivation for this? (Question from artamour)

A: While traveling in Bolivia in 2017, I visited a mask exhibition at the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz. The masks were presented against black walls, spot-lit, and looked eerily like 3D versions of my Black Paintings, the series I was working on at the time. I immediately knew I had stumbled upon a gift. To date I have completed seventeen pastel paintings in the Bolivianos series. One awaits finishing touches, another is in progress, and I am planning the next two, one large and one small pastel painting.

The following text is from my “Bolivianos” artist’s statement.

“My long-standing fascination with traditional masks took a leap forward in the spring of 2017 when I visited the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, Bolivia. One particular exhibition on view, with more than fifty festival masks, was completely spell-binding.

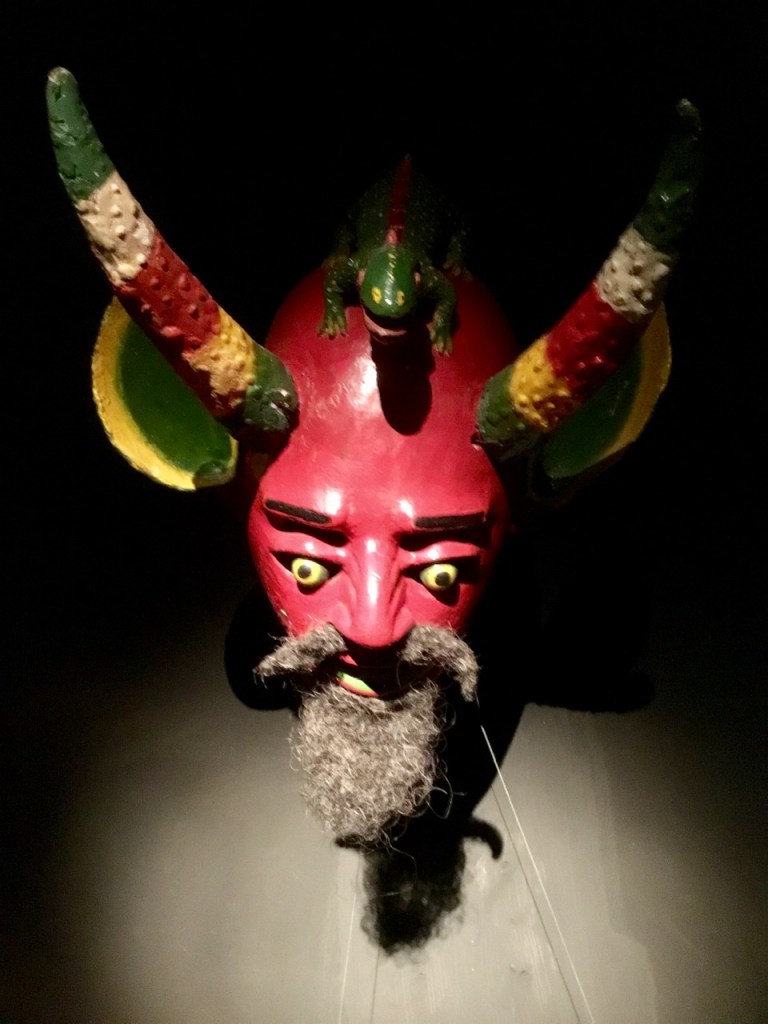

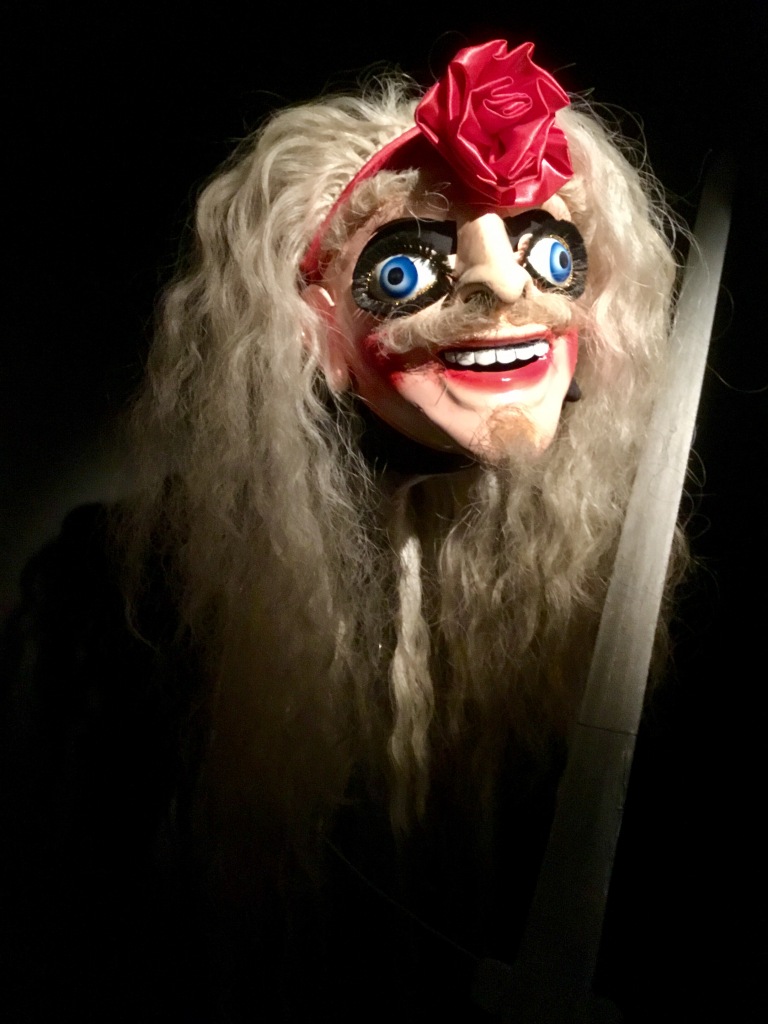

The masks were old and had been crafted in Oruro, a former tin-mining center about 140 miles south of La Paz on the cold Altiplano (elevation 12,000’). Depicting important figures from Bolivian folklore traditions, the masks were created for use in Carnival celebrations that happen each year in late February or early March.

Carnival in Oruro revolves around three great dances. The dance of “The Incas” records the conquest and death of Atahualpa, the Inca emperor when the Spanish arrived in 1532. “The Morenada” dance was once assumed to represent black slaves who worked in the mines, but the truth is more complicated (and uncertain) since only mitayo Indians were permitted to do this work. The dance of “The Diablada” depicts Saint Michael fighting against Lucifer and the seven deadly sins. The latter were originally disguised in seven different masks derived from medieval Christian symbols and mostly devoid of pre-Columbian elements (except for totemic animals that became attached to Christianity after the Conquest). Typically, in these dances the cock represents Pride, the dog Envy, the pig Greed, the female devil Lust, etc.

The exhibition in La Paz was stunning and dramatic. Each mask was meticulously installed against a dark black wall and strategically spotlighted so that it became alive. The whole effect was uncanny. The masks looked like 3D versions of my “Black Paintings,” a pastel paintings series I have been creating for ten years. This experience was a gift… I could hardly believe my good fortune!

Knowing I was looking at the birth of a new series – I said as much to my companions as I remained behind while they explored other parts of the museum – I spent considerable time composing photographs. Consequently, I have enough reference material to create new pastel paintings in the studio for several years. The series, entitled “Bolivianos,” is arguably my strongest and most striking work to date.”

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 482

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Devils’ heads with daring and disturbing eyes, twisted horns, abundant grey hair and hooked noses hang on the blue walls of Antonio Viscarra’s house. Long benches covered with old, multi-colored cushions in Bolivian motifs surround the concrete floor of the small room. Several dozen of these hanging faces, which seem to watch in silence from the darkness, are ready to be used in festivals and traditional dances.

The maskmaker or “maestro” as he is called, lives [deceased now] in the area of Avenida Buenos Aires, far from the political and administrative center of the city of La Paz, but rather at the very center of the other La Paz (Chuquiago in the Aymara language) where many peasant immigrants have settled, and which for that reason, is the center of the city’s popular culture.

Viscarra is the oldest creator of masks in La Paz, and his work has helped to conserve, and at the same time to rejuvenate, the tradition of using masks in Bolivian dances. If economic progress and alienation have contributed to the excessive adornment of new masks with glass and other foreign materials, Viscarra, in an attempt to recover the distinctive, original forms, has gone back to the 100-year-old molds used by his grandfather. His work has been exhibited in Europe, in the United States and in South America, Most important, however, is that Viscarra is transmitting his knowledge to his children, ensuring that this form of authentic Bolivian culture will never die.

…Viscarra inherited the old mask molds from his grandfather and was told to take good care of them because some day he might need them. After keeping them carefully put away for 50 years, the maestro used them again for an exhibition of masks prepared in 1984, slowly recreating the original masks, beautiful in their simplicity, in their delicate craftsmanship and in their cultural value. In this way, the masks which emerged from the old molds are regaining their past prestige and importance.

Antonio Viscarra, The mask Maker by Wendy McFarren in Masks of the Bolivian Andes, Editorial Quipus and Banco Mercantil

Comments are welcome!

Q: What are your favorite subject(s) and media? (Question from “Arts Illustrated”)

A: Here’s the short answer. I work exclusively in soft pastel on sandpaper, using self-invented pastel techniques that I have been refining for thirty-five years. Since 2017, I have depicted authentic Bolivian Carnival masks that I encountered and photographed at the Museum of Ethnography and Folklore In La Paz.

Comments are welcome!