Blog Archives

Q: Can you explain how your current work relates to Jungian archetypes?

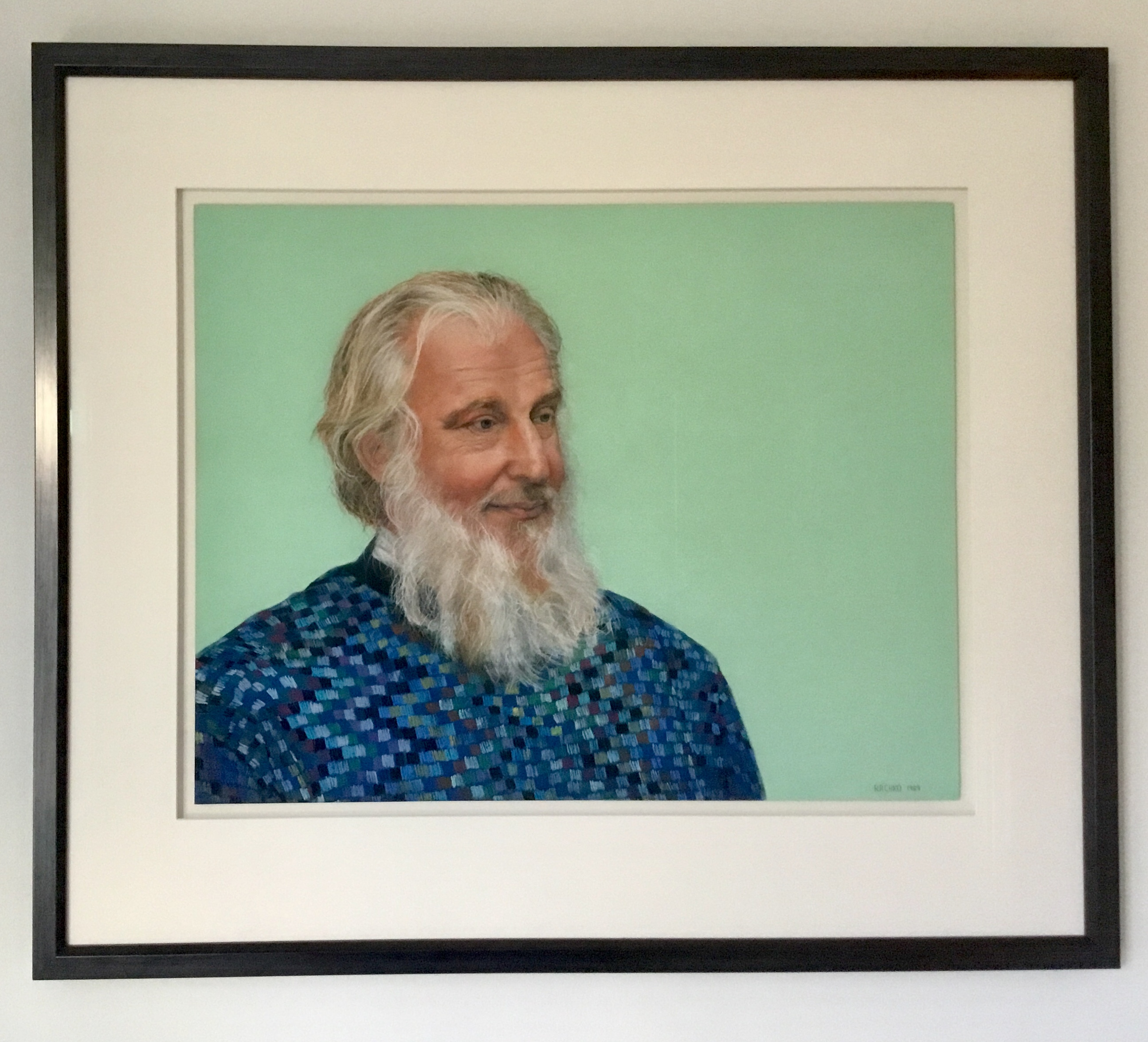

In progress: “Wise One,” soft pastel on sandpaper, 58” x 38”

A: Here’s an example. The passage below is from Carl Jung: Knowledge in a Nutshell by Gary Bobroff.

The Wise Old Man or Woman is a figure found throughout folklore and mythology. They possess superior understanding and also often a more developed spiritual or moral character. Frequently, such characters provide the information or learning that the Hero needs to move forward in their quest. In Star Wars, Ben Kenobi plays the teacher to Luke, introducing purpose and knowledge into the young Hero’s life. Where the Hero brings drive, courage, and direct action, the Wise Old One introduces the importance of the opposing values of thought and questioning. Jung describes it thus: ‘Often the old man in fairytales asks questions like who? Why? Whence? Wither? For the purpose of inducing self-reflection and mobilizing the moral forces.’

The Wise One may appear in disguise to test the character of others. In the second Star Wars film, The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Luke’s mentor Yoda does not reveal himself as such when they first meet. He waits, asking questions that test Luke’s motivation for being there. Jung associated the Trickster archetype with the Wise One, and the use of disguise emphasizes this correlation.

Comments are welcome!

Q: How has the use of photography in your work changed over the decades?

New York, NY

A: From the beginning in the mid-1980s I used photographs as reference material. My late husband, Bryan, would shoot 4” x 5” negatives of my elaborate setups using his Toyo-Omega view camera. In this respect Bryan was an integral part of my creative process as I developed the “Domestic Threats” pastel paintings. At that time I rarely picked up a camera, except to capture memories of our travels.

After Bryan was killed on 9/11, I inherited his extensive camera collection – old Nikons, Leicas, Graphlex cameras, and more. I wanted and needed to learn how to use them. Starting in 2002 I enrolled in a series of photography courses (about 10 over 4 years) at the International Center of Photography in New York. I learned how to use all of Bryan’s cameras and how to make my own big chromogenic prints in the darkroom.

Along the way I discovered that the sense of composition and color I had developed over many years as a painter translated well into photography. The camera was just another medium with which to express my ideas. Surprisingly, in 2009 I had my first solo photography exhibition at a gallery in New York. Bryan would have been so proud!

For several years now my camera of choice has been a 12.9” iPad Pro. It’s main advantage is that the large screen let’s me see every detail as I compose my photographs. I think of it as a portable, lightweight, and easy-to-use 8 x 10 view camera. My iPad is always with me when I travel and as I walk around exploring New York City.

It is a wonderful thing to be both a painter and a photographer! While pastel painting will always be my first love, photography has distinct advantages over my studio practice. Pastel paintings are labor-intensive, requiring months of painstaking work. Photography’s main advantage is speed. Photographs – from the initial impulse to hanging a print on a wall – can be made in minutes. Photography is instant gratification, allowing me to explore ideas much easier and faster than I ever could as a painter. Perhaps most importantly, composing photographs keeps my eye sharp whenever I am away from the studio. I credit photography as an important factor in the overall evolution of my work.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 540

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The Wise Old Man or Woman is a figure found throughout folklore and mythology. They possess superior understanding and also often a more developed spiritual or moral character. Frequently, such characters provide the information or learning that the Hero needs to move forward in their quest. In “Star Wars,” Ben Kenobi plays the teacher to Luke, introducing purpose and knowledge into the young Hero’s life. Where the Hero brings a drive, courage, and direct action, the Wise Old One introduces the importance of the opposing values of thought and questioning. Jung describes it thus: ‘Often the old man in fairytales asks questions like who? Why? Whence? Wither? For the purpose of inducing self-reflection and mobilizing the moral force.’

The Wise One may appear in disguise to test the character of others. In the second “Star Wars” film, “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980), Luke’s mentor Yoda does not reveal himself as such when they first meet. He waits, asking questions that test Luke’s motivation for being there. Jung associated the Trickster archetype with the Wise One, and the use of disguise emphasizes this correlation.

Gary Bobroff in Carl Jung: Knowledge in a Nutshell

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 468

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Why does art elicit such different reactions from us? How can a work that bowls one person over leave another cold? Doesn’t the variability of the aesthetic feeling support the view that art is culturally determined and relative? Maybe not, if we consider the possibility that the artistic experience depends not on some subjective mood but on an individually acquired (hence variable) power to be affected by art, a capacity developed through one’s culture in tandem with one’s unique character. For evidence of this we can point to works that seem to ignore cultural boundaries altogether, affecting people of different backgrounds in comparable ways even though a specific articulation of their personal responses continues to vary. Consider the plays of William Shakespeare or Greek theater, or the fairy tales that have sprung up in similar forms on every continent. We could not be further removed from the people who painted in the Chauvet Cave, nor could we be more oblivious as to the significance they ascribed to their pictures. Yet their work affects us across the millennia. Everyone responds to them differently, of course, and the spirit in which people are likely to receive them now probably differs significantly from how it was at the beginning. But these permutations revolve around a solid core, something present in the images themselves.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Q: How has photography changed your approach to painting?

A: Except for many hours spent in life-drawing classes and still life setups that I devised when I was learning my craft in the 1980s, I have always worked from photographs. My late husband, Bryan, would shoot 4” x 5” negatives of my elaborate “Domestic Threats” setups using his Toyo-Omega view camera. I rarely picked up a camera except when we were traveling. After Bryan was killed on 9/11, I inherited his extensive (film) camera collection – old Nikons, Leicas, Graphlex cameras, etc. – and needed to learn how to use them. Starting in 2002 I enrolled in a series of photography courses (about 10 over 4 years) at the International Center of Photography in New York. I learned how to use all of Bryan’s cameras and how to make my own big color prints in the darkroom.

Early on I discovered that the sense of composition, color, and form I had developed over many years as a painter translated well into photography. The camera was, and is, just another medium with which to express ideas. Pastel painting will always be my first love. However, pastel paintings take months of work, while photography offers instant gratification, especially with my current preferred camera, an iPad Pro.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 438

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Although {Manuel} Alvarez Bravo and Cartier-Bresson were both important mentors for Iturbide, her photographs, as she confirms, are not connected to Surrealism in any way. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s publication Carnets du Mexique (Mexican Notebooks) was an important influence, as it presented a visual representation of Mexico that resonated with her. (Cartier-Bresson also worked mainly in Juchitan, where Iturbide has spent a great deal of time). However, Iturbide developed a way of working quite different from Cartier-Bresson’s. What distinguishes the two artists’ photographs lies in the notion of the fleeting instant, or, as Cartier-Bresson called it, “the decisive moment.” Iturbide refers to Cartier-Bresson’s interest in the “sharp eye” and capturing an instant in time, and describes her own intentions when photographing: “More than in time, I’m interested in the artistic form of the symbol.” Further, Iturbide’s photographs are taken with an understanding of the people, rituals, and symbols of the communities she captures, which makes them stand apart from Cartier-Bresson’s fleeting moments of Mexico. Her work is informed by her deep connection and empathy for her subjects.

Kristen Gresh in Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 380

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The freedom he enjoyed came at a cost. But those fears and irritations evaporated amid the support the artists gave one another immediately after the war. A community developed that sustained them and gave them courage. “You have to have confidence amounting to arrogance, because particularly at the beginning, you’re making something that nobody asked you to make,” Elaine [de Kooning] said. “And you have to have total confidence in yourself, and in the necessity of what you’re doing.” That was much easier done in a group of like-minded individuals.

Mary Gabriel in Ninth Street Women

Comments are welcome!