Category Archives: Source Material

Q: What inspires you to start your next painting? (Question from Nancy Nikkal)

A: For my current series, “Bolivianos,” I am using as source/reference material c-prints composed at a La Paz museum in 2017. I began the series by picking my favorite from this group of photos (“The Champ” and later, “Avenger”) before continuing with others selected for prosaic reasons such as I like some aspect of the photo, to push my technical skills by figuring out how to render some item in pastel, to challenge myself to make a pastel painting that is more exciting than the photo, etc. I like to think I have mostly succeeded.

At this time I am running low on images and have not yet imagined what comes next. Do I travel to La Paz again in 2021 to capture new photos? This series was a surprise gift so I am reluctant to deliberately chase after it knowing that ‘lightning never strikes twice.’ Will travel even be possible this year with Covid-19? These are questions I am wrestling with now.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 428

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

In its spectacle and ritual the Carnival procession in Oururo bears an intriguing resemblance to the description given by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega of the great Inca festival of Inti Raymi, dedicated to the Sun. Even if Oururo’s festival did not develop directly from that of the Inca, the 16th-century text offers a perspective from the Andean tradition:

“The curacas (high dignitaries) came to their ceremony in their finest array, with garments and head-dresses richly ornamented with gold and silver.

Others, who claimed to descend from a lion, appeared, like Hercules himself, wearing the skin of this animal, including its head.

Others, still, came dressed as one imagines angels with the great wings of the bird called condor, which they considered to be their original ancestor. This bird is black and white in color, so large that the span of its wing can attain 14 or 15 feet, and so strong that many a Spaniard met death in contest with it.

Others wore masks that gave them the most horrible faces imaginable, and these were he Yuncas (people from the tropics), who came to the feast with the heads and gestures of madmen or idiots. To complete the picture, they carried appropriate instruments such as out-of-tune flutes and drums, with which they accompanied the antics.

Other curacas in the region came as well decorated or made up to symbolize their armorial bearings. Each nation presented its weapons: bows and arrows, lances, darts, slings, maces and hatchets, both short and long, depending upon whether they used them with one hand or two.

They also carried paintings, representing feats they had accomplished in the service of the Sun and of the Inca, and a whole retinue of musicians played on the timpani and trumpets they had brought with them. In other words, it may be said that each nation came to the feast with everything that could serve to enhance its renown and distinction, and if possible, its precedence over the others.”

El Carnaval de Oruro by Manuel Vargas in Mascaras de los Andes Bolivianos, Editorial Quipus and Banco Mercantil

Comments are welcome!

Q: Can you briefly explain how the Bolivian Carnival masks you depict in your work are used?

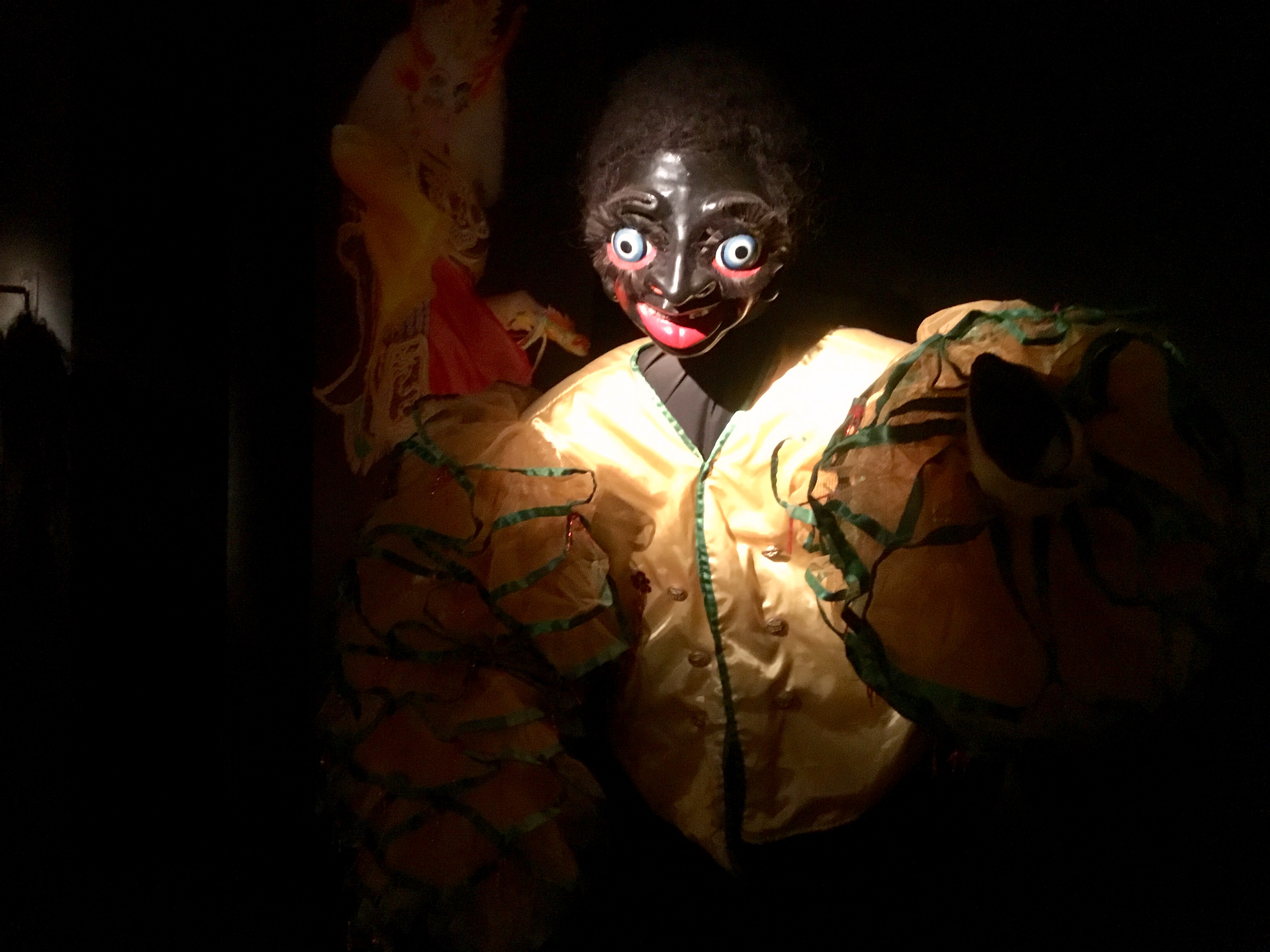

A: The masks depict important figures from Bolivian folklore traditions and are used in Carnival celebrations in the town of Oruro. Carnival occurs every year in late February or early March. I had hoped to visit again this year, but political instability in Bolivia made a trip too risky.

Carnival in Oruro revolves around three great dances. The dance of “The Incas” records the conquest and death of Atahualpa, the Inca emperor when the Spanish arrived in 1532. “The Morenada” music and dance style from the Bolivian Andes was possibly inspired by the suffering of African slaves brought to work in the silver mines of Potosi. The dance of “The Diablada” depicts Saint Michael fighting against Lucifer and the seven deadly sins. Lucifer was disguised in seven different masks derived from medieval Christian symbols aor totemic animals that became nd mostly devoid of pre-Columbian elements (except that became attached to Christianity after the Conquest). Typically, in these dances the cock represents Pride, the dog Envy, the pig Greed, the female devil Lust, etc.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 385

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Sunday of Carnival, the parade begins. For a whole day of celebration in music and dance, people can express their hope and fears, revive their myths and escape to a reality far from everyday life.

Thousands of spectators arrive from different parts if Bolivia and other countries. Filling the streets, they straddle benches, window ledges, balconies, cats and eve hang from walls or roofs to witness the entrance of the Carnival. Thus is the magnificent parade when Carnival makes its official entry into Oruro. The comparsas (dance troupes) dance to music for20 blocks, nearly eight lies, to the Church of the Virgin of Socavón (Virgin of the Mine). Each tries to out do the next in the brilliance of their costumes, the energy of their dancing and the power of their music. All their efforts are dedicated to the Virgin whose shrine is found on the hill called Pie de Gallo.

If there are thousands of spectators, there are also thousands of dancers from the city and other parts of the country. Among the most remarkable are the Diablos and Morenos which count for eight of the 40 or 50 participating groups. Keeping in mind that the smallest troupes have between 30 and 50 embers and the largest between 200 and 300, it is possible to calculate the number of dancers and imagine the spectacle.

… Each dance recalls a particular aspect of life in the Andes. Lifted from different periods and places, the dances offer a rich interpretation of historical events, creating an imaginative mythology for Oruro.

… Carnival blends indigenous beliefs and rituals with those introduced by the Spaniards. Both systems of belief have undergone transformations, each making allowance for the other, either through necessity or familiarity. The Christianity fought from Europe becomes loaded with new meanings while the myths and customs of the Andes accommodate their language and creativity to the reality of their conquered world. The process can be seen as a struggle culminating in a ‘mestizaje’ or new cultural mix.

El Carnaval de Oruro by Manuel Vargas in Mascaras de los Andes Bolivianos, Editorial Quipus and Banco Mercantil

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 373

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

“I need to be inspired by my own work,” he said. “There’s no point in being inspired by Picasso. It’s OK, but it doesn’t help you. If you’re an artist you have to thrive on what you do and believe in what you do and be obsessed by it.”

Roger Ballens quoted in A Puzzle with No Solution: Roger Ballen’s Quest for Meaning Through Photography, by Jordan G. Teicher, New York Times, April 24, 2018.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Your work is unlike anyone else’s. There is such power and boldness in your pastels. What processes are you using to create such poignant and robustly colored work?

A: For thirty-three years I have worked exclusively in soft pastel on sandpaper. Pastel, which is pigment and a binder to hold it together, is as close to unadulterated color as an artist can get. It allows for very saturated color, especially using the self-invented techniques I have developed and mastered. I believe my “science of color” is unique, completely unlike how any other artist works. I spend three to four months on each painting, applying pastel and blending the layers together to mix new colors on the paper.

The acid-free sandpaper support allows the buildup of 25 to 30 layers of pastel as I slowly and meticulously work for hundreds of hours to complete a painting. The paper is extremely forgiving. I can change my mind, correct, refine, etc. as much as I want until a painting is the best I can create at that moment in time.

My techniques for using soft pastel achieve rich velvety textures and exceptionally vibrant color. Blending with my fingers, I painstakingly apply dozens of layers of pastel onto the sandpaper. In addition to the thousands of pastels that I have to choose from, I make new colors directly on the paper. Regardless of size, each pastel painting takes about four months and hundreds of hours to complete.

I have been devoted to soft pastel from the beginning. In my blog and in numerous interviews online and elsewhere, I continue to expound on its merits. For me no other fine art medium comes close.

My subject matter is singular. I am drawn to Mexican, Guatemalan, and Bolivian cultural objects—masks, carved wooden animals, papier mâché figures, and toys. On trips to these countries and elsewhere I frequent local mask shops, markets, and bazaars searching for the figures that will populate my pastel paintings. How, why, when, and where these objects come into my life is an important part of the creative process. Each pastel painting is a highly personal blend of reality, fantasy, and autobiography.

Comments are welcome!

Q: When did your love of indigenous artifacts begin? Where have you traveled to collect these focal points of your works and what have those experiences taught you?

A: As a Christmas present in 1991 my future sister-in-law sent me two brightly painted wooden animal figures from Oaxaca, Mexico. One was a blue polka-dotted winged horse. The other was a red, white, and black bear-like figure.

I was enthralled with this gift and the timing was fortuitous because I had been searching for new subject matter to paint. I started asking artist-friends about Oaxaca and learned that it was an important art hub. Two well-known Mexican painters, Rufino Tamayo and Francisco Toledo, had gotten their start there, as had master photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo. There was a “Oaxacan School of Painting” (‘school’ meaning a style) and Alvarez Bravo had established a photography school there (the building/institution kind). I began reading everything I could find. At the time I had only been to Mexico very briefly, in 1975.

The following autumn, Bryan and I planned a two-week trip to visit Mexico. We timed it to see Day of the Dead celebrations in Oaxaca. (During my research I had become fascinated with this festival). We spent one week in Oaxaca followed by one week in Mexico City. My interest in collecting Mexican folk art was off and running!

Along with busloads of other tourists, we visited several cemeteries in small Oaxacan towns for the “Day of the Dead.” The indigenous people tending their ancestors’ graves were so dignified and so gracious, even with so many mostly-American tourists tromping around on a sacred night, that I couldn’t help being taken with these beautiful people and their beliefs.

From Oaxaca we traveled to Mexico City, where again I was entranced, but this time by the rich and ancient history. We visited the National Museum of Anthropology, where I was introduced to the fascinating story of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations; the ancient city of Teotihuacan, which the Aztecs discovered as an abandoned city and then occupied as their own; and the Templo Mayor, the historic center of the Aztec empire, infamous as a place of human sacrifice. I was astounded! Why had I never learned in school about Mexico, this highly developed cradle of Western civilization in our own hemisphere, when so much time had been devoted to the cultures of Egypt, Greece, and elsewhere? When I returned home to Virginia I began reading everything I could find about ancient Mexican civilizations, including the Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Aztec, and Maya. The first trip to Mexico opened up a whole new world and was to profoundly influence my future work. I would return there many more times, most recently to study Olmec art and archeology. In subsequent years I have traveled to Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia and other countries in search of inspiration and subject matter to depict in my work.

Comments are welcome!