Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 650

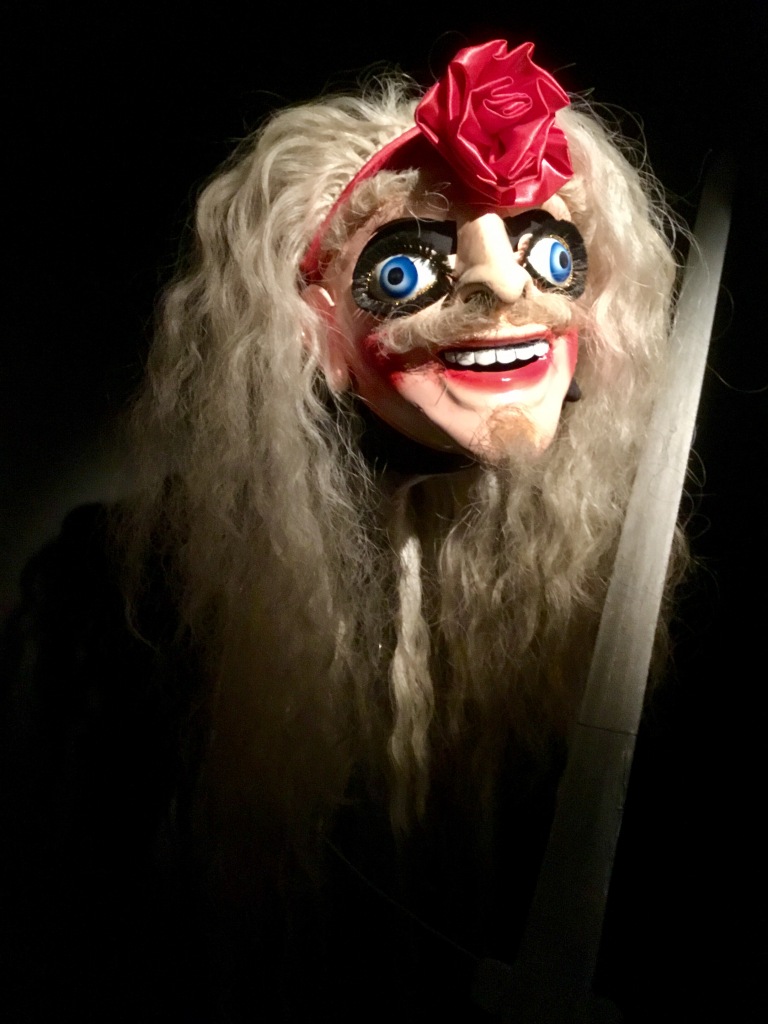

Some of Barbara’s Mexican and Guatemalan folk art collection

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Art objects are not just gifts for the viewer: they can hold profound, even mystical, revelations for the maker. When actualizing work that comes from your core, one of the greatest sources of pleasure is the recording of your art life journey, with the serendipitous connections, the seminal players, and meaningful symbols that return again and again. Art is an unconscious language that knows more about you than you know about yourself.

Kate Kretz in Art From Your Core: A Holistic Guide to Visual Voice

Comments are welcome!

Q: What art project(s) are you working on currently? What is your inspiration or motivation for this? (Question from artamour)

A: While traveling in Bolivia in 2017, I visited a mask exhibition at the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz. The masks were presented against black walls, spot-lit, and looked eerily like 3D versions of my Black Paintings, the series I was working on at the time. I immediately knew I had stumbled upon a gift. To date I have completed seventeen pastel paintings in the Bolivianos series. One awaits finishing touches, another is in progress, and I am planning the next two, one large and one small pastel painting.

The following text is from my “Bolivianos” artist’s statement.

“My long-standing fascination with traditional masks took a leap forward in the spring of 2017 when I visited the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, Bolivia. One particular exhibition on view, with more than fifty festival masks, was completely spell-binding.

The masks were old and had been crafted in Oruro, a former tin-mining center about 140 miles south of La Paz on the cold Altiplano (elevation 12,000’). Depicting important figures from Bolivian folklore traditions, the masks were created for use in Carnival celebrations that happen each year in late February or early March.

Carnival in Oruro revolves around three great dances. The dance of “The Incas” records the conquest and death of Atahualpa, the Inca emperor when the Spanish arrived in 1532. “The Morenada” dance was once assumed to represent black slaves who worked in the mines, but the truth is more complicated (and uncertain) since only mitayo Indians were permitted to do this work. The dance of “The Diablada” depicts Saint Michael fighting against Lucifer and the seven deadly sins. The latter were originally disguised in seven different masks derived from medieval Christian symbols and mostly devoid of pre-Columbian elements (except for totemic animals that became attached to Christianity after the Conquest). Typically, in these dances the cock represents Pride, the dog Envy, the pig Greed, the female devil Lust, etc.

The exhibition in La Paz was stunning and dramatic. Each mask was meticulously installed against a dark black wall and strategically spotlighted so that it became alive. The whole effect was uncanny. The masks looked like 3D versions of my “Black Paintings,” a pastel paintings series I have been creating for ten years. This experience was a gift… I could hardly believe my good fortune!

Knowing I was looking at the birth of a new series – I said as much to my companions as I remained behind while they explored other parts of the museum – I spent considerable time composing photographs. Consequently, I have enough reference material to create new pastel paintings in the studio for several years. The series, entitled “Bolivianos,” is arguably my strongest and most striking work to date.”

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 406

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

If we really are due for a shift in consciousness, it is incumbent upon each of us to “be the change,” in Gandhi’s famous phrase. Nothing is written in the stars.

Art is a testament to this way of thinking, because every great work of art is made, not for an abstract audience, but for the lone percipient with whom it seeks to connect. The symbols that compose artistic works are not static objects but dynamic events. As such, they can only emerge within a field of awareness, that is, within the context of a life being lived. It is therefore by approaching the work of art as though it were intended specifically for you – as though the artist had fashioned it with you in mind every step of the way – that you can turn the aesthetic experience into an engine of change in your own life and in the lives of those around you.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Q: Can you briefly explain how the Bolivian Carnival masks you depict in your work are used?

A: The masks depict important figures from Bolivian folklore traditions and are used in Carnival celebrations in the town of Oruro. Carnival occurs every year in late February or early March. I had hoped to visit again this year, but political instability in Bolivia made a trip too risky.

Carnival in Oruro revolves around three great dances. The dance of “The Incas” records the conquest and death of Atahualpa, the Inca emperor when the Spanish arrived in 1532. “The Morenada” music and dance style from the Bolivian Andes was possibly inspired by the suffering of African slaves brought to work in the silver mines of Potosi. The dance of “The Diablada” depicts Saint Michael fighting against Lucifer and the seven deadly sins. Lucifer was disguised in seven different masks derived from medieval Christian symbols aor totemic animals that became nd mostly devoid of pre-Columbian elements (except that became attached to Christianity after the Conquest). Typically, in these dances the cock represents Pride, the dog Envy, the pig Greed, the female devil Lust, etc.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 368

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Whether we look to the contradictory functions that people are asked to fulfill today – devoted parent and loyal employee, faithful spouse and emancipated libertine, mature adult and eternal child – or to the ways in which identities are disbursed across divergent political forums, information systems, and communication networks, the same observation holds: we are infinitely divided. What is called an individual today is an abstract assemblage of fragments. Phone calls, emails, voice mails, blogs, videos and photos, surveillance tapes, banking records: the body is dwarfed by the virtual tendrils that shoot out if it through time and space, any of which is likely to claim to be the real “you” as you are. Only the imaginal mind can lead us out of the maze, with art providing the symbols that mark the way to the elusive essence that truly defines us.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice:A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 324

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

“The artist is the creator of beautiful things.” From [Immanuel] Kant’s perspective on conventional beauty, [Oscar] Wilde’s definition would seem to demote artists to a cosmetic role, turning them, as William Irwin Thompson said, into “the interior decorators of Plato’s cave.” On the other hand, under the terms of a radical beauty that brings forth the Real instead of pacifying us with delusions of “realism,” Wilde’s line can help restore art to its shamanic source in our minds. Perhaps it would have been better if Wilde had defined the artist as the creator of numinous things – of enchanted objects, omens, or talismans. Because if there is one thing that all beautiful things share, it is that they are all symbols. They are all transmissions from another plane of existence.

It is one thing to acknowledge the Beautiful as an objective property of the phenomenal world. It is another to stop and listen to what it has to say.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Q: What significance do the folk art figures that you collect during your travels have for you?

A: I am drawn to each figure because it possesses a powerful presence that resonates with me. I am not sure exactly how or why, but I know each piece I collect has lessons to teach.

Who made this thing? How? Why? Where? When? I feel connected to each object’s creator and curiosity leads me to become a detective and an archaeologist to find out more about them and to figure out how to best use them in my work.

The best way I can describe it: after nearly three decades of seeking out, collecting, and using these folk art figures as symbols in my work, the entire process has become a rich personal journey towards gaining greater knowledge and wisdom.

Comments are welcome!