Blog Archives

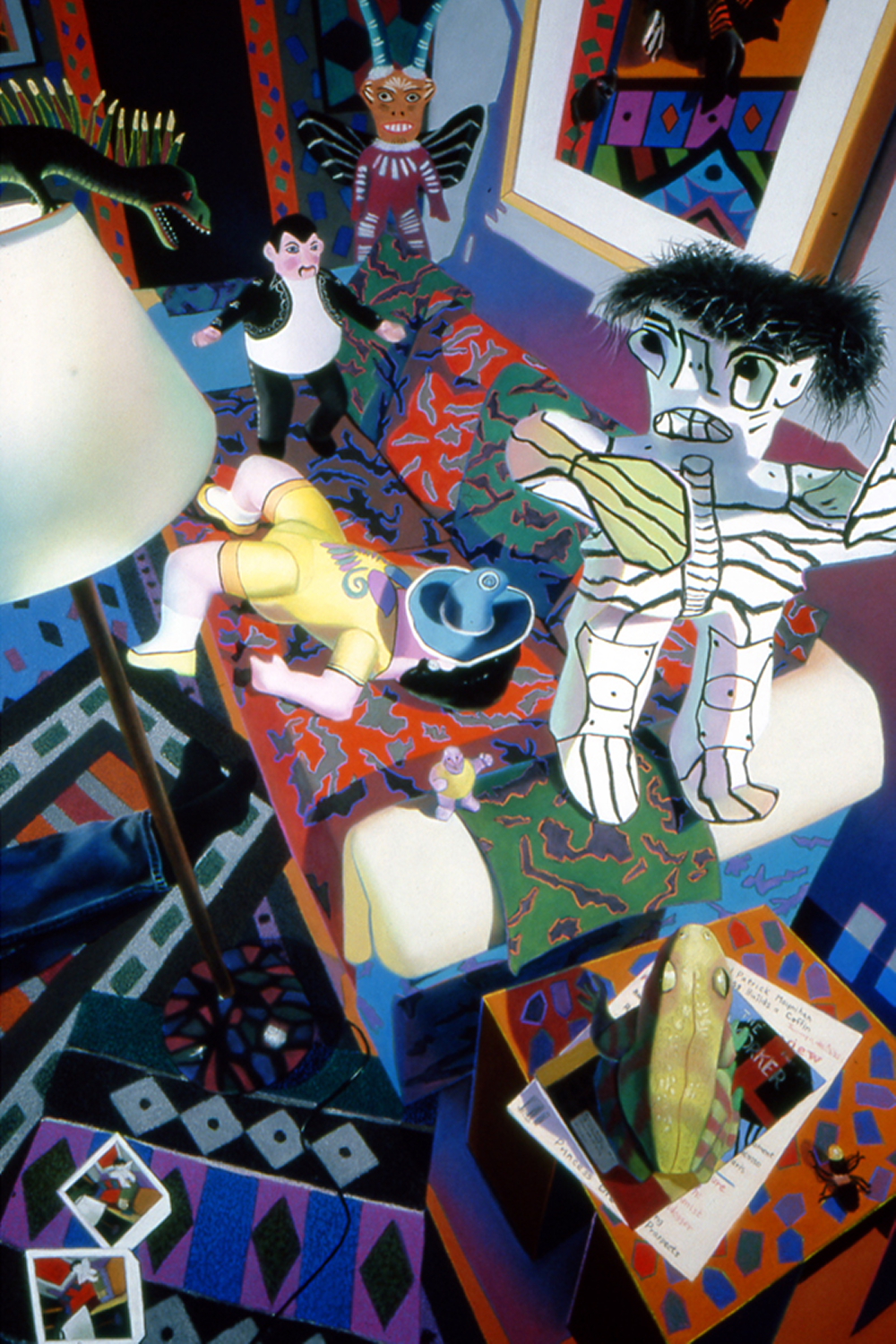

Q: How large is your collection of Mexican folk art objects?

Part of my collection

A: I began collecting these figures in the early 1990s. I haven’t counted them, but my guess is that I have amassed around 200 pieces of various sizes. This includes some Guatemalan figures. I went to Guatemala in 2009 and 2010. Since I divide my time between a house in Alexandria, VA, an apartment in Manhattan, and a studio in Chelsea, a portion of my folk art collection resides in each of these places.

Since 2017 I have been creating pastel paintings in the “Bolivianos” series, which exclusively use my photographs of Bolivian Carnival masks as source material. Occasionally, I will add one of my smaller Mexican or Guatemalan figures to improve and enrich a painting’s composition. Otherwise, my Mexican collection sits gathering dust. My thinking and my ideas, not to mention my travels, have evolved and just naturally moved on with time.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 625

Downtown Manhattan

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Think of one of those rare, truly exceptional outings to the cinema. In the lobby afterward the experience elicits from us a language of paralysis and disappearance: “I forgot myself. It could have gone on forever.” Stepping out onto the street, we feel that somehow nothing is as it was before. The passing cars, the night sky above the glass towers, the streetlights reflected on the wet pavement: everything glows with a strange immediacy and newness. It is as if the film had done something to the world. A similar thing might happen when we put down a great novel or take in a powerful piece of music.

The Book of Revelation contains a memorable line: “Behold, I make all things new.” Reflecting on this ancient text, the critic Northrop Frye defined the Apocalypse as “the way the world looks once the ego has disappeared.” Every great artistic work is a quiet apocalypse. It tears off the veil of ego, replacing old impressions with new ones at once inexorably alien and profoundly meaningful. Great works of art have a unique capacity to arrest the discursive mind, raising it to a level of reality that is more expansive than the egoic dimension we normally inhabit. In this sense, art is the transfiguration of the world.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise,Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Q: It must be tricky moving pastel paintings from your New York studio to your framer in Virginia. Can you explain what’s involved? (Question from Ni Zhu via Instagram)

“Impresario” partially boxed for transport to Virginia

A: Well, I have been working with the same framer for three decades so I am used to the process.

Once my photographer photographs a finished, unframed piece, I carefully remove it from the 60” x 40” piece of foam core to which it has been attached (with bulldog clips) during the months I worked on it. I carefully slide the painting into a large covered box for transport. Sometimes I photograph it in the box before I put the cover on (see above).

My studio is in a busy part of Manhattan where only commercial vehicles are allowed to park, except on Sundays. Early on a Sunday morning, I pick up my 1993 Ford F-150 truck from Pier 40 (a parking garage on the Hudson River at the end of Houston Street) and drive to my building’s freight elevator. I try to park relatively close by. On Sundays the gate to the freight elevator is closed and locked so I enter the building around the corner via the main entrance. I unlock my studio, retrieve the boxed painting, bring it to the freight elevator, and buzz for the operator. He answers and I bring the painting down to my truck. Then I load it into the back of my truck for transport to my apartment.

I drive downtown to the West Village, where I live, and double park my truck. (It’s generally impossible to park on my block). I hurry to unload the painting, bring it into my building, and up to my apartment, all the while hoping I do not get a parking ticket. The painting will be stored in my apartment, away from extreme cold or heat, until I’m ready to drive to Virginia. On the day I go to Virginia, I load it back into my truck. Then I make the roughly 5-hour drive south.

Who ever said being an artist is easy was lying!

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 434

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

What do we carry forward? My family lived in New Jersey near Manhattan until I was ten, and although I have enjoyed spending my adult life as a photographer in the American West, when we left New Jersey for Wisconsin in 1947 I was homesick.

The only palliative I recall, beyond my parents’ sympathy was the accidental discovery in a magazine of pictures by a person of whom I had never heard but of scenes I recognized. The artist was Edward Hopper and one of the pictures was of a woman sitting in a sunny window in Brooklyn, a scene like that in the apartment of a woman who had cared for my sister and me. Other views resembled those I recalled from the train to Hoboken. There was also a picture inside a second-floor restaurant, one strikingly like the restaurant where my mother and I occasionally had lunch in New York.

The pictures were a comfort but of course none could permanently transport me home. In the months that followed, however, they began to give me something lasting, a realization of the poignancy of light. With it, all pictures were interesting.

Robert Adams in Art Can Help