Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 546

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Of a thousand years of joys and sorrows

Not a trace can be found

You who are living, live the best life you can

Don’t count on the earth to preserve memory

Ai Weiwei quoting lines written by his father in 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2023, An Artist's Life, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 546

Tags: Ai Weiwei, ”1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows”, documentary, father, frame grab, Jennifer Cox, living, memory, preserve, quoting, sorrows, thousand

Pearls from artists* # 515

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

“Under [General Francisco] Franco,” he said, “attendance at Catholic holidays was obligatory and much Catalan folklore was banned. People avoided the religious processions and, once they were no longer mandatory, ignored them… Marvesa’s [Spain] festive license of demons and dragons is no longer of darkness. If Franco claimed the mantle of Catholic light, then to party as Catalan devils is a happy celebration of freedom.

Demons and dragons are a customary feature of saints’ days and Corpus-Christi festivals throughout Spain and its former empire. They are also common in Carnivals. Indeed, it is partly because of the presence of demons, dragons, and other masked transgressive figures that Carnival has been so often designated – by defenders and detractors alike – as a pagan or devilish season, a time of unrestrained indulgence before the ascetic penances of Lent.

Julio Caro Baroja, the father of Spanish Carnival studies, scorned the antiquarian notion that the masked figures and seasonal inversions of Carnival were “a mere survival” of ancient pagan rituals. Carnival, he argued, was first nurtured by the dualistic oppositions of Christianity. Where it survives – for when he wrote it had been banned by Franco – it still enacts these old antagonisms. “Carnival,” he concluded, “is the representation of paganism itself face-to-face with Christianity.”

... Peter Burke, one of the more lucid historians of popular culture, has proposed that “there is a sense in which every festival [in early modern Europe] was a miniature Carnival because it was an excuse for disorder and because it drew from the same repertoire of traditional forms.

Max Harris in Carnival and Other Christian Festivals: Folk Theology and Folk Performance

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2022, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes, Source Material

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 515

Tags: "The Orator", "Carnival and Other Christian Festivals: Folk Theology and Folk Performmance", aescetic, ancient, antagonisms, antiquarian, argued, attendance, avoided, banned, Carnivals, Catalan, Catholic, celebration, Christianity, claimed, common, Corpus-Christi, culture, customary, darkness, defenders, demons, designated, detractors, devilish, disorder, dragons, dualistic, empire, enacts, Europe, excuse, face-to-face, father, feature, festivals, festive, figures, folklore, former, Franco, freedom, historians, holidays, ignored, indulgence, inversions, itself, Julio Caro Baroja, license, longer, mandatory, mantle, Marvesa, masked, Max Harris, miniature, modern, nurtured, obligatory, oppositions, paganism, penances, people, Peter Burke, popular, presence, processions, proposed, religious, repertoire, representation, rituals, saints, sandpaper, scorned, season, seasonal, soft pastel on sandpaper, Spain, Spanish, studies, survival, survives, throughout, traditional, transgressive, unrestrained

Pearls from artists* # 494

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Emile Cartailhac was a man who could admit when he was wrong. This was fortunate, because in 1902 the French prehistorian found himself writing an article for L’Anthropolgie in which he did just that. In “Mea culpa d’un sceptique” he recanted the views he had spent the previous 20 years forcefully and scornfully maintaining: that prehistoric man was incapable of fine artistic expression and that the cave paintings found in Altmira, northern Spain, were forgeries.

The Paleothithic paintings at Altamira, which were produced around 14,000 B.C., were the first examples of prehistoric cave art to be officially discovered. It happened by chance in 1879, when a local landowner and amateur archaeologist was busily brushing away at the floor of the caves, searching for prehistoric tools. His nine-year-old daughter, Maria Sanz de Sautuola – a grave little thing with cropped hair and lace-up booties – was exploring farther on when she suddenly looked up, exclaiming, “Look, Papa, bison!” She was quite right: a veritable herd, subtly colored with black charcoal and ocher, ranged over the ceiling. When her father published the finding in 1880, he was met with ridicule. The experts scoffed at the very idea that prehistoric man – savages really – could have produced sophisticated polychrome paintings. The esteemed Monsieur Cartailhac and the majority of his fellow experts, without troubling to go and see the cave for themselves, dismissed the whole thing as a fraud. Maria’s father died, a broken and dishonored man, in 1888, four years before Cartailhac admitted his error.

After the discovery of many more caves and hundreds of lions, handprints, horses, women, hyenas, and bison, the artistic abilities of prehistoric man are no longer in doubt. It is thought that these caves were painted by shamans trying to charm a steady supply of food for their tribes. Many were painted using the pigment most readily available in the caves at the time: the charred stick remnants of their fires. At its simplest, charcoal is the carbon-rich by-product of organic matter – usually wood – and fire. It is purest and least ashy when oxygen has been restricted during it’s heating.

In The Secret Lives of Color by Kassia St. Clair

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2022, Art in general, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes, Working methods

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 494

Tags: "Broken", "Mea culpa d'un sceptique", "The Secret Lives of Color", abilities, admitted, Altamira, amateur, archaeologist, article, artistic, available, before, Bolivia, booties, brushing, busily, by chance, by-product, carbon-rich, cave art, cave paintings, ceiling, charcoal, charred, colored, cropped, daughter, discovered, discovery, dishonored, dismissed, drawing, Emile Cartailhac, esteemd, examples, exclaiming, experts, exploring, expresssion, farther, father, finding, forcefully, forgeries, fortunate, handprints, happened, heating, horses, hundreds, hyenas, incapable, Kassia St. Clair, L'Anthropologie, lace-up, landowner, longer, looked, maintaining, majority, Maris Sanz de Sautola, matter, Monsiuer, northern, officially, organic, oxygen, painted, paintings, Paleothithic, pigment, polychrome, prehistorian, prehistoric, preliminary, previous, produced, published, purest, ranged, readily, really, recanted, remnants, restricted, ridicule, savages, scoffed, scornfully, searching, shamans, simplest, sophisticated, steady, subtly, supply, thought, Tiwanaku, tribes, troubling, trying, usually, veritable, Writing

Pearls from artists* # 398

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Marcus Aurelius asks us to note the passing of time with open eyes. Ten thousand years or ten thousand days, nothing can stop time, or change the fact that I would be turning seventy years old in the Year of the Monkey. Seventy. Merely a number but one indicating a significant percentage of the allotted sand in an egg timer, with oneself the darn egg. The grains pour and I find myself missing the dead more than usual. I notice that I cry more when watching television, triggered by romance, a retiring detective hit in the back while staring into the sea, a weary father lifting his infant from a crib. I notice that my own tears burn my eyes, that I am no longer a fast runner and that my sense of time seems to be accelerating.

Patty Smith in Year of the Monkey

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2020, An Artist's Life, Pearls from Artists, Quotes, Sri Lanka

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 398

Tags: accelerating, allotted, “Year of the Monkey”, detective, egg timer, father, indicating, infant, lifting, longer, Marcus Aurelius, missing, myself, Negombo, notice, oneself, open eyes, passing of time, Patti Smith, percentage, retiring, romance, runner, sense of time, significant, Sri Lanka, staring, television, the dead, triggered, turning, watching

Pearls from artists* # 379

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Elaine’s and Bill’s [de Kooning] relationship involved a continual exchange of ideas that wasn’t restricted to conversations with friends. In the quiet of their studio when they were finally alone, they’d climb into bed and Elaine would read to Bill. Faulkner was a favorite. She also read Ambrose Bierce’s Civil War tales. And she would read Kierkegaard. That nineteenth-century father of Existentialism wrote with great passion about the essential solitude and uncertainty of the human struggle. They were words of consolation for Bill and Elaine who, though confident in their paths as artists, could not have been free of the nagging fear that they might spend their lives looking and never find what they sought in their work. Kierkegaard seemed to say that it didn’t matter, that it was striving that counted, and he described the need to reconcile oneself to the unknowable that was man’s fate. The artist, he said, had a crucial role to play in that regard. Like a religious figure who was an envoy from a realm most people could not access, the artist through his or her work revealed pure spirit so that men mired in the bitter reality of daily life might find the strength to continue.

Mary Gabriel in Ninth Street Women

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2019, An Artist's Life, Art in general, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists

Tags: "Blind Faith", access, Ambrose Bierce, artists, “Ninth Street Women”, Bill de Kooning, bitter, Civil War tales, confident, consolation, continual, conversations, Counted, crucial, daily life, described, Elaine de Kooning, essential, exchange, Existentialism, father, Faulkner, favorite, friends, human struggle, involved, Kierkegaard, looking, Mary Gabriel, nagging, passion, people, pure spirit, reality, realm, reconcile, relationship, religious figure, restricted, revealed, soft pastel on sandpaper, solitude, strength, striving, Studio, uncertainty, unknowable

Pearls from artists* # 359

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The Matador, with a black mask made of plaster and stucco, jumps around and teases the pair of bulls. He wears an embroidered cloth on his chest that is draped over his shoulder to cover part of his back. In his hand he carries a saber that was cut out of a barrel or a tin oil can, the way I saw my father and my grandfather make. It has little bells made of beer and other bottle caps, that are flattened into rattles. The matador also wears a colorful diamond shaped montera (cap).

“An Aymara Vision of the Altiplano Masks,” texts and photos by Sixto Choque in Masks of the Bolivian Andes, Editorial Quipos and Banco Mercantil

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2019, Bolivia, Bolivianos, Creative Process, Inspiration, Photography, Source Material

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 359

Tags: "An Aymara Vision of the Altiplano Masks", "Masks of the Bolivian Andes", Banco Mercantil, barrel, bottle caps, carries, colorful, diamond, draped, Editorial Quipos, embroidered, father, flattened, grandfather, jumps around, Matador, montera, oil can, photos, plaster, rattles, saber, shoulder, Sixto Choque, stucco

Q: Where did you grow up and what were some early milestones or experiences that contributed to you becoming an artist later in life?

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

A: I grew up in a blue collar family in Clifton, New Jersey, a suburb about fifteen miles west of Manhattan. My father was a television repairman for RCA. My mother stayed home to raise my sister and me (at the time I had only one sister, Denise; my sister Michele was born much later). My parents were both first-generation Americans and no one in my extended family had gone to college yet. I was a smart kid who showed some artistic talent in kindergarten and earlier. I remember copying the Sunday comics, which in those days appeared in all the newspapers, and drawing small still lifes I arranged for myself. I have always been able to draw anything, as long as I can see it.

Denise, a cousin, and I enrolled in Saturday morning “art classes” at the studio of a painter named Frances Hulmes in Rutherford, NJ. I was about 6 years old. I continued the classes for 8 years and became a fairly adept oil painter. Since we lived so close to New York City, my mother often took us to museums, particularly to the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Natural History. Like so many young girls, I fell in love with Rousseau’s “The Sleeping Gypsy” and was astonished by Picasso’s “Guernica” when it was on long-term loan to MoMA. I have fond memories of studying the dioramas at the Museum of Natural History (they are still my favorite part of the museum). As far as I know, there were no artists in my family so, unfortunately, I had no role models. At the age of 14 my father decided that art was not a serious pursuit – declaring, it is “a hobby, not a profession” – and abruptly stopped paying for my Saturday morning lessons. With no financial or moral support to pursue art, I turned my attention to other interests, letting my artistic abilities go dormant.

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2019, An Artist's Life, Art in general, Painting in General

Comments Off on Q: Where did you grow up and what were some early milestones or experiences that contributed to you becoming an artist later in life?

Tags: "a hobby not a profession"paying, "Guernica", "Sleeping Gypsy", abilities, abruptly, Americans, anything, arranged, art classes, artist, artistic, artists, attention, blue collar, Clifton, college, contribute, copying, cousin, decided, dioramas, dormant, drawing, earlier, enrolled, experiences, extended family, family, father, first-generation, Frances Hulmes, Henri Rousseau, interests, kindergarten, Manhattan, memories, Metropolitan Museum of Art, milestones, morning, mother, museum, Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Natural History, myself, New Jersey, New York City, newspapers, oil on canvas, oil painter, painter, Picasso, pursuit, remember, role models, Rousseau, Rutherford, Saturday, serious, sister, still-lifes, stopped, studying, suburb, Sunday comics, talent, television repairman

Q: Can you speak about a book (or books) that deeply influenced you as an artist?

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

A: One such book that stands out is “Camille Pissaro: Letters to His Son Lucien.” The book is comprised of weekly letters from a father conveying wisdom about his craft, art, and life, over roughly twenty years, to a beloved son, who is just beginning his artistic journey. I discovered this gem about thirty years ago when I was just starting to find my way as an artist, too. Pissarro’s words are beautiful, poignant, and deeply felt. He has much to say to artists because, sadly, we still contend with the same problems, such as how to remain authentic and earn a living, how to deal with galleries and collectors, how to stay focused on the work, etc. I often enjoy rereading favorite passages simply because it makes me feel less alone as an artist.

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2016, An Artist's Life, Art in general, Creative Process, Inspiration, Photography

Comments Off on Q: Can you speak about a book (or books) that deeply influenced you as an artist?

Tags: "Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son Lucien", artist, artistic, authentic, beautiful, because, beginning, beloved, collectors, comprised, contend, conveying, deeply, discovered, father, focused, galleries, influenced, journey, letters, living, often, Pissaro, poignant, problems, remain, rereading, roughly, simply, starting, twenty, weekly, well-worn, wisdom

Q: Were there any other artists in your family?

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

A: Unfortunately, I have not been able to reconstruct my family tree further back than two generations. So as far as I can tell, I am the first artist of any sort, whether musician, actor, dancer, writer, etc. in my family.

Both sets of grandparents emigrated to the United States from Europe. On my mother’s side my Polish grandparents died by the time my mother was 16, years before I was born.

My paternal grandparents both lived into their 90s. My father’s mother spoke Czech, but since I did not, it was difficult to communicate. I never heard any stories about the family she left behind. My grandfather spoke English, but I don’t remember him ever talking about his childhood or telling stories about his former life. My most vivid memories of my grandfather are seeing him in the living room watching Westerns on an old-fashioned television.

Sometimes I am envious of artists who had parents, siblings, or extended family who were artists. How I would have loved to grow up with a family member who was an artist and a role model!

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2015, An Artist's Life, Art in general, Black Paintings, Creative Process, Inspiration, Pastel Painting, Photography

Tags: "The Ancestors", able, actor, always, artists, behind, being, Czech, dancer, date, disadvantages, emigrated, English, envious, Europe, extended, family, father, generations, grandfather, grandparents, inspiring, life, little, lived, loved, memories, mother, musician, often, Old-fashioned, parents, pastel, paternal, Polish, reconstruct, remember, role model, sandpaper, siblings, sitting, soft, sometimes, spoke, stories, television, telling, understood, unfortunately, United States, visual, vivid, watching, Westerns, writer

Q: Your relationship with photography has changed considerably over the years. How did you make use of photography in your first series of pastel-on-sandpaper paintings, “Domestic Threats”?

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

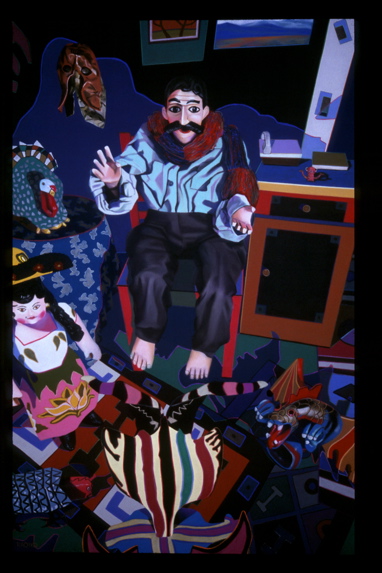

“Truth Betrayed by Innocence,” 2001, 58″ x 38″, the last pastel painting for which Bryan photographed the setup

A: When my husband, Bryan, was alive I barely picked up a camera, except to photograph sights encountered during our travels. Throughout the 1990s and beyond (ending in 2007), I worked on my series of pastel-on-sandpaper paintings called, “Domestic Threats.” These were realistic depictions of elaborate scenes that I staged in our 1932 Sears house in Alexandria, Virginia, and later, in a New York sixth floor walk-up apartment, using the Mexican masks, carved wooden animals, and other folk art figures that I found on our trips to Mexico. I staged and lit these setups, while Bryan photographed them using his Toyo-Omega 4 x 5 view camera. We had been collaborating this way almost from the beginning (we met on February 21, 1986). Having been introduced to photography by his father at the age of 6, Bryan was a terrific amateur photographer. He would shoot two pieces of 4 x 5 film at different exposures and I would select one, generally the one that showed the most detail in the shadows, to make into a 20 x 24 photograph. The photograph would be my starting point for making the pastel painting. Although I work from life, too, I could not make a painting without mostly looking at a reference photo. After Bryan was killed on 9/11, I had no choice but to study photography. Over time, I turned myself into a skilled photographer.

Comments are welcome!

Posted in 2013, An Artist's Life, Creative Process, Domestic Threats, Inspiration, Mexico, New York, NY, Pastel Painting, Photography, Travel, Working methods

Tags: "Truth Betrayed by Innocence", 1932, 1990s, 20 x 24 photograph, 2001, 2007, 4 x 5 film, 4 x 5 view camera, 9/11, Alexandria (VA), amateur, apartment, beginning, Bryan Jack, camera, carved wooden animals, change, collaborating, depictions, detail, different, elaborate, ending, exposures, father, figures, first, folk art, found, husband, introduce, killed, lit, look, masks, Mexican, Mexico, New York, pastel painting, photograph, photographer, photography, realistic, reference photo, relationship, scene, Sears house, setup, shadows, shoot, sights, skilled, staged, starting point, study, Toyo-Omega, travel, trip, use, way, work from life, years