Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 468

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Why does art elicit such different reactions from us? How can a work that bowls one person over leave another cold? Doesn’t the variability of the aesthetic feeling support the view that art is culturally determined and relative? Maybe not, if we consider the possibility that the artistic experience depends not on some subjective mood but on an individually acquired (hence variable) power to be affected by art, a capacity developed through one’s culture in tandem with one’s unique character. For evidence of this we can point to works that seem to ignore cultural boundaries altogether, affecting people of different backgrounds in comparable ways even though a specific articulation of their personal responses continues to vary. Consider the plays of William Shakespeare or Greek theater, or the fairy tales that have sprung up in similar forms on every continent. We could not be further removed from the people who painted in the Chauvet Cave, nor could we be more oblivious as to the significance they ascribed to their pictures. Yet their work affects us across the millennia. Everyone responds to them differently, of course, and the spirit in which people are likely to receive them now probably differs significantly from how it was at the beginning. But these permutations revolve around a solid core, something present in the images themselves.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 461

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

I must not eat much in the evening, and I must work alone. I think that going into society from time to time, or just going out and seeing people, does not do much harm to one’s work and spiritual progress, in spite of what many so-called artists say to the contrary. Associating with people of that kind is far more dangerous; their conversation is always commonplace. I must go back to being alone. Moreover, I must try to live austerely, as Plato did. How can one keep one’s enthusiasm concentrated on a subject when one is always at the mercy of other people and in constant need of their society? Dufresne was perfectly right; the things we experience for ourselves when we are alone are much stronger and much fresher. However pleasant it may be to communicate one’s emotion to a friend there are too many fine shades of feeling to be explained, and although each probably perceives them, he does so in his own way and thus the impression is weakened for both. Since Dufresne has advised me to go to Italy alone, and to live alone once I am settled there, and since I, myself, see the need for it, why not begin now to become accustomed to the life; all the reforms I desire will spring from that? My memory will return, and so will my presence of mind, and my sense of order.

The Journal of Eugene Delacroix edited by Hubert Wellington

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 197

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

As Kenneth Burke says in ‘Counter-Statement:’ “[Great] artists feel as opportunity what others feel as menace. This ability does not, I believe, derive from exceptional strength, it probably arises purely from professional interest the artist may take in his difficulties.”

Marianne Moore in Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews Second Series, edited by George Plimpton

Comments are welcome!

Q: How many studios have you had since you’ve been a professional artist?

A: I am on my third, and probably last, studio. I say ‘probably’ because I love my space and have no desire to move. Plus, it would be a tremendous amount of work to relocate, considering that I have been in my West 29th Street studio since 1997.

My very first studio, in the late 1980s, was the spare bedroom of my house in Alexandria, Virginia. I set up a studio there while I was on active duty in the Navy. When I resigned my commission, I was required to give the President an entire year’s advance notice. Towards the end of that year I remember calling in sick so I could stay home and make art.

In the early 1990s I rented a studio on the third floor of the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria. For a while I enjoyed working there, but the constant interruptions – in an art center that is open to the public – became tiresome.

In 1997 I had the opportunity to move to New York. I desperately craved solitary hours to work in peace, without interruption, so at first I didn’t have a telephone. I still don’t have WiFi there because my studio is reserved strictly for creative work.

Moving from Virginia to New York in 1997 was relatively easy. My aunt, who planned to be in California to continue her Buddhist studies, offered me her rent-controlled sixth-floor walkup on West 13th Street. I looked at just one other studio before signing a sublease for my space at 208 West 29th Street. I had heard about the vacancy through a college friend of my husband, Bryan. Karen, the lease-holder, was relocating to northern California to work on “Star Wars” with George Lucas. After several years, she decided not to return to New York and I have been the lease-holder ever since.

Comments are welcome!

Q: What was the first painting you ever sold?

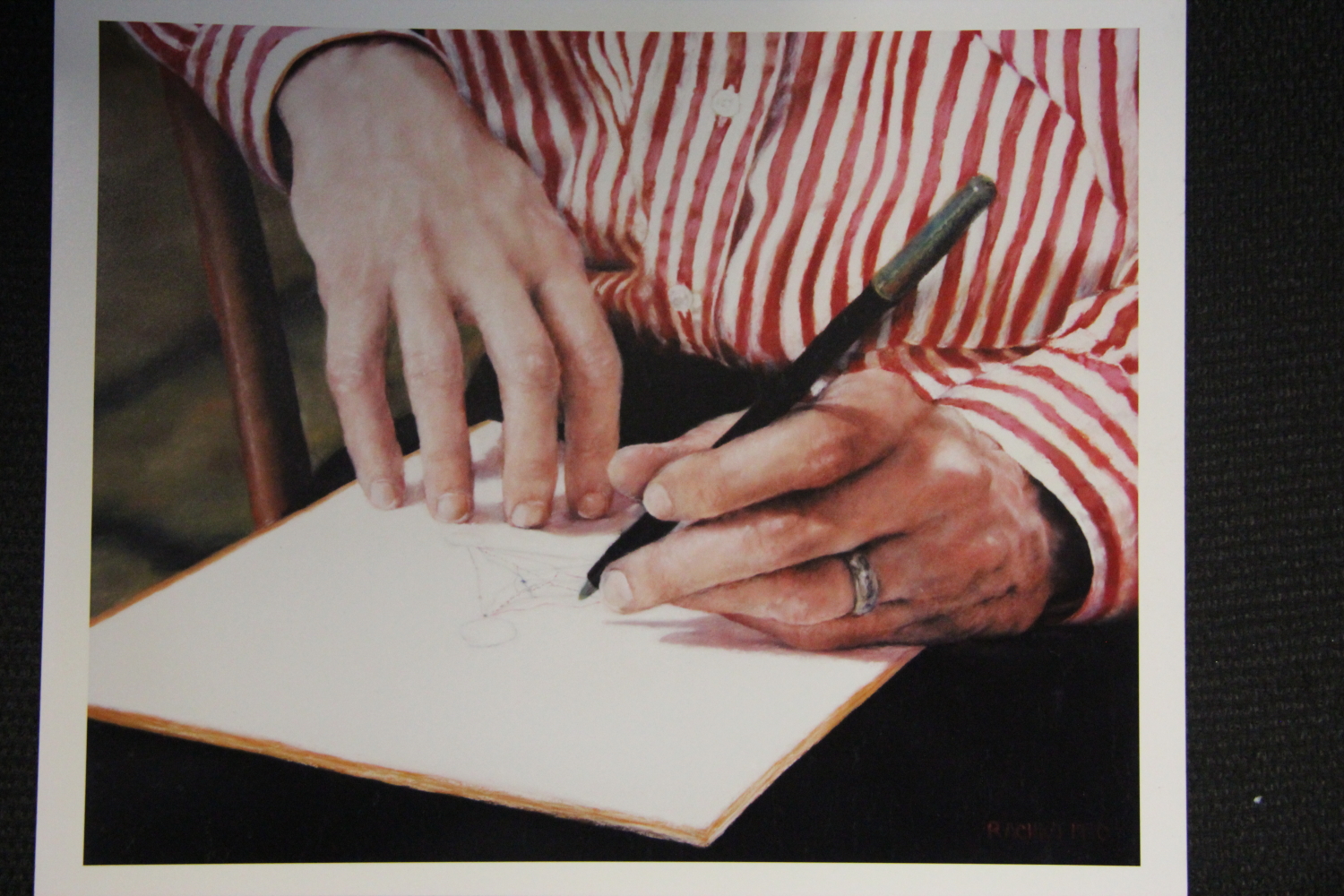

A: I believe my first sale was “Bryan’s Ph.D.” I made it in 1990 as one of several small paintings created to improve my skills at rendering human hands in pastel. I had recently left the Navy and was building a career as a portrait artist. Bryan, my late husband, was often my model for these studies, not only because it was convenient, but because he had such beautiful hands.

In 1990 Bryan was working on his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Maryland. In this painting he is drawing a diagram that illustrates a theoretical point about “international public goods,” the subject of his research. He was sitting in an old wooden rocking chair in our backyard in Alexandria, VA. I still own the chair and the house. I photographed his hands close-up and then created the painting. I don’t remember which of Bryan’s cameras I used, but it was one that took 35 mm film; perhaps his Nikon F-2. Somewhere I must still have the negative and the original reference photo.

“Bryan’s Ph.D.” is 11″ x 13 1/2″ and it sold for $500 at a monthly juried exhibition at The Art League in Alexandria. I have not seen it since 1990. (Above is a photograph of “Bryan’s Ph.D.” from my portfolio book).

Not long ago the owner contacted me, explaining that she had received the painting as a gift from her now ex-husband. She was selling it because it evoked bitter memories of her divorce. Her phone call was prompted by uncertainty about the painting’s value now. She had a likely buyer and needed to know what price to charge.

I was saddened because I have so many beautiful memories of this particular painting and of an idyllic time in my life with Bryan. He was on a leave of absence from the Pentagon to work on his dissertation, while I was finished with active duty. At last I was a full time artist, busily working in the spare bedroom that we had turned into my first studio.

My conversation with the owner was a reminder that once paintings are let out into the world, they take on associations that have nothing to do with the personal circumstances surrounding their creation. In short, what an artist creates solely out of love, stands a good chance of not being loved or appreciated by others. This is one reason to only sell my work to people I select personally. I ended the telephone conversation hoping that “Bryan’s Ph.D.” fares better in its new home.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Can you talk a little bit about your process? What happens before you even begin a pastel painting?

A: My process is extremely slow and labor-intensive.

First, there is foreign travel – often to Mexico, Guatemala or someplace in Asia – to find the cultural objects – masks, carved wooden animals, paper mâché figures, and toys – that are my subject matter. I search the local markets, bazaars, and mask shops for these folk art objects. I look for things that are old, that look like they have a history, and were probably used in religious festivals of some kind. Typically, they are colorful, one-of-a- kind objects that have lots of inherent personality. How they enter my life and how I get them back to my New York studio is an important part of my art-making practice.

My working methods have changed dramatically over the nearly thirty years that I have been an artist. My current process is a much simplified version of how I used to work. As I pared down my imagery in the current series, “Black Paintings,” my creative process quite naturally pared down, too.

One constant is that I have always worked in series with each pastel painting leading quite naturally to the next. Another is that I always set up a scene, plan exactly how to light and photograph it, and work with a 20″ x 24″ photograph as the primary reference material.

In the setups I look for eye-catching compositions and interesting colors, patterns, and shadows. Sometimes I make up a story about the interaction that is occurring between the “actors,” as I call them.

In the “Domestic Threats” series I photographed the scene with a 4″ x 5″ Toyo Omega view camera. In my “Gods and Monsters” series I shot rolls of 220 film using a Mamiya 6. I still like to use an old analog camera for fine art work, although I have been rethinking this practice.

Nowadays the first step is to decide which photo I want to make into a painting (currently I have a backlog of photographs to choose from) and to order a 19 1/2″ x 19 1/2″ image (my Mamiya 6 shoots square images) printed on 20″ x 24″ paper. They recently closed, but I used to have the prints made at Manhattan Photo on West 20th Street in New York. Now I go to Duggal. Typically I have in mind the next two or three paintings that I want to create.

Once I have the reference photograph in hand, I make a preliminary tonal charcoal sketch on a piece of white drawing paper. The sketch helps me think about how to proceed and points out potential problem areas ahead.

Only then am I ready to start actually making the painting.

Comments are welcome!