Blog Archives

Q: How do you organize your studio?

A: Of course, my studio is first and foremost set up as a work space. The easel is at the back and on either side are two rows of four tables, containing thousands of soft pastels.

Enticing busy collectors, critics, and gallerists to visit is always difficult, but sometimes someone wants to make a studio visit on short notice so I am ready for that. I have a selection of framed recent paintings and photographs hanging up and/or leaning against a wall. For anyone interested in my evolution as an artist, I maintain a portfolio book with 8″ x 10″ photographs of all my pastel paintings, reviews, press clippings, etc. The portfolio helps demonstrate how my work has changed during my nearly three decades as a visual artist.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Why do you need to use a photograph as a reference source to make a pastel painting?

A: When I was about 4 or 5 years old I discovered that I had a natural ability to draw anything that I could see. It’s the way my brain is wired and it is a gift! One of my earliest memories as an artist is of copying the Sunday comics. Always it has been much more difficult to draw what I CANNOT see, i.e., to recall how things look solely from memory or to invent them outright.

The evolution of my pastel-on-sandpaper paintings has been the opposite of what one might expect. I started out making extremely photo-realistic portraits. I remember feeling highly unflattered when after months of hard work, someone would look at my completed painting and say, “It looks just like a photograph!” I know this was meant as a compliment, but to me it meant that I had failed as an artist. Art is so much more than copying physical appearances.

So I resolved to move away from photo-realism. It has been slow going and part of me still feels like a slacker if I don’t put in all the details. But after nearly three decades I have arrived at my present way of working, which although still highly representational, contains much that is made up, simplified, and/or stylized. As I have always done, I continue to work from life and from photographs, but at a certain point I put everything aside and work solely from memory.

Comments are welcome!

Q: What’s on the easel today?

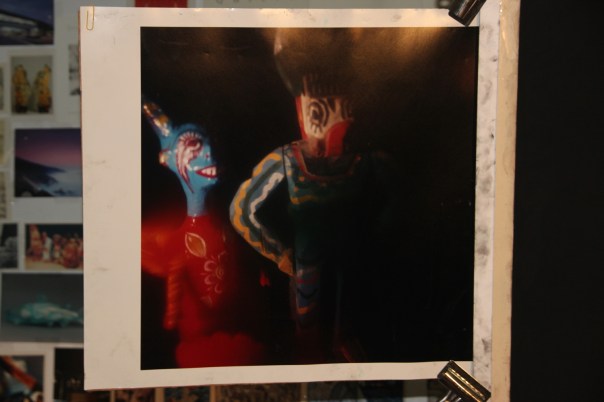

A: Today is a day off to let my fingers heal. When I start a new painting, I need to rub my fingers against raw sandpaper in order to blend the pastel. With each layer the tooth of the paper gets filled up and becomes smooth, but until then my fingers suffer. Here is what I’ve been working on.

This pastel-on-sandpaper painting is an experiment, an attempt to push myself to work with bigger and bolder imagery. The photograph clipped to the easel is one of my favorites. It depicts a Judas that Bryan and I found in a dusty shop in Oaxaca. Among the Mexican and Guatemalan folk art pieces that I’ve collected are five papier mâché Judases. This particular one is unusual because it has a cat’s head attached at the forehead (the purple shape in the painting). They are not made to last. In some Mexican towns large Judases are hung from church steeples, loaded with fireworks, and burned in effigy. This takes place at 10:00 a.m. on the Saturday morning before Easter. Mexico is primarily a Catholic nation, of course, so effigy burning is done as symbolic revenge against Judas for his betrayal of Christ. The Judas in the photo is small and meant for private burning by a family (rather than in public at a church) so by bringing it back to New York I rescued it from a fire-y death! In sympathy with Mexican tradition, I began this painting last Saturday (the day before Easter) at 10 a.m.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 34

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

To collect photographs is to collect the world. Movies and television programs light up walls, flicker, and go out; but with still photographs the image is also an object, lightweight, cheap to produce, easy to carry about, accumulate, store.

In Godard’s Les Carabiniers (1963), two sluggish lumpen-peasants are lured into joining the king’s army by the promise that they will be able to loot, rape, kill, or do whatever else they please to the enemy, and get rich. But the suitcase of booty that Michel-Ange and Ulysse triumphantly bring home, years later, to their wives turns out to contain only picture postcards, hundreds of them, of monuments, department stores, mammals, wonders of nature, methods of transport, works of art, and other classified treasures from around the globe.

Godard’s gag vividly parodies the equivocal magic of the photographic image. Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up, and thicken, the environment we recognize as modern.

Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.

Susan Sontag in On Photography

Comments are welcome!

Q: Your new work explores relationships to figures through the medium of soft pastel. What prompted this departure from photography?

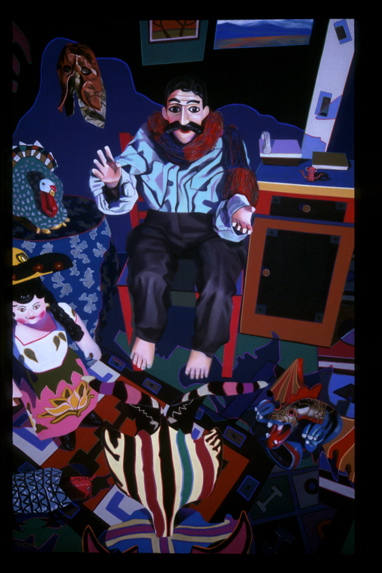

A: Actually it was the other way around. As I’ve mentioned, I was a maker of pastel-on-sandpaper paintings long before I became a photographer (1986 vs. 2002). However, the photos in the “Gods and Monsters” series were meant to be photographs in their own right, i.e., they were not made to be reference material for paintings. in an interesting turn of events, in 2007 I started a new series, “Black Paintings,” which uses the “Gods and Monsters” photographs as source material. Collectors who have been following my work for years tell me the new series is the strongest yet. For now I’m enjoying where this work is leading. The last three paintings are the most minimal yet and I’ve begun thinking of them as the “Big Heads.” There is usually a single figure (“Stalemate” has two) that is much larger than life size. “Epiphany” (above, left) is an example. All of them are quite dramatic when seen in person, especially with their black wooden frames and mats.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 27

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Of course, when people said a work of art was interesting, this did not mean that they necessarily liked it – much less that they thought it beautiful. It usually meant no more than that they thought they ought to like it. Or that they liked it, sort of, even though it wasn’t beautiful.

Or they might describe something as interesting to avoid the banality of calling it beautiful. Photography was the art where “the interesting” first triumphed, and early on: the new, photographic way of seeing proposed everything as a potential subject for the camera. The beautiful could not have yielded such a range of subjects; and it soon came to seem uncool to boot as a judgment. Of a photograph of a sunset, a beautiful sunset, anyone with minimal standards of verbal sophistication might well prefer to say, “Yes, the photograph is interesting.”

What is interesting? Mostly, what has not previously been thought beautiful (or good). The sick are interesting, as Nietzsche points out. The wicked, too. To name something as interesting implies challenging old orders of praise; such judgments aspire to be found insolent or at least ingenious. Connoisseurs of “the interesting” – whose antonym is “the boring” – appreciate clash, not harmony. Liberalism is boring, declares Carl Schmitt in The Concept of the Political, written in 1932. (The following year he joined the Nazi Party). A politics conducted according to liberal principles lacks drama, flavor, conflict, while strong autocratic politics – and war – are interesting.

Paolo Dilonardo and Anne Jump, editors, Susan Sontag: At the Same Time

Comments are welcome!