Blog Archives

Q: Does your work look different to you on days when you are sad, happy, etc.?

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

Barbara’s Studio

A: I am much more critical on days when I am sad so that the faults, imperfections, and things I wish I had done better stand out. Fortunately, all of my work is framed behind plexiglas so I can’t easily go back in to touch up perceived faults. I am reminded of the expression, “Always strive to improve, whenever possible. It is ALWAYS possible!” However, I’ve learned that re-working a painting is a bad idea. You are no longer deeply involved in making it and the zeitgeist has changed. The things you were concerned with are gone: some are forgotten, others are less urgent.

For most artists our work is autobiography. Art is personal. When I look at a completed pastel painting, I usually remember exactly what was happening in my life as I created it. Each piece is a snapshot – maybe a time capsule, if anyone could decode it – that reflects and records a particular moment. When I finally pronounce a piece finished and sign it, that’s it, THE END. It’s as good as I can make it at that point in time. I’ve incorporated everything I was thinking about, what I was reading, how I was feeling, what I valued, art exhibitions I visited, programs that I heard on the radio or watched on television, music that I listened to, what was going on in New York, in the country, and in the world.

It is still a mystery how this heady mix finds its way into the work. During the time that I spend on it, each particular painting teaches me everything it has to teach. A painting requires months of looking, reacting, correcting, searching, thinking, re-thinking, revising. Each choice is made for a reason and together these decisions dictate what the final piece looks like. On days when I’m sad I tend to forget that. On happier days I remember that the framed pastel paintings that you see have an inevitability to them. If all art is the result of one’s having gone through an experience to the end, as I believe it is, then the paintings could not, and should not, look any differently.

Comments are welcome.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2025, An Artist's Life, Creative Process, Studio, Uncategorized

Comments Off on Q: Does your work look different to you on days when you are sad, happy, etc.?

Tags: always, anyone, artists, autobiography, believe, better, changed, choice, completed, concerned, correcting, country, critical, decisions, decode, deeply, dictate, different, differently, easily, everythibg, everything, exactly, Exhibitions, experience, expression, faults, feeling, finally, finished, forget, forgotten, fortunately, framed, happening, happier, imperfections, improve, incorporated, inevitability, involved, learned, listened, longer, looking, making, moment, mystery, New York, painting, particular, pastel painting, perceived, personal, plexiglas, possible, programs, pronounce, re-thinking, reacting, reading, reason, records, reflects, remember, reminded, result, revising, reworking, searching, snapshot, teaches, television, temember, thinking, time capsule, together, urgent, usually, valued, visited, watched, whenever, zeitgeist

Pearls from artists* # 630

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

With Margaret Anderson, Naoshima, Kagawa, Japan

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Fresh experiences can lead to new tastes and a life that feels longer, Julie contended. Remember when you were little and an hour-long car ride felt like a lifetime? “I think it’s because, truly, everything’s new. When you experience new things, time slows down a little bit,” she told me. “When you go on trips – which is my favorite thing to do – everything is new, and you feel young again. And reinvigorated with new ideas, new perspectives, a new understanding of yourself.”

Julie Curtiss quoted in Get The Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See by Bianca Bosker

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2024, 2024, Inspiration, Japan, Pearls from Artists, Quotes, Travel

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 630

Tags: ”Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See”, Bianca Bosker, car ride, contended, everything, experience, favorite, hour-long, Japan, Julie Curtiss, Kagawa, lifetime, little, longer, Margaret Anderson, Naoshima, perspectives, reinvigorated, remember, things, understanding, yourself

Pearls from artists* # 618

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

Lower Manhattan

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Today, instead of one voice, we have dozens issuing demands. There is no longer one truth, no single authority – instead there is a score of would-be masters who would usurp their place. All are full of histories, statistics, proofs, demonstrations, facts, and quotations. First they read and exhort, and finally they resort to intimidation by threats and moral imprecations. Each pulls the artist this way and that, telling him what he must do if he is to fill his belly and save his soul.

Mark Rothko in The Artists’ Reality: Philosophies of Art

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2024, An Artist's Life, Inspiration, New York, NY, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 618

Tags: artist, authority, “The Artists’ Reality: Philosophies of Art”, demands, demonstrations, dozens, exhort, finally, histories, imprecations, instead, intimidation, issuing, longer, Lower Manhattan, Mark Rothko, masters, proofs, quotations, resort, single, statistics, telling, threats

Pearls from artists* # 610

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

View from the High Line, New York NY

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Just as the restless, committed, curious, and perhaps obsessed explorer follows the river from bend to bend, shooting rapids and pulling himself out of the water, so the self-dedicated artist launches himself on an exploratory art journey. He judges which fork in the river he will take, when he will rest and when he will push on, who he will take with him or whether he will travel alone. While he doesn’t possess unlimited freedom as he journeys, bound as he is by the demands of his personality, by his time and place, and by circumstances beyond his control, he does possess unrestricted permission from himself to explore every available avenue.

The contemporary artist must especially direct and trust himself because he lives in a constantly changing art environment. … as Pablo Picasso put it, “Beginning with Van Gogh we are all in a measure, autodidacts.” Painters no longer live within a tradition and so each of us must create an entire language.

Eric Maisel in A Life in the Arts: Practical Guidance and Inspiration for Creative and Performing Artists

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2024, An Artist's Life, Creative Process, Inspiration, New York, NY, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 610

Tags: artist, autodidacts, available, avenue, ‘A Life in the Arts: Practical Guidance and Inspiration for Creative and Performing Artists”, beginning, beyond, changing, circumstances, committed, constantly, contemporary, control, curious, demands, direct, entire, environment, Eric Maisel, especially, exploratory, explore, follows, freedom, HighLine, himself, journey, judges, language, launches, longer, measure, New York, obsessed, Pablo Picasso, painters, perhaps, permission, personality, possess, pulling, rapids, re-create, restless, self-directed, shooting, tradition, travel, unlimited, unrestricted, van Gogh, whether

Q: Do you ever erase the color? Can you do that with pastel? (Question from Hollis Hildebrand-Mills via Facebook)

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

My “eraser”

A: Yes, sort of. I take a bristle brush and wipe it off. I do this only occasionally, when the sandpaper’s tooth is filled up and the paper will no longer accept more pastel. So I brush off what’s there and then I can start over.

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2023, Pastel Painting, Working methods

Comments Off on Q: Do you ever erase the color? Can you do that with pastel? (Question from Hollis Hildebrand-Mills via Facebook)

Tags: accept, bristle brush, eraser, Facebook, filled, Hollis Hildebrand-Mills, longer, occasionally, pastel, question, sandpaper

Pearls from artists* # 570

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

Barbara’s Studio

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

One of the main differences between the young girl who drew a line in chalk from the Metropolitan Museum all the way to her home on Park Avenue and the young woman who drew lines on canvas and paper twenty years later was that the latter understood the willfulness that drove the child. She was facing “the monster,” the consuming need to create, which was beyond her control but no longer beyond her comprehension. Helen [Frankenthaler] had long understood that her gift set her apart, and that it would be nearly impossible to describe how and why without sounding arrogant or cruel. “It’s saying I’m different, I’m special, consider me differently,” she explained years later. “And it’s also on the other side, a recognition that one is lonely, that one is not run of the mill, that the values are different, and yet we all go into the same supermarkets… and we are all moved one way or another by children and seasons, and dreams. So that art separates you…”

The separation she described was not merely the result of what one did, whether it be painting or sculpting or writing poetry. Helen said the distance between an artist and society was due to a quality both intangible and intrinsic, a “spiritual” or “magical” aspect that nonartists did not always understand and were sometimes frightened by. “They want you to behave a certain way. They want you to explain what you do and why you do it. Or they want you removed, either put on a pedestal or victimized. They can’t handle it.” Helen concluded that existing outside so-called normal life was simply the price an artist paid to create.

Mary Gabriel in Ninth Street Women

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2023, An Artist's Life, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 570

Tags: always, another, arrogant, aspect, ”Ninth Street Women”, ”the monster”, behave, between, beyond, canvas, certain, children, comprehension, concluded, consider, consuming, control, create, describe, differences, different, distance, dreams, either, existing, explain, facing, frightened, handle, Helen Frankenthaler, impossible, intangible, intrinsic, latter, lonely, longer, magical, Mary Gabriel, merely, Metropolitan Musrum, nearly, need to create, nonartists, normal, other, outside, painting, Park Avenue, pedestal, poetry, quality, recognition, removed, result, run of the mill, saying, sculpting, seasons, separates, separation, simply, so-called, society, sometimes, sounding, special, spiritual, Studio, supermarkets, understand, understood, victimized, whether, willfulness, Writing

Pearls from artists* # 562

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

“Shadow,” soft pastel on sandpaper, 26” x 20,” in progress

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Jung observed that complexes could affect groups of people en masse. He saw that certain moments seemed to be expressions of a collective shadow, a bursting forth of a mass psychosis; the repressed side of a whole group coming alive; a tribal Mr. Hyde. He saw this madness first-hand in Germany in the 1930s and wrote about it. But every era carries some measure of collective shadow.

One could argue that no moment in time has seen more of the reality of human darkness than ours. Having witnessed the Holocaust and faced the threat of nuclear war in the twentieth century, and now facing the environmental impact of fossil fuels and plastics in the twenty-first century, we are undoubtedly aware of more of humanity’s potential for destruction than any of our ancestors ever were. Such a view does not come from a moralizing stance. Our era has made forced witnesses of us all.

The shadow is about where we put the Devil – where do we allow darkness to be housed? Racism and bigotry offer the relief of foisting our group’s shadow onto another whom we view as lesser. Doing so enables us not to look at or feel our shadow, and not see our own worst selves. But this collective shadow of our modern culture is also bigger and wider than group-to-group projections. There are culture-wide or civilization expressions of the collective shadow.

Jung saw the widespread loss of connection to the inner life and to a lived spirituality as one of the primary illnesses of our time. He observed that people were no longer animated by the traditional religions… For Jung, this meant that we’ve lost the old way but not yet found the new, and are sitting in a spiritual vacuum.

Into that vacuum, without our awareness, has slipped our fascination with human technology. Observe people closely today and you’ll notice that we have an almost magical faith in our devices. People see their computers and phones as all-knowing and expect them to function perfectly all the time, and view pharmaceuticals as magic cure-alls. Where we used to put God, we now have put technology. Where spirit was, we have unconsciously placed human genius.

Gary Bobroff in Carl Jung: Knowledge in a Nutshell

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2023, An Artist's Life, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 562

Tags: affect, all-knowing, almost, ancestors, animated, another, awareness, ”Carl Jung: Knowledge in a Nutshell”, ”Shadow”, bigger, bigotry, bursting, Carl Jung, carries, certain, collectuve, coming, complexes, computers, connection, culture, cure-alls, darkness, destruction, devices, en masse, enables, environmental, expect, expressions, facing, fascination, first-hand, foisting, forced, fossil fuels, function, Gary Bobroff, genius, Germany, group-to-group, groupd, Holocaust, housed, humanity, illness, impact, inner life, lesser, longer, madness, magical, measure, modern, moment, moments, moralizing, Mr. Hyde, notice, nuclear war, observe, observed, people, perfectly, pharmaceuticals, phones, placed, plastics, potential, primary, projections, racism, reality, relief, religions, repressed, selves, shadow, sitting, slipped, soft pastel on sandpaper, spirit, spirituality, stance, technology, the Devil, threat, traditional, twentieth century, twenty-first century, unconsciously, undoubtedly, vacuum, widespread, without, witnessed, witnesses

Pearls from artists* # 558

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

Alexandria, VA

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

One of the main differences between the young girl who drew a line in chalk from the Metropolitan Museum all the way to her home on Park Avenue and the young woman who drew lines on canvas and paper twenty years later was that the latter understood the willfulness that drove the child. She was facing “the monster,” the consuming need to create, which was beyond her control but no longer beyond her comprehension. Helen [Frankenthaler] had long understood that her gift set her apart, and that it would be nearly impossible to describe how and why without sounding arrogant or cruel. “It’s saying I’m different, I’m special, consider me differently,” she explained years later. “And it’s also on the other side, a recognition that one is lonely, that one is not run of the mill, that the values are different, and yet we all go into the same supermarkets… and we all are moved one way or the other by children and seasons, and dreams. So the art separates you.”

The separation she described was not merely the result of what one did, whether it be painting or sculpting or writing poetry. Helen said the distance between an artist and society was due to a quality both tangible and intangible and intrinsic, a “spiritual” or “magical” aspect that nonartists did not always understand and were sometimes frightened by. “They want you to behave a certain way. They want you to explain what you do and why you do it. Or they want you removed, either put on a pedestal or victimized. They can’t handle it.” Helen concluded that existing outside so-called normal life was simply the price an artist paid to create.

Mary Gabriel in Ninth Street Women

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2023, Alexandria (VA), An Artist's Life, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 558

Tags: Alexandria_VA, always, arrogant, artist, aspect, “Ninth Street Women”, “the monster”, behave, between, beyond, canvas, certain, children, comprehension, concluded, consider, consuming, control, create, describe, described, differences, different, differently, distance, dreams, either, existing, explain, explained, frightened, handle, Helen Frankenthaler, impossibe, intangible, intrinsic, latter, lonely, longer, magical, Mary Gabriel, merely, Metropolitan Museum, nearly, nonartists, normal, other, outside, painting, Park Avenue, pedestal, poetry, quality, recognition, removed, result, run of the mill, saying, sculpting, seasons, separates, separation, simply, so-called, society, sometimes, sounding, special, spiritual, supermarkets, tangible, understand, understood, values, victimized, whether, willfulness, without, woman, Writing

Pearls from artists* # 516

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on

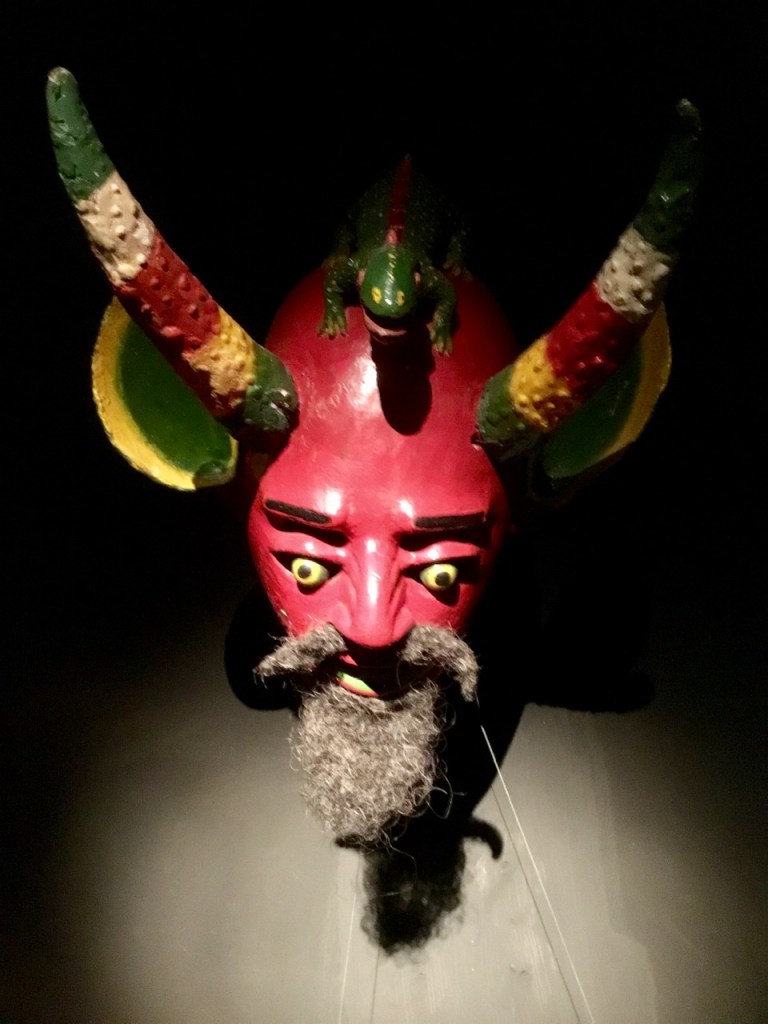

In Oruro, Bolivia, devotion to the Virgin del Socavon (Virgin of the Mineshaft) migrated from the fixed festival of Candlemas (2 February) to the movable feast of Carnival. By delaying their public devotion to the Virgin until the four-day holiday before Ash Wednesday, Oruro’s miners were able to enjoy a longer fiesta than if they had confined it to a single saint’s day. During Oruro’s Carnival, thousands of devils dance through the streets before unmasking in the Sanctuary of the Mineshaft to express devotion to the Virgin.

Evidently, the festive connotation of devils is not always demonic. In Manresa [Spain], the demons and dragons celebrate the restoration of liberty after a brutal civil war and subsequent dictatorship [General Francisco Franco]. In Oruro… the masked devils protest exploitation of indigenous miners by external forces and devote themselves to a Virgin who blesses the poor and marginalized. Festive disorder generally dreams not of anarchy but of a more egalitarian order.

Max Harris in Carnival and other Christian Festivals: Folk Theology and Folk Performance

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2022, Bolivia, Bolivianos, Inspiration, Source Material

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 516

Tags: "Carnival and Other Christian Festivals: Folk Theology and Folk Performance", anarchy, Ash Wednesday, blesses, Bolivia, brutal, Candlemas, Carnival, celebrate, civil war, confined, connotation, delaying, demonic, devote, dictatorship, disorder, dragons, dreams, egalitarian, evidently, exploitation, express, external, festival, festive, forces, General Francisco Franco, generally, holiday, indigenous, La Paz, liberty, longer, Manresa, marginalized, Max Harris, migrated, miners, movable, MUSEF, Oruro, photographed, protest, restoration, Sanctuary of the Mineshaft, single, streets, subsequent, themselves, thousands, unmasking, Virgin of Socavon, Virgin of the Mineshaft

Pearls from artists* # 515

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

“Under [General Francisco] Franco,” he said, “attendance at Catholic holidays was obligatory and much Catalan folklore was banned. People avoided the religious processions and, once they were no longer mandatory, ignored them… Marvesa’s [Spain] festive license of demons and dragons is no longer of darkness. If Franco claimed the mantle of Catholic light, then to party as Catalan devils is a happy celebration of freedom.

Demons and dragons are a customary feature of saints’ days and Corpus-Christi festivals throughout Spain and its former empire. They are also common in Carnivals. Indeed, it is partly because of the presence of demons, dragons, and other masked transgressive figures that Carnival has been so often designated – by defenders and detractors alike – as a pagan or devilish season, a time of unrestrained indulgence before the ascetic penances of Lent.

Julio Caro Baroja, the father of Spanish Carnival studies, scorned the antiquarian notion that the masked figures and seasonal inversions of Carnival were “a mere survival” of ancient pagan rituals. Carnival, he argued, was first nurtured by the dualistic oppositions of Christianity. Where it survives – for when he wrote it had been banned by Franco – it still enacts these old antagonisms. “Carnival,” he concluded, “is the representation of paganism itself face-to-face with Christianity.”

... Peter Burke, one of the more lucid historians of popular culture, has proposed that “there is a sense in which every festival [in early modern Europe] was a miniature Carnival because it was an excuse for disorder and because it drew from the same repertoire of traditional forms.

Max Harris in Carnival and Other Christian Festivals: Folk Theology and Folk Performance

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2022, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes, Source Material

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 515

Tags: "The Orator", "Carnival and Other Christian Festivals: Folk Theology and Folk Performmance", aescetic, ancient, antagonisms, antiquarian, argued, attendance, avoided, banned, Carnivals, Catalan, Catholic, celebration, Christianity, claimed, common, Corpus-Christi, culture, customary, darkness, defenders, demons, designated, detractors, devilish, disorder, dragons, dualistic, empire, enacts, Europe, excuse, face-to-face, father, feature, festivals, festive, figures, folklore, former, Franco, freedom, historians, holidays, ignored, indulgence, inversions, itself, Julio Caro Baroja, license, longer, mandatory, mantle, Marvesa, masked, Max Harris, miniature, modern, nurtured, obligatory, oppositions, paganism, penances, people, Peter Burke, popular, presence, processions, proposed, religious, repertoire, representation, rituals, saints, sandpaper, scorned, season, seasonal, soft pastel on sandpaper, Spain, Spanish, studies, survival, survives, throughout, traditional, transgressive, unrestrained