Blog Archives

Q: Do you have any favorites among the Mexican and Guatemalan folk art figures that you depict in your work?

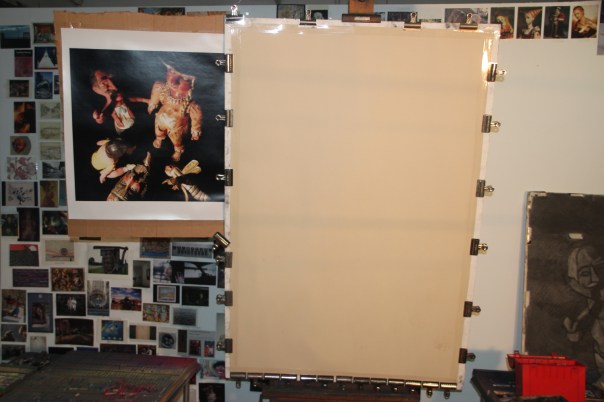

A: I suppose it seems that way, since I certainly paint some figures more than others. My favorite characters change, depending on what is happening in my work. My current favorites are a figure I have never painted before (the Balinese dragon above) and several Mexican and Guatemalan figures last painted years ago. All will make an appearance in a pastel painting for which I am still developing preliminary ideas (above).

Comments are welcome!

Q: Would you talk about how the Judas figures you depict in your pastel paintings function in Mexico?

A: Here’s a good explanation from a website called “Mexican Folk Art Guide”:

“La quema de Judas or the Judas burning in Mexico is a celebration held on Sabado de Gloria (Holy Saturday). Papier mache figures symbolizing Judas Iscariot stuffed with fireworks are exploded in local plazas in front of cheerful spectators.

The Judases exploded in public spaces can measure up to 5 meters, while 30 cm ones can be found with a firework in their back to explode at home.

In Mexico la quema de Judas dates from the beginning of the Spanish colony when the Judas effigies were made with hay and rags and burned. Later as paper became available and the fireworks techniques arrived, thanks to the Spanish commerce route from the Philippines, the Judases were made out of cardboard, stuffed with fireworks, and exploded.

After the Independence War the celebration lost its religious character and became a secular activity. The Judas effigies were stuffed with candies, bread, and cigarettes to attract the crowds into the business [establishment] that sponsored the Judas.

Judas was then depicted as a devil and identified with a corrupt official, or any character that would harm people. In 1849 a new law stipulated that it was forbidden to relate a Judas effigy with any person by putting a name on it or dressing it in a certain way to be identified with a particular person.”

This is why whenever I bring home a Judas figure from Mexico, I feel like I have rescued it from a fire-y death!

Comments are welcome!

Q: How long have you been working in your current studio?

A: I have been in my West 29th Street space for seventeen years, but from the beginning, in the mid-1980’s, I had a studio. My first one was in the spare bedroom of the Alexandria, Virginia, house that I shared with Bryan and that I still own. For about three years in the 1990s I had a studio on the third floor of the Torpedo Factory Art Center, a building in Alexandria that is open to the public. People come in, watch artists work, and occasionally buy a piece of art.

In April 997 an opportunity to move to New York arose and I didn’t look back. By then I was showing in a good 57th Street gallery, Brewster Arts Ltd. (the gallery focused exclusively on Latin American artists; I was thrilled with the company I was in; the only fellow non-Latina represented by owner, Mia Kim, was Leonora Carrington), and I had managed to find a New York agent, Leah Poller, with whom to collaborate. I looked at only one other space before finding my West 29th Street studio. An old friend of Bryan’s from Cal Tech rented the space next door and he had told us it was available. Initially the studio was a sublet. The lease-holder was a painter headed to northern California to work temporarily for George Lucas at the Lucas Ranch. After several years she decided to stay so I was able to take over the lease.

My studio continues to be an oasis in a chaotic city, a place to make art, to read, and to think. I love to walk in the door every morning and always feel more calm the moment I arrive. It’s my absolute favorite place in New York!

Comments are welcome!

Q: How do you select a photograph to use as reference material to make a pastel painting?

A: Like everything else associated with my studio practice, my use of photographs from which to work has changed considerably. Beginning in the early 1990s all of the paintings in my first series, “Domestic Threats,” started out as elaborately staged, well-lit scenes that either my husband, Bryan, or I photographed with Bryan’s Toyo Omega 4 x 5 view camera using a wide-angle lens. Depending on where I was living at the time, I set up the scenes in one of three places: our house in Alexandria, VA, a six-floor walkup apartment on West 13th Street in New York, or my current Bank Street condominium. Then one of us shot two pieces of 4 x 5 film at different exposures and I’d usually select the more detailed one to be made into a 20″ x 24″ photo to use as a reference.

Just as the imagery in my paintings has simplified and emptied out over the years, my creative process has simplified, too. I often wonder if this is a natural progression that happens as an artist gets older. More recently I have been shooting photos independently of how exactly I will use them in my work. Only later do I decide which ones to make into paintings; sometimes it’s YEARS later. For example, the pastel painting that is on my easel now is based on a relatively old (2002) photograph that I have always liked, but only now felt ready to tackle in pastel.

Comments are welcome!

Q: When and why did you start working on sandpaper?

A: In the late 1980s when I was studying at the Art League in Alexandria, VA, I took a three-day pastel workshop with Albert Handel, an artist known for his southwest landscapes in pastel and oil paint. I had just begun working with soft pastel (I’d completed my first class with Diane Tesler) and was still experimenting with paper. Handel suggested I try Ersta fine sandpaper. I did and nearly three decades later, I’ve never used anything else.

The paper (UArt makes it now) is acid-free and accepts dry media, especially pastel and charcoal. It allows me to build up layer upon layer of pigment, blend, etc. without having to use a fixative. The tooth of the paper almost never gets filled up so it continues to hold pastel. If the tooth does fill up, which sometimes happens with problem areas that are difficult to resolve, I take a bristle paintbrush, dust off the unwanted pigment, and start again. My entire technique – slowly applying soft pastel, blending and creating new colors directly on the paper (occupational hazard: rubbed-raw fingers, especially at the beginning of a painting as I mentioned in last Saturday’s blog post), making countless corrections and adjustments, looking for the best and/or most vivid colors, etc. – evolved in conjunction with this paper.

I used to say that if Ersta ever went out of business and stopped making sandpaper, my artist days would be over. Thankfully, when that DID happen, UArt began making a very similar paper. I buy it from ASW (Art Supply Warehouse) in two sizes – 22″ x 28″ sheets and 56″ wide by 10 yard long rolls. The newer version of the rolled paper is actually better than the old, because when I unroll it it lays flat immediately. With Ersta I laid the paper out on the floor for weeks before the curl would give way and it was flat enough to work on.

Comments are welcome!