Blog Archives

Q: What have you learned about the people of Mexico through your travels, reading, and research?

A: It didn’t take long to become smitten with these beautiful people. It happened on my first trip there in 1992 when Bryan and I, along with busloads of other tourists, were visiting the Oaxacan cemeteries on The Day of the Dead. The Oaxaquenos tending their ancestor’s graves were so dignified and so gracious, even with so many mostly-American tourists tromping around on a sacred night, that I couldn’t help being taken with them and with their beliefs. My studies since that time have given me a deeper appreciation for the art, architecture, history, mythology, etc. that comprise the extremely rich and complex story of Mexico as a cradle of civilization in the West. It is a wonderfully heady mix and hopefully some of it comes through in my work as a painter and a photographer.

By the way I often wonder why the narrative of Mexico’s fascinating history was not taught in American public schools, at least not where I went to public school in suburban New Jersey. Mexico is our neighbor, for goodness sake, but when I speak to many Americans about Mexico they have never learned anything about the place! It’s shocking, but many people think only “Spring Break” and/or “Drug Wars,” when they hear the word “Mexico.” As a kid I remember learning about Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and other early civilizations in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia, but very little about Mexico. We learned about the Maya, when it was still believed that they were a peaceful people who devoted their lives to scientific and religious pursuits, but that story was debunked years ago. And I am fairly sure that not many Americans even know that Maya still exist in the world … in Mexico and in Guatemala. There are a few remote places that were not completely destroyed by Spanish Conquistadores in the 16th century and later. I’ve been to Mayan villages in Guatemala and seen shamans performing ancient rituals. For an artist from a place as rooted in the present moment as New York, it’s an astounding thing to witness!

Comments are welcome!

Q: Your new work explores relationships to figures through the medium of soft pastel. What prompted this departure from photography?

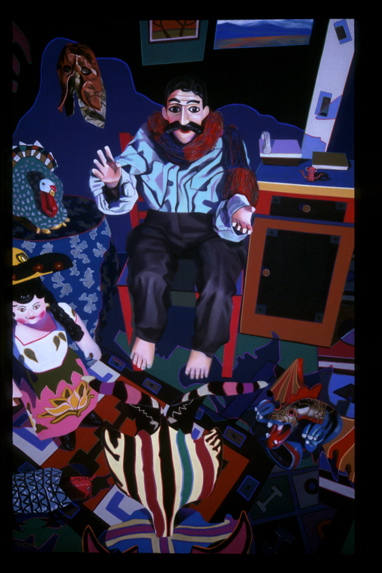

A: Actually it was the other way around. As I’ve mentioned, I was a maker of pastel-on-sandpaper paintings long before I became a photographer (1986 vs. 2002). However, the photos in the “Gods and Monsters” series were meant to be photographs in their own right, i.e., they were not made to be reference material for paintings. in an interesting turn of events, in 2007 I started a new series, “Black Paintings,” which uses the “Gods and Monsters” photographs as source material. Collectors who have been following my work for years tell me the new series is the strongest yet. For now I’m enjoying where this work is leading. The last three paintings are the most minimal yet and I’ve begun thinking of them as the “Big Heads.” There is usually a single figure (“Stalemate” has two) that is much larger than life size. “Epiphany” (above, left) is an example. All of them are quite dramatic when seen in person, especially with their black wooden frames and mats.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Is there an overarching narrative in your photographs with Mexican and Guatemalan figures?

A: Maybe, but that’s something for the viewer to judge. I never specify exactly what my work is about for a couple of reasons: my thinking about the meaning of my work constantly evolves, plus I wouldn’t want to cut off other people’s interpretations. Everything is equally valid. I heard Annie Leibovitz interviewed some time ago on the radio. She said that after 40 years as a photographer, everything just gets richer. It doesn’t get easier, it just gets richer. I’ve been a painter for 27 years, a photographer for 11, and I agree completely. Creating this work is an endlessly fascinating intellectual journey. I realize that I am only one voice in a vast art world, but I hope that through the ongoing series of questions and answers on my blog, I am conveying some sense of how artists work and think.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Can you speak in more detail about how losing your husband, Dr. Bryan C. Jack, on 9/11 affected your artistic practice?

“She Embraced It and Grew Stronger,” 2003, 58″ x 38″, first large pastel-on-sandpaper painting completed after Bryan was killed

A: On September 11, 2001, Bryan, who was a high-ranking, career, federal government employee, a brilliant economist (with an IQ of 180 he is still the smartest man I’ve ever met) and a budget analyst at the Pentagon, was en route to Monterrey, CA to give his monthly guest lecture for an economics class at the Naval Postgraduate College there. He had the horrible misfortune of flying out of Dulles airport and boarding the plane that was high-jacked and crashed into the Pentagon, killing 189 people.

Losing him was the biggest shock of my life, devastating in every possible way. I think about him every day and I continually think about how easily I, too, could have been killed on 9/11. I had decided not to travel with Bryan to California, a place I absolutely love visiting, only because the planned trip was too short. His plane crashed directly into my (Navy Reserve) office on the fifth floor, e-ring of the Pentagon. I still imagine how close we came to Bryan having been killed on the plane and me perishing in the building. To this day I believe that I was spared for a reason and I strive to make every day count.

The six months after 9/11 passed by in a blur, except that I vividly remember an October 2001 awards ceremony at the DAR Hall in Washington, DC. I was picked up by a big black limousine, sent by the Department of Defense. At the ceremony I sat with members of the president’s cabinet. I accepted the Defense Exceptional Civilian Service Medal for Bryan, an award he would have accepted himself had he been alive, and was addressed face-to-face by George Bush, Jr., not someone I particularly liked (to put it nicely). Later Bryan was given more awards – a Presidential Rank Award, a Defense Distinguished Civilian Service Medal, and the Defense of Freedom Medal. Many other honors came in and I’ll mention two. Bryan’s hometown of Tyler, Texas named a magnet school after him – Dr. Bryan C. Jack Elementary School (the principal and I cut the ribbon at the opening ceremony) – and Stanford University set up the “Bryan Jack Memorial Scholarship,” which annually helps two deserving students attend Stanford Business School.

The following summer I was ready to – I HAD to – get back to work so my first challenge was to learn how to use Bryan’s 4 x 5 view camera. In July 2002 I enrolled in a one-week view camera workshop at the International Center of Photography in New York. Much to my surprise I already knew quite a lot from watching Bryan. Thankfully, I was soon on my way to working again. After the initial workshop, I decided to begin with the basics since I had never formally studied photography before. I threw myself into learning this new (to me) medium. Over the next few years I enrolled in a series of classes at ICP, starting with Photography I. Along the way I learned to use Bryan’s extensive camera collection (old Leicas, Nikons, Mamiyas, and more) and to make my own large chromogenic prints in the darkroom. In October 2009 it was extremely gratifying to have my first solo photography exhibition with HP Garcia in New York (please see the exhibition catalogue on the sidebar). I remember tearing up at the opening as I imagined Bryan looking down at me with his beautiful smile, beaming as he surely would have, so proud of me for having become a photographer.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 21

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

It is the beginning of a work that the writer throws away.

A painting covers its tracks. Painters work from the ground up. The latest version of a painting overlays earlier versions, and obliterates them. Writers, on the other hand, work from left to right. The discardable chapters are on the left. The latest version of a literary work begins somewhere in the work’s middle, and hardens toward the end. The earlier version remains lumpishly on the left; the work’s beginning greets the reader with the wrong hand. In those early pages and chapters anyone may find bold leaps to nowhere, read the brave beginnings of dropped themes, hear a tone since abandoned, discover blind alleys, track red herrings, and laboriously learn a setting now false.

Several delusions weaken the writer’s resolve to throw away work. If he has read his pages too often, those pages will have a necessary quality, the ring of the inevitable, like poetry known by heart; they will perfectly answer their own familiar rhythms. He will retain them. He may retain those pages if they possess some virtues, such as power in themselves, though they lack the cardinal virtue, which is pertinence to, and unity with, the book’s thrust. Sometimes the writer leaves his early chapters in place from gratitude; he cannot contemplate them or read them without feeling again the blessed relief that exalted him when the words first appeared – relief that he was writing anything at all. That beginning served to get him where he was going, after all; surely the reader needs it, too, as groundwork. But no.

Every year the aspiring photographer brought a stack of his best prints to an old, honored photographer, seeking his judgment. Every year the old man studied the prints and painstakingly ordered them into two piles, bad and good. Every year the old man moved a certain landscape print into the bad stack. At length he turned to the young man: “You submit this same landscape every year, and every year I put it in the bad stack. Why do you like it so much?” The young photographer said, “Because I had to climb a mountain to get it.”

Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Comments are welcome!