Blog Archives

Q: You take 3-4 months to complete one artwork. How do you plan a series such as Bolivianos over a year’s timeline and over the years? (Question from Vedica Art Studios and Gallery)

A: Bolivianos is my third series, and like the previous two, it naturally evolves from one painting to the next. There wasn’t a long-term plan involved, and I doubt such detailed planning would even be practical. Many artists likely work this way—finishing one project and then beginning another. As with Bolivianos, I typically have ideas for the next two or three paintings, but little concept beyond that.

The main impetus for Bolivianos was to continue work I began in the early 1990s. During a visit to La Paz, I captured a series of stunning photographs, inspiring me to translate them into a major pastel series. Each painting leads to ideas about the next, guiding the entire series’ evolution and shaping my understanding of its meaning. Both the series and my insights deepen as I engage further with the subject matter. The Bolivian Carnival masks I photographed provided the starting point for a long and continuing intellectual journey.

Comments are welcome!

Q: How do you decide when a pastel painting is finished?

“Magisterial,” soft pastel on sandpaper, 58” x 38” in progress

A: During the months that it takes to create a pastel painting, I search for arresting colors that work well together. The goal is to make a painting that I have never seen before and that leads the viewer’s eyes around in interesting ways. To do this I build up and blend together as many as 25 to 30 layers of pigment. I am able to complete some areas, like the background, fairly easily – maybe with just six or seven layers of black Rembrandt pastel. The more realistic parts of a pastel painting take many more applications. In general, details always take plenty of time to refine and perfect.

No matter how many pastel layers I apply, however, I never use fixatives. It is difficult to see this in reproductions of my work, but some of the finished surfaces achieve a texture akin to velvet. My technique involves blending each layer with my fingers, pushing the pastel deep into the tooth of the sandpaper, and mixing new colors directly on the paper. Fortunately, the sandpaper holds plenty of pigment so I am able to include lots of details.

Before I pronounce a pastel painting finished, I let it sit against a wall in my studio for a few days so I can look at it later with fresh eyes. I consider a piece done when it is as good as I can make it, when adding or subtracting something would diminish what is there. Always, I try to push myself and my materials to their limits, using them in new and unexpected ways.

Comments are welcome.

Q: How do you decide when a pastel painting is finished?

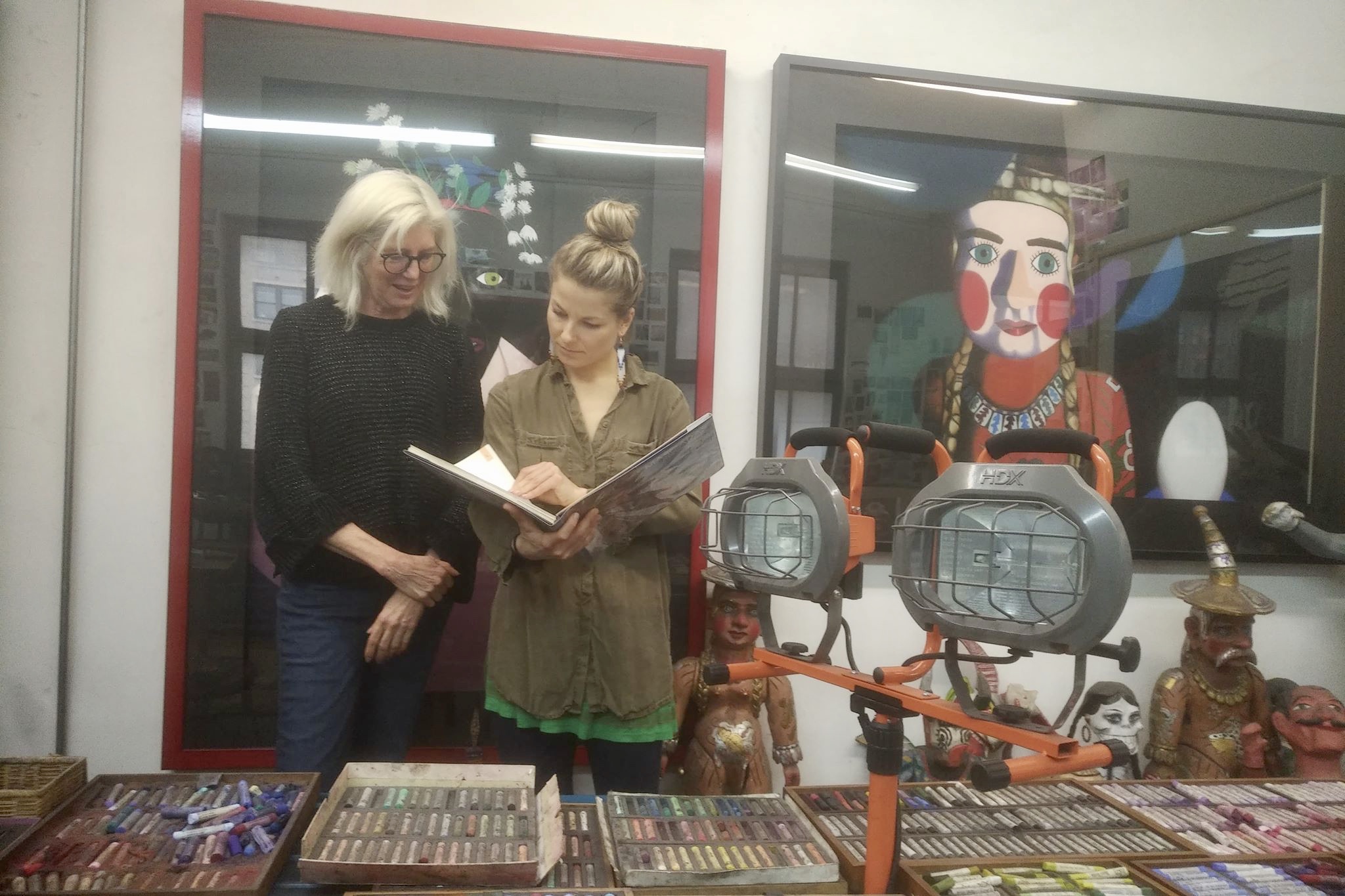

Signing “Apparition,” soft pastel on sandpaper, 58” x 38”

A: During the several months that I work on a pastel painting, I search for the best, most eye-popping colors, as I build up and blend together as many as 25 to 30 layers of pigment. I am able to complete some areas, like the background, fairly easily – maybe with six or seven layers – but the more realistic parts take more applications because I am continually refining and adding details. Details always take time to perfect.

No matter how many pastel layers I apply, however, I never use fixatives. It is difficult to see this in reproductions of my work, but the finished surfaces achieve a texture akin to velvet. My technique involves blending each layer with my fingers, pushing pastel deep into the tooth of the sandpaper. The paper holds plenty of pigment and because the pastel doesn’t flake off, there is no need for fixatives.

I consider a given painting complete when it is as good as I can make it, when adding or subtracting anything would diminish what is there. I know my abilities and I know what each individual stick of pastel can do. I continually try to push myself and my materials to their limits.

Comments are welcome.

Q: Have you always signed your work on the front? (Question from Anna Rybat)

A: Yes, I have no other choice. I frame all of my pastel paintings under plexiglas soon after they’re completed. Were I to sign on the reverse, as do many painters, my signature would be hidden. Moreover, I sign using pastel pencils so the letters would get smudged.

As I compose and work to complete a pastel painting, I reserve a specific location for my signature. I sign discreetly so as not to interfere with the depicted imagery. In most cases you have to look closely to see my name.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 428

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

In its spectacle and ritual the Carnival procession in Oururo bears an intriguing resemblance to the description given by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega of the great Inca festival of Inti Raymi, dedicated to the Sun. Even if Oururo’s festival did not develop directly from that of the Inca, the 16th-century text offers a perspective from the Andean tradition:

“The curacas (high dignitaries) came to their ceremony in their finest array, with garments and head-dresses richly ornamented with gold and silver.

Others, who claimed to descend from a lion, appeared, like Hercules himself, wearing the skin of this animal, including its head.

Others, still, came dressed as one imagines angels with the great wings of the bird called condor, which they considered to be their original ancestor. This bird is black and white in color, so large that the span of its wing can attain 14 or 15 feet, and so strong that many a Spaniard met death in contest with it.

Others wore masks that gave them the most horrible faces imaginable, and these were he Yuncas (people from the tropics), who came to the feast with the heads and gestures of madmen or idiots. To complete the picture, they carried appropriate instruments such as out-of-tune flutes and drums, with which they accompanied the antics.

Other curacas in the region came as well decorated or made up to symbolize their armorial bearings. Each nation presented its weapons: bows and arrows, lances, darts, slings, maces and hatchets, both short and long, depending upon whether they used them with one hand or two.

They also carried paintings, representing feats they had accomplished in the service of the Sun and of the Inca, and a whole retinue of musicians played on the timpani and trumpets they had brought with them. In other words, it may be said that each nation came to the feast with everything that could serve to enhance its renown and distinction, and if possible, its precedence over the others.”

El Carnaval de Oruro by Manuel Vargas in Mascaras de los Andes Bolivianos, Editorial Quipus and Banco Mercantil

Comments are welcome!