Blog Archives

Q: What’s the most unusual place you have exhibited your art? Was it worth it?

A: In 2004 I exhibited in a group show that was hosted as a fund raiser for Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Artists who had had breast cancer were invited to present our work. The show was titled, “Art of Survival,” and was held in a breast surgeon’s office in West Long Branch, NJ. I had absolutely no expectations of selling anything and reluctantly participated, thinking, “More people are likely to see my work in this show than would see it in my studio during the same period.” Who could have foreseen it, but I sold a $15,000 painting to the surgeon who had organized the exhibition!

Sadly, several years later, the curator of the exhibition informed me that Beth, the breast cancer surgeon, had died from the same disease.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 672

Barbara’s Studio

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Beware of first impressions; try to have more presence of mind.

You should not be deceived by the eager promises of your best friends, by offers of help from influential people, or by the interest which men of talent seem to take in you, into thinking that there is anything real in what they say – real in the way of results, I mean. Many people are full of good intentions when they speak, but their eagerness subsides appreciably when it comes to action, like blusterers, or people who make angry scenes […]. And you, yourself, try to be more cautious in the way you welcome people, and above all, avoid these ridiculous attentions; they’re only offered on the impulse of the moment.

Cultivate a well-ordered mind, it’s your only road to happiness; and to reach it, be orderly in everything, even in the smallest details.

The Journal of Eugène Delacroix, edited by Hubert Wellington

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 660

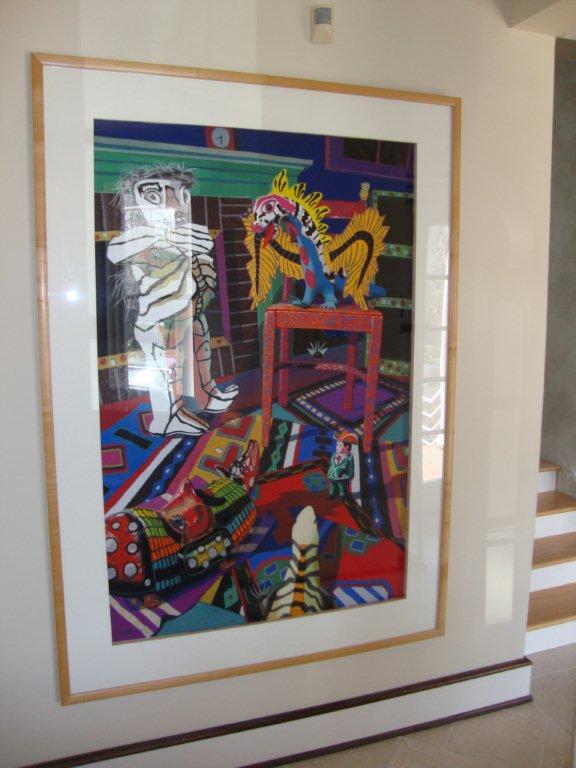

Dropping off “Harbinger” at the framer!

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

While most citizens sell precious life hours to procure money, those who acquire the most wealth spend that money to buy more free time. Billionaire CEOs turf tasks to upper-level managers to free themselves for blocks of uninterrupted learning and creative thinking time, because this is how earth-shattering, paradigm-blending breakthroughs are cultivated (Simmons, 2017). Our world is rapidly dividing into two groups: those who allow their time and focus to be constantly manipulated by others, and those who seize control of how they spend their short time on earth.

Kate Kretz in Art From your Core: A Holistic Guide to Visual Voice

Comments are welcome!

Q: Did you formally study art? (Question from “Cultured Focus Magazine”)

A: My bachelor’s degree in Psychology is from the University of Vermont. I did not formally study art, unless you want to count the several years-worth of drawing and painting classes I took at the Art League School in Alexandria, VA. I never went to art school so do not have a bachelor’s or master’s degree in art.

Much later, in the early 2000s, I was compelled to study photography at the International Center of Photography in New York. This is a rather long story.

On September 11, 2001, my husband Bryan Jack, a high-ranking federal government employee, a brilliant economist and a budget analyst at the Pentagon, was on his way to present his monthly guest lecture in economics at the Naval Postgraduate College in Monterey, CA. He was a passenger on the plane that departed from Dulles Airport and was high-jacked and crashed into the Pentagon.

Losing Bryan on 9/11 was the biggest shock of my life, devastating in every way imaginable. We were soulmates and newly married. I have lived with his loss every single day for more than twenty years now. Life has never been the same.

In the summer of 2002 I was beginning to feel ready to get back to work. Learning about photography and cameras became essential avenues to my well-being.

My first challenge was learning how to use Bryan’s 4 x 5 view camera. Bryan had always taken the 4 x 5 negatives from which I derived the reference photos that were essential tools for making pastel paintings. I enrolled in a one-week view camera workshop at the International Center of Photography in New York. Surprisingly, it was very easy. I had derived substantial technical knowledge just from watching Bryan for many years.

After the view camera workshop, I decided to throw myself into learning this new medium, beginning with Photography I. I spent the next few years taking many classes at ICP and learning as much as I could. Eventually, I learned how to use Bryan’s extensive collection of film cameras, to properly light the setups that served as subject material for my “Domestic Threats” pastel paintings, and to make my own large chromogenic prints in a darkroom.

Then in October 2009 I was invited to present a solo photography exhibition at a gallery in New York. Continuing to make art after Bryan’s death had seemed like such an impossibility. I remember thinking how proud he would have been to know I became a good photographer.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 631

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

I could see motion when I looked at Julie’s work. Her hand had moved there, in that way. She’d chosen this blue over that one. Seeing the act of creation – the way a work doesn’t come out fully formed but grows by fits and starts – made we aware of how delicate and fragile an artwork was. How improbable it was that it existed. Someone had agonized over this square inch. They’d poured themselves into that flink of a line. I thought of the bewildering piles of supplies I’d seen in studios: Vaseline, turpentine, wax, Q-tips, chopsticks, marble dust. It’s not magic that makes a piece. All the Hollywood visions of possessed artists throwing pieces together in a trance-like state overlooked the fact that this was work. Each piece may have started with an idea, but there was more to it than that. “An idea is not a painting,” Julie said, as she worked, her nose practically grazing the canvas. She was already thinking ahead to how she’d fix the brushyness of the tights, maybe go over the shoes again. The soul of the artwork needed a body. Seeing Julie work gave me a path to follow into the piece.

Bianca Bosker in Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See

Comments are welcome!

Q: What kind of internal conversations do you tend to have when you are in the process of making art? (Question from Vedica Art Studios and Gallery)

Jan 10

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

A: When standing at my easel creating a pastel painting, I focus on formal properties: composition, shape, color, and line. I always strive to produce a painting I’ve never seen before. Even as (perhaps especially as) the creator, I want to be surprised by the final result. My studio days are spent thinking, looking, reacting, and adjusting colors and composition as I refine increasingly tiny details, ensuring all elements work harmoniously. I determine which areas need to recede or advance, which require intricate details to appear three-dimensional, and which are better left as flat areas of color.

These countless adjustments ensure viewers’ eyes are guided around the finished painting in intriguing ways. I often recall something collectors of my pastel paintings shared: they mentioned a New York Times review of a Nan Goldin exhibition, in which the writer stated, “All of the pleasure circuits are fired in looking.” The collectors agreed this is exactly how they feel when viewing my work. Artists live for appreciative comments like these!

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

Posted in 2026, An Artist's Life, Creative Process, Studio, Working methods

Leave a comment

Tags: adjusting, adjustments, advance, agreed, always, appear, appreciative, areas, around, artists, “Magisterial”, “New York Times”, better, circuits, collectors, colors, comments, composition, countless, creating, creator, details, determine, elements, ensure, ensuring, especially, exactly, exhibition, finished, fired, formal, guided, harmoniously, increasingly, intricate, intriguing, looking, mentioned, Nan Goldin, painting, pastel painting, perhaps, pleasure, produce, properties, question, reacting, recall, recede, refine, require, result, review, shared, something, stated, strive, Studio, surprised, thinking, three-dimensional, Vedica Art Studios and Gallery, viewers, viewing, working, writer