Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 690

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

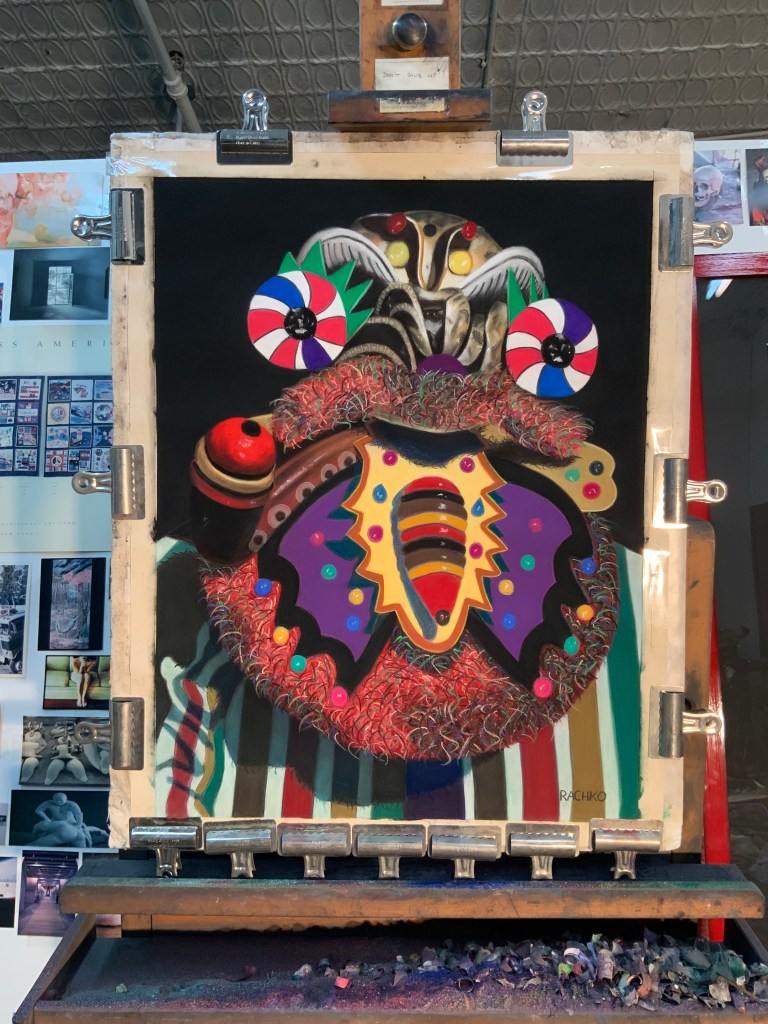

“Showman,” soft pastel on sandpaper, 26” x 20”

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

PC: And today, don’t you think a picture communicates primarily through its metiére? A mysterious transubstantiation takes place between the thing itself and the way in which our eye receives it. Or, more precisely, a painter’s metiére has life in it, as if it were still laden with the artist’s passion. You feel his pulse beating in it, his need to register the victory of his presence in physical space but outside the reach of time.

HM: Every painter with real talent has his own metiére, a way of laying on the paint with relish, with a certain voluptuous feel, which means that you could say that metiére of this or that painter is like velvet, or satin, or taffeta. As to manner… No one knows where this comes from. It’s magic. It’s not something you can learn. There are very rich paintings, like those of Cézanne, and others very lightly painted that have real density all the same: Velazquez, for example, with his Phillip IV. He uses a scumble for the landscape, which is very beautiful and solid with matiére—the scumble is so well proportioned that it combines with the background and harmonizes perfectly; the Rubens painting on wood in the Louvre, Portrait of Hélène Fourmont and Her Children, is painted mainly in colored oils, yet how deep and solid the colors seem!

Chatting with Henri Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview, Henri Matisse and Pierre Courthion, edited by Serge Guilbaut

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2026, Art in general, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes

Tags: “Chatting with Henri Matisse: The lost 1941 Interview”, “Showman”, background, beating, beautiful, Cézanne, certain, colored, combines, communicates, density, example, harmonizes, Henri Matisse, itself, landscape, laying, lightly, Louvre, mainly, manner, metiére, mysterious, others, outside, painted, painter, painting, passion, perfectly, Phillip IV, physical, picture, Pierre Courthion, Portrait of Hélène Fourmont and Her Children, precisely, presence, primarily, proportioned, receives, register, relish, Rubens, satin, scumble, Serge Guilbaut, soft pastel on sandpaper, something, taffeta, transubstantiation, Velazquez, velvet, victory, voluptuous

Q: You read books on Friedrich Nietzsche and other philosophers. How has philosophy and your personal experience shaped the latest series, Bolivianos? (Question from Vedica Art Studios and Gallery)

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

A: It’s difficult to pinpoint how philosophy specifically shaped my work because my curiosity spans so many subjects. Some critics have described me as a Renaissance woman, remarking on my wide-ranging and voracious reading. It’s true—I’m genuinely interested in practically everything!

In pursuit of making art, I have undertaken in-depth studies of numerous intriguing fields: drawing, color, composition, gross anatomy, art and art history, the art business, film history, photography, psychology, mythology, literature, philosophy, religion, music, jazz history, and archaeology—particularly ancient Mesoamerica (Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Aztec, and Maya) and South America (the Inca and their ancestors).

Since the early 1990s, my inspiration and subject matter have come primarily from international travel to remote parts of the globe, especially Mexico, Central America, and South America. Travel is by far the best education! By visiting distant destinations, I have developed a deep reverence for people and cultures around the world. People everywhere are connected by our shared humanity.

These travels, supplemented by extensive research at home, are essential parts of my creative process. Research can be solitary and demanding, but I truly enjoy it. I want to know as much as possible, and this curiosity generates ideas for new work, propelling me into unexplored creative realms.

Foreign travel always expands our ways of thinking. This rich mixture of creative influences continually evolves and finds its way into my pastel paintings. Working, learning, evolving, and growing—I am perpetually curious and can hardly imagine a better way to spend my time on Earth!

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2026, An Artist's Life, Bolivianos, Creative Process, Inspiration, Photography, Teleidoscope, Travel

Tags: ancestors, ancient, Andes, archaeology, around, Art Business, art history, Aztec, better, Bolivianos, Central America, composition, connected, continually, creative, creative process, critics, cultures, curiosity, demanding, described, destinations, developed, difficult, distant, drawing, education, especially, essential, everything, everywhere, evolves, evolving, expands, experience, extensive, fields, film history, final approach, Friedrich Nietzsche, generates, genuinely, gross anatomy, growing, hardly, humanity, imagine, in-depth, Inca, influences, inspiration, interested, international, intriguing, jazz history, La Paz, latest, learning, literature, making art, Maya, Mesoamerica, Mexico, Mixtec, mixture, mythology, numerous, Olmec, particularly, pastel paintings, people, perpetually, personal, philosophers, philosophy, photography, pinpoint, possible, primarily, propelling, psychology, pursuit, question, reading, realms, religion, remarking, remote, Renaissance woman, research, reverence, series, shaped, shared, solitary, South America, specifically, studies, subject matter, subjects, supplemented, thinking, travel, undertaken, unexplored, Vedica Art Studios and Gallery, visiting, voracious, wide-ranging, working, Zapotec

Q: When did you begin drawing and painting? (Question from “Cultured Focus Magazine”)

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

A: This is a long story because my path to becoming a professional artist has been unusually circuitous.

I grew up in a blue collar family in suburban New Jersey. My parents were both first-generation Americans and no one in my family had gone to college. I was a smart kid, who showed some artistic talent in kindergarten and earlier. At the age of 6, my sister, my cousin, and I enrolled in Saturday morning painting classes at the studio of a local artist. I continued the classes for about 8 years and became a fairly adept oil painter.

At the age of 15 my father decided that art was not a serious pursuit – he called it a hobby, not a profession – and abruptly stopped paying for my Saturday morning lessons. Unfortunately, there were no artists or suitable role models in my family. So with neither financial nor moral support to pursue art, I turned my attention to very different interests.

Cut to ten years later. When I was 25, I earned my private pilot’s license and spent the next two years amassing other flying licenses and ratings, culminating in a Boeing-727 flight engineer’s certificate.

At 29, I joined the Navy. By then I was an accomplished civilian pilot with thousands of flight hours so I expected to fly jets. However, in the early 1980s women were not allowed in combat. There were very few women Navy pilots and those few were restricted to training male pilots. There were no women pilots landing on aircraft carriers.

In the mid-1980s I was in my early 30s, a lieutenant on active duty in the Navy, working a soul-crushing job as a computer analyst on the midnight shift in a Pentagon basement. It was literally and figuratively the lowest point of my life. I was completely bored and miserable.

Remembering the joyful Saturdays of my youth when I had taken art classes with a local New Jersey painter, I enrolled in a drawing class at the Art League School in Alexandria, Virginia. Initially I wasn’t very good, but it was wonderful to be around other women and a world away from the mentality of the Pentagon. I was having fun again! I enrolled in more classes and became a very motivated full-time art student who worked nights at the Pentagon. As I studied and improved my skills, I quickly discovered my preferred medium – soft pastel on sandpaper.

Although I knew I had found my calling, for more than a year I agonized over whether or not to leave the financial security of a Navy paycheck. Finally I did make up my mind and resigned my commission, effective on September 30, 1989. With Bryan’s (my then boyfriend’s) support, I left the Navy to devote my time to making art.

I’m probably one of the few people who can name THE day I became a professional artist! That day was October 1, 1989. Fortunately, I have never needed another job. I remained in the Navy Reserve for the next 14 years, working primarily at the Pentagon for two days each month and two weeks each year. I commuted by train to Washington, DC after I moved to Manhattan in 1997. Finally on November 1, 2003, I officially retired as a Navy Commander.

Life as a self-employed professional artist is endlessly varied, fulfilling, and interesting. I have never regretted my decision to pursue art full-time.

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in 2024, An Artist's Life, Inspiration

Comments Off on Q: When did you begin drawing and painting? (Question from “Cultured Focus Magazine”)

Tags: abruptly, accomplished, active duty, agonized, aircraft carriers, Alexandria, allowed, amassing, Americans, another, around, Art League School, artist, artistic, attention, “Cultured Focus Magazine”, became, becoming, blue collar, Boeing-727, boyfriend, called, calling, certificate, circuitous, civilian pilot, classes, college, combat, commission, commuted, completely, computer analyst, continued, cousin, culminating, decided, decision, devote, different, discovered, drawing, drawing class, earlier, earned, effective, endlessly, enrolled, expected, family, father, figuratively, finally, financial, financial security, first-generation, flight engineer, Flying, fulfilling, full-time, improved, initially, interesting, interests, joined, joyful, kindergarten, landing, lessons, licenses, lieutenant, literally, lowest, making, male pilots, Manhattan, medium, mentality, midnight shift, miserable, morning, motivated, Navy Commander, Navy Reserve, needed, neither, New Jersey, November 1 2003, October 1 1989, officially, oil painter, painting, parents, paycheck, paying, Pentagon, preferred, primarily, private pilot’s license, probably, profession, professional artist, pursue, pursuit, quickly, ratings, regretted, remained, remembering, resigned, restricted, retired, role models, Saturday, self-employed, September 30 1989, serious, showed, sister, soft pastel on sandpaper, soul-crushing, stopped, student, studied, Studio, suburban, support, talent, thousands, training, turned, unfortunately, unusually, varied, Virginia, Washington DC, whether, wonderful, worked, working

Pearls from artists* # 441

Posted by barbararachkoscoloreddust

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The most perennially popular category of art is the cheerful, pleasant, and pretty kind: meadows in spring, the shade of trees on hot summer days, pastoral landscapes, smiling children. This can be deeply troubling to people of taste and intelligence.

… The worries about prettiness are twofold. First, pretty pictures are alleged to feed sentimentality. Sentimentality is a symptom of insufficient engagement with complexity, by which one really means problems. The pretty picture seems to suggest that in order to make life nice, one merely has to brighten up the apartment with a depiction of some flowers. If we were to ask the picture what is wrong with the world, it might be taken as saying ‘You don’t have enough Japanese water gardens’ – a response that appears to ignore all the more urgent problems that confront humanity (primarily economic, but also moral, political, and sexual). The very innocence and simplicity of the picture seems to mitigate against any attempt to improve life as a whole. Secondly, there is the related fear that prettiness will numb us and leave us insufficiently critical and alert to the injustices surrounding us.

Alain de Botton and John Armstrong in Art as Therapy

Comments are welcome!

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Posted in Art in general, Inspiration, Pearls from Artists, Quotes, Studio

Comments Off on Pearls from artists* # 441

Tags: against, Alain de Botton, alleged, apartment, appears, Art as Therapy, attempt, brighten, category, cheerful, children, complexity, confront, critical, deeply, depiction, economic, engagement, enough, flowers, humanity, ignore, improve, injustices, innocence, insufficient, insufficiently, intelligence, Japanese, John Armstrong, landscapes, meadows, merely, mitigate, pastoral, people, perennially, picture, pleasant, political, popular, prettiness, primarily, problems, really, related, response, saying, sentimentality, sexual, simplicity, smiling, suggest, summer, surrounding, symptom, troubling, twofold, urgent, water gardens, worries