Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 635

Dinard, Brittany, France

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The body of writing takes a thousand different forms,

and there is no right way to measure.

Changing, changing at the flick of a hand, its various

forms are difficult to capture.

Words and phrases compete with one another, but the

mind is still master.

Caught between the unborn and the living, the writer

struggles to maintain both depth and surface.

He may depart from the square, he may overstep the

circle, searching for the one true form of his reality.

He would fill the eyes of his readers with splendor, he

would sharpen the mind’s values.

The one whose language is muddled cannot do it;

only when mind is clear can language be noble.

Lu Chi quoted in Free Play: Improvisation in Art and Life by Stephen Nachmanovitch

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 631

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

I could see motion when I looked at Julie’s work. Her hand had moved there, in that way. She’d chosen this blue over that one. Seeing the act of creation – the way a work doesn’t come out fully formed but grows by fits and starts – made we aware of how delicate and fragile an artwork was. How improbable it was that it existed. Someone had agonized over this square inch. They’d poured themselves into that flink of a line. I thought of the bewildering piles of supplies I’d seen in studios: Vaseline, turpentine, wax, Q-tips, chopsticks, marble dust. It’s not magic that makes a piece. All the Hollywood visions of possessed artists throwing pieces together in a trance-like state overlooked the fact that this was work. Each piece may have started with an idea, but there was more to it than that. “An idea is not a painting,” Julie said, as she worked, her nose practically grazing the canvas. She was already thinking ahead to how she’d fix the brushyness of the tights, maybe go over the shoes again. The soul of the artwork needed a body. Seeing Julie work gave me a path to follow into the piece.

Bianca Bosker in Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 488

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

To be astonished is to be caught unawares by the revelation of realities denied or repressed in the everyday. Astonishment has an intellectual as well as an emotional component – in it, the brain and the heart come together. Far from distracting us from the strange and the uncanny in life, the astonishment evoked by great artistic works puts them square in our sights. The work demands that we feel and think the mystery of our passage through this body, on this earth, in this universe. We realize afterward that the world is not what we thought it was: something hidden, impossible to communicate though clearly expressed in the work has risen into the light of awareness, and the share of the Real to which we are privy is proportionately expanded.

JF Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Q: Can you talk a little bit about your process? What happens before you even begin a pastel painting?

A: My process is extremely slow and labor-intensive.

First, there is foreign travel – often to Mexico, Guatemala or someplace in Asia – to find the cultural objects – masks, carved wooden animals, paper mâché figures, and toys – that are my subject matter. I search the local markets, bazaars, and mask shops for these folk art objects. I look for things that are old, that look like they have a history, and were probably used in religious festivals of some kind. Typically, they are colorful, one-of-a- kind objects that have lots of inherent personality. How they enter my life and how I get them back to my New York studio is an important part of my art-making practice.

My working methods have changed dramatically over the nearly thirty years that I have been an artist. My current process is a much simplified version of how I used to work. As I pared down my imagery in the current series, “Black Paintings,” my creative process quite naturally pared down, too.

One constant is that I have always worked in series with each pastel painting leading quite naturally to the next. Another is that I always set up a scene, plan exactly how to light and photograph it, and work with a 20″ x 24″ photograph as the primary reference material.

In the setups I look for eye-catching compositions and interesting colors, patterns, and shadows. Sometimes I make up a story about the interaction that is occurring between the “actors,” as I call them.

In the “Domestic Threats” series I photographed the scene with a 4″ x 5″ Toyo Omega view camera. In my “Gods and Monsters” series I shot rolls of 220 film using a Mamiya 6. I still like to use an old analog camera for fine art work, although I have been rethinking this practice.

Nowadays the first step is to decide which photo I want to make into a painting (currently I have a backlog of photographs to choose from) and to order a 19 1/2″ x 19 1/2″ image (my Mamiya 6 shoots square images) printed on 20″ x 24″ paper. They recently closed, but I used to have the prints made at Manhattan Photo on West 20th Street in New York. Now I go to Duggal. Typically I have in mind the next two or three paintings that I want to create.

Once I have the reference photograph in hand, I make a preliminary tonal charcoal sketch on a piece of white drawing paper. The sketch helps me think about how to proceed and points out potential problem areas ahead.

Only then am I ready to start actually making the painting.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 115

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

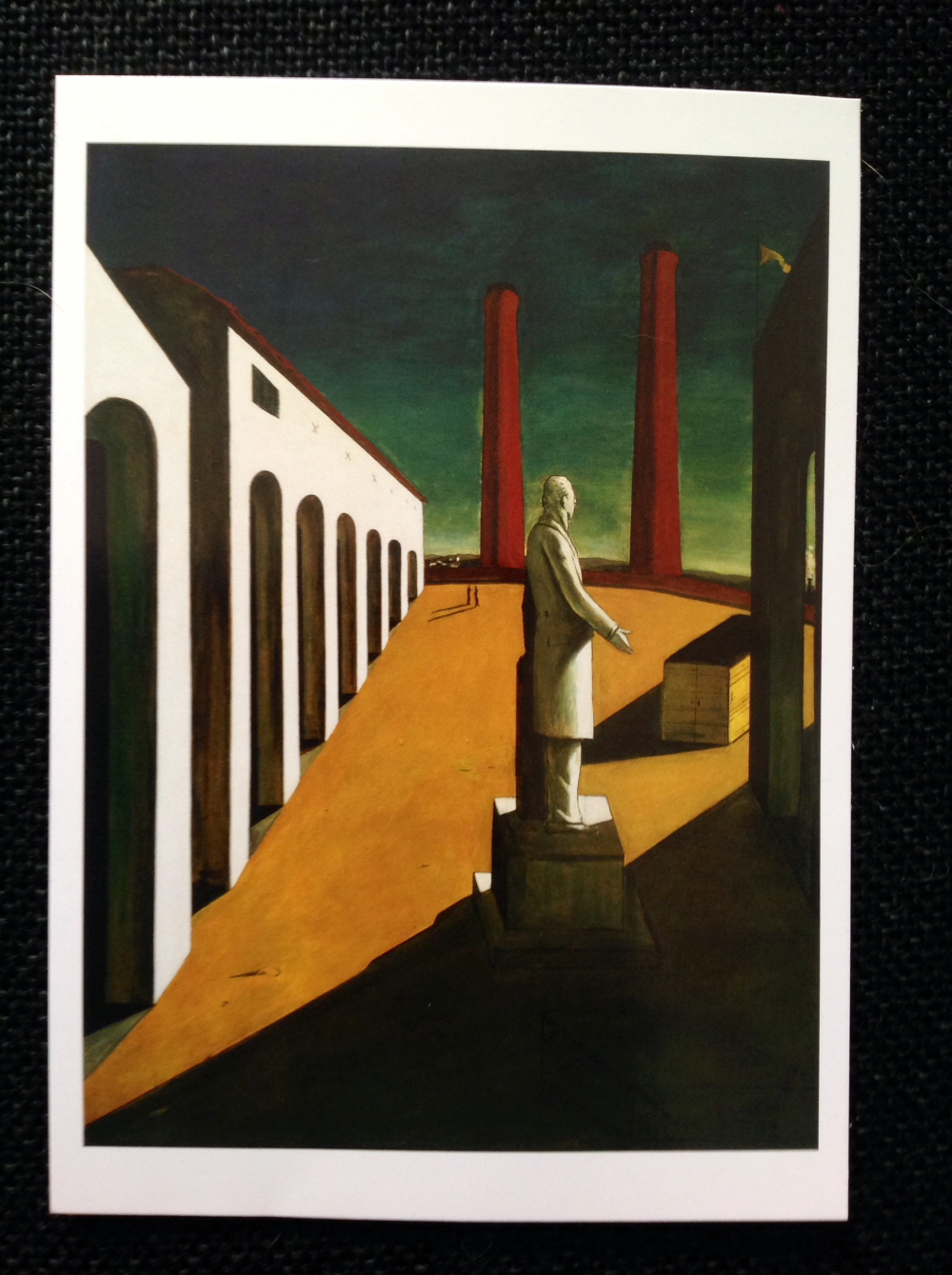

THE DISQUIETING MUSES

From Two de Chiricos

[On Giorgio de Chirico]

Boredom sets in first, and then despair.

One tries to brush it off. It only grows.

Something about the silence of the square.

Something is wrong; something about the air,

It’s color; about the light, the way it goes.

Something about the silence of the square.

The muses in their fluted evening wear,

Their faces blank, might lead one to suppose

Something about the silence of the square.

Something about the buildings standing there.

But no, they have no purpose but to pose.

Boredom sets in first, and then despair.

What happens after that, one doesn’t care.

What brought one here – the desire to compose

Something about the silence of the square.

Or something else, of which one’s not aware,

Life itself, perhaps – who really knows?

Boredom sets in first and then despair…

Something about the silence of the square.

Mark Strand in Art and Artists: Poems, edited by Emily Fragos

Comments are welcome!

Q: What does your creative process look like when you are ready to begin a new painting?

A: My working methods have changed dramatically over the years with my current process being a much-simplified version of how I used to work. In other words as I pared down my imagery in the “Black Paintings,” my process quite naturally pared down, too.

One constant is that I have always worked in series with each pastel painting leading quite logically to the next. Another is that I always have set up a scene, lit and photographed it, and worked with a 20″ x 24″ photograph as the primary reference material. In the “Domestic Threats” series I shot with a 4″ x 5″ view camera. Nowadays the first step is to decide which photo I want to make into a painting (currently I have a backlog of images to choose from) and to order a 19 1/2″ x 19 1/2″ image (my Mamiya 6 shoots square images and uses film) printed on 20″ x 24″ paper. I get the print made at Manhattan Photo on West 20th Street in New York. Typically I have in mind the next two or three paintings that I want to create.

Once I have the reference photograph in hand, I make a preliminary tonal charcoal sketch on a piece of white drawing paper. The sketch helps me think about how to proceed and points out potential problem areas ahead. For example, in the photograph above I had originally thought about creating a vertical painting, but changed to horizontal format after discovering spatial problems in my sketch.

Also, I decided to make a small painting now because it has been two years since I last worked in a smaller (than my usual 38″ x 58″) size. I am re-using the photograph on which “Epiphany” is based. Using a photograph a second time lets me see how my working methods have evolved over time.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 96

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

My final day at the magic shop [in Disneyland, where he worked as a teenager], I stood behind the counter where I had pitched Svengali decks and the Incredible Shrinking Die, and I felt an emotional contradiction: nostalgia for the present. Somehow, even though I had stopped working only minutes earlier, my future fondness for the store was clear, and I experienced a sadness like that of looking at a photo of an old, favorite pooch. It was dusk by the time I left the shop, and I was redirected by a security guard who explained that a photographer was taking a picture and would I please use the side exit.

I did, and saw a small, thin woman with hacked brown hair aim her large-format camera directly at the dramatically lit castle, where white swans floated in the moat underneath the functioning drawbridge. Almost forty years later, when I was in my early fifties, I purchased that photo as a collectible, and it still hangs in my house. The photographer, it turned out, was Diane Arbus. I try to square the photo’s breathtaking romantic image with the rest of her extreme subject matter, and I assume she saw this facsimile of a castle as though it were a kitsch roadside statue of Paul Bunyan. Or perhaps she saw it as I did: beautiful.

Quoted by A.D. Coleman in Photocritical, May 28, 2014, from Born Standing Up: A Comic’s Life by Steve Martin

Comments are welcome!