Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 682

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Following Julie’s lead, I’d started viewing the everyday the way I looked at art – with an extra beat, with an inquisitive eye, with a willingness to linger on form and ask why. I’d gone into her studio hoping to see art differently. Bit by bit, I saw everything differently. Have you contemplated the forlorn beauty of a stripped-down storefront glowing white on a dark street? Or watched tarps draped on construction sites shiver with the wind? Like nibbling on a magic mushroom, turning an eye on reality makes you feel as if the world is performing just for you.

Bianca Booker in Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey Among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Friends Who Taught Me How to See

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 649

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Some of us spend our entire creative lives digging at the buried parts of ourselves to solve unknown mysteries that we are not even aware of. Unearthing those aspects is not an easy process, because our true psychic reality does not lie in our daily waking thoughts. It exists in the unconscious, in the form of an unfathomable, nonverbal sensory language, one that is so complex and runs so deep that we can only grasp at it, to attain small, amorphous bits. These bits can take any form, even uncharacteristic, surprising ones. We access, process, and finally transform them into what Saint Augustine called ‘visible signs of invisible realities.’

Kate Kretz in Art From Your Core: A Holistic Guide to Visual Voice”

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 643

Sunset over Jersey City

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

What the really great artists do is they’re entirely themselves. They’re entirely themselves, they’ve got their own visions, they have their own way of fracturing reality, and if it’s authentic and true, you will feel it in your nerve endings.

David Foster Wallace quoted in Art From Your Core: A Holistic Guide to Visual Voice by Kate Kretz

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 635

Dinard, Brittany, France

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The body of writing takes a thousand different forms,

and there is no right way to measure.

Changing, changing at the flick of a hand, its various

forms are difficult to capture.

Words and phrases compete with one another, but the

mind is still master.

Caught between the unborn and the living, the writer

struggles to maintain both depth and surface.

He may depart from the square, he may overstep the

circle, searching for the one true form of his reality.

He would fill the eyes of his readers with splendor, he

would sharpen the mind’s values.

The one whose language is muddled cannot do it;

only when mind is clear can language be noble.

Lu Chi quoted in Free Play: Improvisation in Art and Life by Stephen Nachmanovitch

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 625

Downtown Manhattan

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Think of one of those rare, truly exceptional outings to the cinema. In the lobby afterward the experience elicits from us a language of paralysis and disappearance: “I forgot myself. It could have gone on forever.” Stepping out onto the street, we feel that somehow nothing is as it was before. The passing cars, the night sky above the glass towers, the streetlights reflected on the wet pavement: everything glows with a strange immediacy and newness. It is as if the film had done something to the world. A similar thing might happen when we put down a great novel or take in a powerful piece of music.

The Book of Revelation contains a memorable line: “Behold, I make all things new.” Reflecting on this ancient text, the critic Northrop Frye defined the Apocalypse as “the way the world looks once the ego has disappeared.” Every great artistic work is a quiet apocalypse. It tears off the veil of ego, replacing old impressions with new ones at once inexorably alien and profoundly meaningful. Great works of art have a unique capacity to arrest the discursive mind, raising it to a level of reality that is more expansive than the egoic dimension we normally inhabit. In this sense, art is the transfiguration of the world.

J.F. Martel in Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise,Critique, and Call to Action

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 624

Machu Picchu (Peru), June 2016

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

If we were speaking from the point of view of the historian, and if we desired to know as concretely as possible how those peoples of the past or present conceived of their world, we should have to turn to their philosophy to find how they thought about their world, and to their sciences to analyze the atomic factors that contributed to those thoughts, and to their applied arts for the understanding of how this notion appeared when necessarily vulgarized to the common denominator of intelligence. But we would have to turn to their art to understand how they “felt about their world,” to know how their notions of reality found expression in their sensual perception of the world. And we know, of course, how those expressions can differ by simply examining Christian art, which consciously discarded the reality of its predecessor, Greek Hellenistic art.

Mark Rothko in The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 612

New York, NY

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

It is the poet and philosopher who provide the community of objectives in which the artist participates. Their chief preoccupation, like the artist, is the expression in concrete form of their notions of reality. Like him, they deal with verities of time and space, life and death, and the heights of exaltation as well as the depths of despair. The preoccupation with these external problems creates a common ground which transcends the disparity of the means used to achieve them. And it is in the language of the philosopher and poet or, for that matter, of other arts which share the same objective that we must speak if we are to establish some verbal equivalent of the significance of art.

Let us not for a moment conceive that the language of one is interchangeable with that of the other: that one can duplicate the sense of a picture by the sense of words or sounds, or that one can translate the truth of words by means of pictorial delineations. Not all odes of Pindar, framed and embroidered, could duplicate the portrayal by Apelles’ brush of the Hero of the Palaestra. The Pandemonium of Milton or Dante’s Inferno can never replace the vision of the Last Judgment by either Michelangelo or Signorelli. No more so than the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven can be apprehended through the reading of idyllic poems, augmented by descriptions of woodland and fields, of torrents and streams, the study of ornithological sounds, and the laws of harmonics. Neither books on jurisprudence, nor costume plates, can possibly reconstruct Raphael’s School of Athens. And the man who knows a book or a picture through its critics, whatever his experience, has no experience of the art itself. The truth, the reality of each, is confined within its own boundaries and must be perceived in terms of the means generic to itself.

In speaking of art here, there is no thought of recreating the experience of the picture. If we compare one art to another, it is not with the intention of contrasting their actuality, but to speak rather of the motivations and properties such as are admissible to the world of verbal ideas. And if… we are partial to the philosopher – at the expense of those others who share with the artist his common objectives, it is not because we divine in his effort a greater sympathy to the artist, but because philosophy shares with art it’s preoccupation with ideas in the terms of logic.

Mark Rothko in The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 581

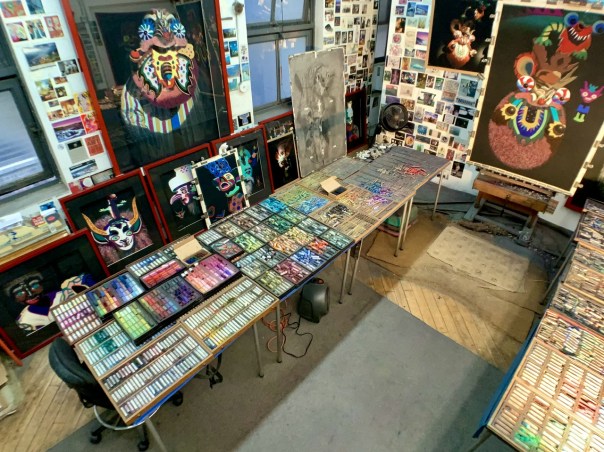

With recent “Bolivianos”

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The essence of style is this: We have something in us, about us; it can be called many things, but for now let’s call it our original nature. We are born with our original nature, but on top of that, as we grow up, we accommodate to the patterns and habits of our culture, family, physical environment, and the daily business of the life we have taken on. What we are taught solidifies as “reality.” Our persona, the mask we show the world, develops out of our experience and training, step by step from infancy to adulthood. We construct our world through the actions of perception, learning, and expectation. We construct our “self” through the same actions of perception, learning, and expectation. World and self interlock and match each other, step by step and shape by shape. If the two constructions, self and world, mesh, we grow from child to adult becoming “normally adjusted individuals.” If they do not mesh so well, we may experience feelings of inner division, loneliness, or alienation.

If we should happen to become artists, our work takes on, to a certain extent, the style of the time: the clothing in which we are dressed by our generation, our country and language, our surroundings, the people who have influenced us.

But somehow, even when we are grown up and “adjusted,” everything we do and are – our handwriting, the vibrato of our voice, the way we handle the bow or breathe into the instrument, our way of using language, the look in our eyes, the pattern of whirling fingerprints on our hand – all these things are symptomatic of our original nature. They all show the imprint of our own deeper style or character.

Stephen Nachmanovitch in Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art

Comments are welcome!