Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 676

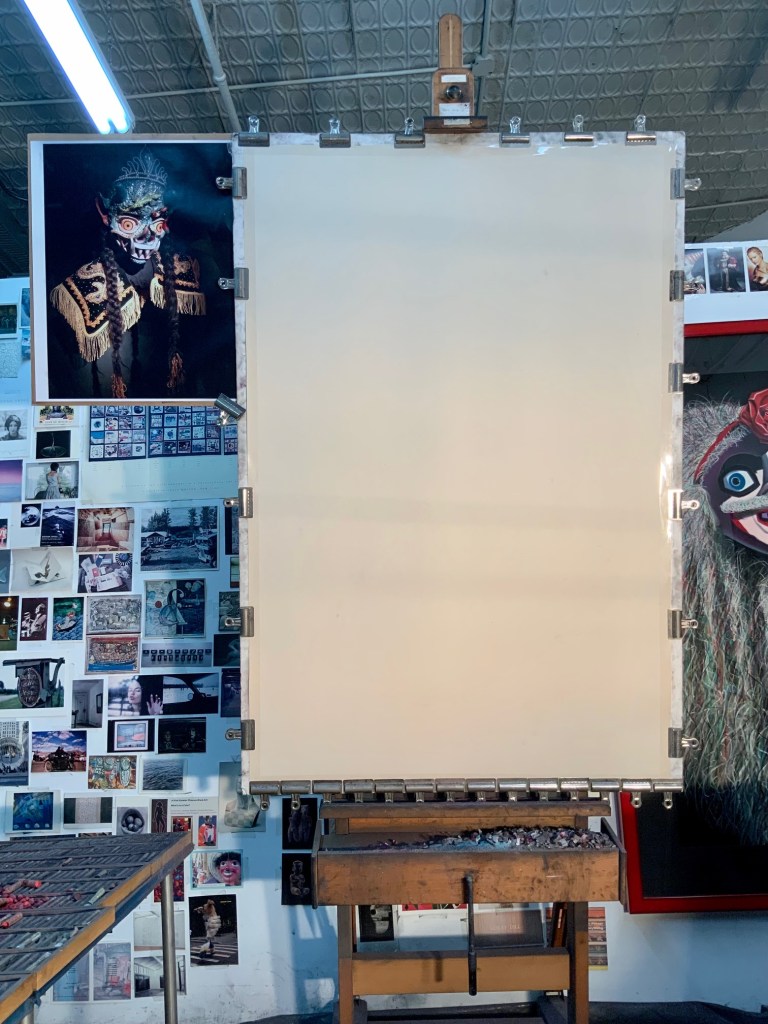

In the Studio

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Henry James once said, ‘The great thing […] the sense of having done the best […] the sense which is the real life of the artist and the absence of which is his death, is having drawn from his own instrument the finest music that nature had hidden in it, of having played it as it should be played. He either does that or he doesn’t […]. and if he doesn’t he isn’t worth speaking of.

Kate Kretz in Art From Your core: A Holistic Guide to Visual Voice

Comments are welcome!

Q: Is there anything you wish you could change about life as a visual artist?

Barbara’s Studio

A: While there is much to admire and maybe even envy about being an artist, it does have some downsides. Among these, for me, is that enormous amounts of solitude are required to create art. I wish this were not the case.

Our work is entirely unique and because it starts as an idea in our heads, we must work solo to bring it into the world. We spend our days pondering, looking, and reacting, rather than speaking to anyone. As typical workdays go, it is rather odd.

I sometimes envy filmmakers who require collaboration with a large team of experts in order to practice their art. They have fellow professionals with whom they can discuss their ideas and they can solicit advice on how to make improvements. Artists rarely have this luxury.

On the other hand, visual artists don’t have to wait for anyone else to do their jobs before we can get to work. We don’t have to deal with personality conflicts or other people’s agendas. Our individual creative process is generally free of obstacles created by others. When you really think about it, the only thing that is required of an artist is to go to the studio and get to work! We are free to make our own rules and our own schedules, and, creatively speaking, are largely responsible for our own advances and setbacks.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 624

Machu Picchu (Peru), June 2016

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

If we were speaking from the point of view of the historian, and if we desired to know as concretely as possible how those peoples of the past or present conceived of their world, we should have to turn to their philosophy to find how they thought about their world, and to their sciences to analyze the atomic factors that contributed to those thoughts, and to their applied arts for the understanding of how this notion appeared when necessarily vulgarized to the common denominator of intelligence. But we would have to turn to their art to understand how they “felt about their world,” to know how their notions of reality found expression in their sensual perception of the world. And we know, of course, how those expressions can differ by simply examining Christian art, which consciously discarded the reality of its predecessor, Greek Hellenistic art.

Mark Rothko in The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 612

New York, NY

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

It is the poet and philosopher who provide the community of objectives in which the artist participates. Their chief preoccupation, like the artist, is the expression in concrete form of their notions of reality. Like him, they deal with verities of time and space, life and death, and the heights of exaltation as well as the depths of despair. The preoccupation with these external problems creates a common ground which transcends the disparity of the means used to achieve them. And it is in the language of the philosopher and poet or, for that matter, of other arts which share the same objective that we must speak if we are to establish some verbal equivalent of the significance of art.

Let us not for a moment conceive that the language of one is interchangeable with that of the other: that one can duplicate the sense of a picture by the sense of words or sounds, or that one can translate the truth of words by means of pictorial delineations. Not all odes of Pindar, framed and embroidered, could duplicate the portrayal by Apelles’ brush of the Hero of the Palaestra. The Pandemonium of Milton or Dante’s Inferno can never replace the vision of the Last Judgment by either Michelangelo or Signorelli. No more so than the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven can be apprehended through the reading of idyllic poems, augmented by descriptions of woodland and fields, of torrents and streams, the study of ornithological sounds, and the laws of harmonics. Neither books on jurisprudence, nor costume plates, can possibly reconstruct Raphael’s School of Athens. And the man who knows a book or a picture through its critics, whatever his experience, has no experience of the art itself. The truth, the reality of each, is confined within its own boundaries and must be perceived in terms of the means generic to itself.

In speaking of art here, there is no thought of recreating the experience of the picture. If we compare one art to another, it is not with the intention of contrasting their actuality, but to speak rather of the motivations and properties such as are admissible to the world of verbal ideas. And if… we are partial to the philosopher – at the expense of those others who share with the artist his common objectives, it is not because we divine in his effort a greater sympathy to the artist, but because philosophy shares with art it’s preoccupation with ideas in the terms of logic.

Mark Rothko in The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 510

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

This excerpt is from “The Blank Page,” published in Last Tales (1957). An old woman who earns her living by storytelling is speaking:

“With my grandmother,” she said, “I went through a hard school. ‘Be loyal to the story,’ the old woman would say to me, ‘Be eternally and unswervingly loyal to the story.’ ‘Why must I be that, grandmother?’ I asked her. ‘Am I to furnish you with reasons, baggage?’ She cried. ‘And you mean to be a story-teller! Why, you are to become a story-teller, and I shall give you the reasons! Hear then: Where the story-teller is loyal, eternally and unswervingly loyal to the story, there, in the end, silence will speak. Where the story has been betrayed, silence is but emptiness. But we, the faithful, when we have spoken our last word, will hear the voice of silence. Whether a small snotty lass understands it or not.’

“Who then, she continues, “tells a finer tale than any of us? Silence does. And where does one read a deeper tale than upon the most precious book? Upon the blank page. When a royal and gallant pen, in the moment of its highest inspiration, has written down its tale with the rarest ink of all – where, then, may one read a still deeper, sweeter, merrier and more cruel tale than that? Upon the blank page.”

Isak Dinesen in Women at Work: Interviews from the Paris Review

Comments are welcome!