Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 97

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

“Art should be independent of all clap-trap – should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like,” he wrote in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies.

Take the picture of my mother, exhibited at the Royal Academy as an “Arrangement in Grey and Black.” Now that is what it is. To me it is interesting as a picture of my mother; but what can or ought the public to care about the identity of the portrait?

James McNeill Whistler quoted in Whistler: The Enraged Genius by Christopher Benfey in The New York Review of Books, June 5, 2014

Comments are welcome!

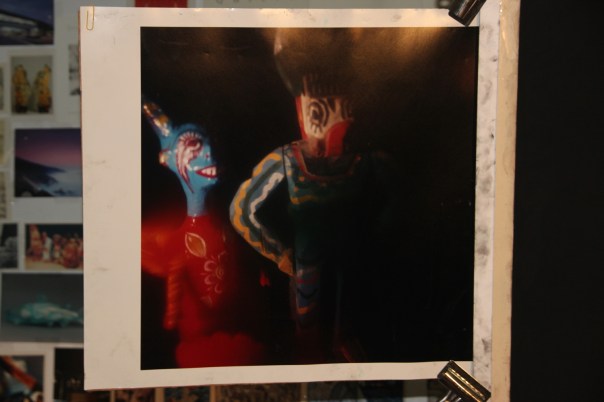

Q: Would you please share a few more of your pastel portraits?

A: See the four above. As in my previous post, I reshot photographs from my portfolio book so the colors above have faded. Many years later, however, my originals are as vibrant as ever.

“Reunion” (bottom) is the last commissioned portrait I ever made. Early on I knew that portraiture was too restrictive and that I wanted my work to evolve in a completely different direction. However, I didn’t know yet what that direction would be.

Comments are welcome!

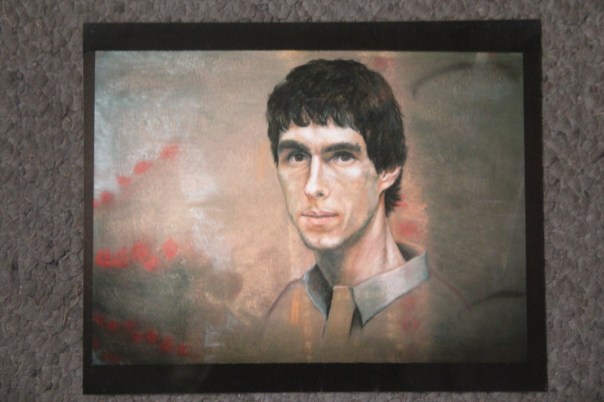

Q: Can we see some of your early potraits?

A: The reproductions above are two of my earliest. The portrait of Bryan (see last week’s post) is hanging at the school that was named for him, Dr. Bryan C. Jack Elementary School, in Tyler, Texas. Krystyn’s portrait is hanging in my dining room in Alexandria, VA – I liked it too much to part with it. I have no idea where the one of John is now.

Note that the actual paintings are more vibrant than the 8 x 10’s shown above. For example, the background of John’s painting is a brilliant green. To obtain the images above I re-photographed photos from my portfolio book. These photos, unlike the originals, have faded over the years. That’s one more reason that my originals need to be seen in person.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Why do you need to use a photograph as a reference source to make a pastel painting?

A: When I was about 4 or 5 years old I discovered that I had a natural ability to draw anything that I could see. It’s the way my brain is wired and it is a gift! One of my earliest memories as an artist is of copying the Sunday comics. Always it has been much more difficult to draw what I CANNOT see, i.e., to recall how things look solely from memory or to invent them outright.

The evolution of my pastel-on-sandpaper paintings has been the opposite of what one might expect. I started out making extremely photo-realistic portraits. I remember feeling highly unflattered when after months of hard work, someone would look at my completed painting and say, “It looks just like a photograph!” I know this was meant as a compliment, but to me it meant that I had failed as an artist. Art is so much more than copying physical appearances.

So I resolved to move away from photo-realism. It has been slow going and part of me still feels like a slacker if I don’t put in all the details. But after nearly three decades I have arrived at my present way of working, which although still highly representational, contains much that is made up, simplified, and/or stylized. As I have always done, I continue to work from life and from photographs, but at a certain point I put everything aside and work solely from memory.

Comments are welcome!