Blog Archives

Q: Would you please share a few more of your pastel portraits?

A: See the four above. As in my previous post, I reshot photographs from my portfolio book so the colors above have faded. Many years later, however, my originals are as vibrant as ever.

“Reunion” (bottom) is the last commissioned portrait I ever made. Early on I knew that portraiture was too restrictive and that I wanted my work to evolve in a completely different direction. However, I didn’t know yet what that direction would be.

Comments are welcome!

Q: How do you organize your studio?

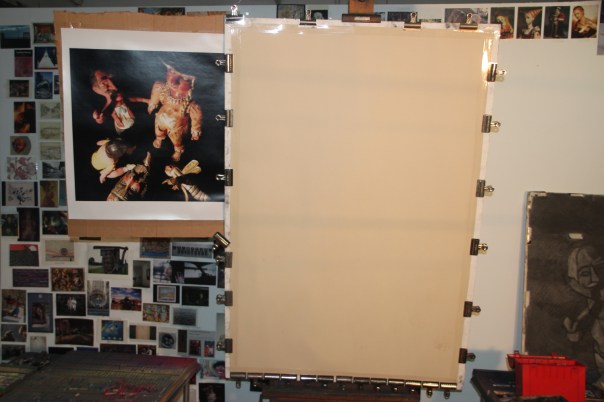

A: Of course, my studio is first and foremost set up as a work space. The easel is at the back and on either side are two rows of four tables, containing thousands of soft pastels.

Enticing busy collectors, critics, and gallerists to visit is always difficult, but sometimes someone wants to make a studio visit on short notice so I am ready for that. I have a selection of framed recent paintings and photographs hanging up and/or leaning against a wall. For anyone interested in my evolution as an artist, I maintain a portfolio book with 8″ x 10″ photographs of all my pastel paintings, reviews, press clippings, etc. The portfolio helps demonstrate how my work has changed during my nearly three decades as a visual artist.

Comments are welcome!

Q: When and why did you start working on sandpaper?

A: In the late 1980s when I was studying at the Art League in Alexandria, VA, I took a three-day pastel workshop with Albert Handel, an artist known for his southwest landscapes in pastel and oil paint. I had just begun working with soft pastel (I’d completed my first class with Diane Tesler) and was still experimenting with paper. Handel suggested I try Ersta fine sandpaper. I did and nearly three decades later, I’ve never used anything else.

The paper (UArt makes it now) is acid-free and accepts dry media, especially pastel and charcoal. It allows me to build up layer upon layer of pigment, blend, etc. without having to use a fixative. The tooth of the paper almost never gets filled up so it continues to hold pastel. If the tooth does fill up, which sometimes happens with problem areas that are difficult to resolve, I take a bristle paintbrush, dust off the unwanted pigment, and start again. My entire technique – slowly applying soft pastel, blending and creating new colors directly on the paper (occupational hazard: rubbed-raw fingers, especially at the beginning of a painting as I mentioned in last Saturday’s blog post), making countless corrections and adjustments, looking for the best and/or most vivid colors, etc. – evolved in conjunction with this paper.

I used to say that if Ersta ever went out of business and stopped making sandpaper, my artist days would be over. Thankfully, when that DID happen, UArt began making a very similar paper. I buy it from ASW (Art Supply Warehouse) in two sizes – 22″ x 28″ sheets and 56″ wide by 10 yard long rolls. The newer version of the rolled paper is actually better than the old, because when I unroll it it lays flat immediately. With Ersta I laid the paper out on the floor for weeks before the curl would give way and it was flat enough to work on.

Comments are welcome!

Q: Why do you have so many pastels?

A: Our eyes can see infinitely more colors than the relative few that are made into pastels. When I layer pigments onto the sandpaper, I mix new colors directly on the painting. The short answer is, I need lots of pastels so that I can make new colors.

I’ve been working exclusively with soft pastel for nearly 27 years. Whenever I feel myself getting into a rut in how I select and use my colors, I look around for new materials to try. I’m in one of those periods now and plan to buy soft pastels made by Henri Roché in Paris. (Not long ago I received a phone call from their artist’s liaison and was offered samples based on my preferences. Wow, what great colors!). Fortunately, new brands of soft pastels are continually coming onto the market. There are pastels that are handmade by artists – I love discovering these – and new ones manufactured by well-known art supply companies. Some sticks of soft pastel are oily, some are buttery, some more powdery, some crumble easily, some are more durable. Each one feels distinct in my hand.

Furthermore, they each have unique mixing properties. It’s an under-appreciated science that I stumbled upon (or maybe I invented it, I’m not sure since I can’t know on a deep level how other pastel painters work). In this respect soft pastel is very different from other paint media. Oil painters, for example, need only a few tubes of paint to make any color in the world. I don’t go in much for studying color theory as a formal discipline. If you want to really understand and learn how to use color, try soft pastel and spend 10,000+ hours (the amount of time Malcolm Gladwell says, in his book, “Outliers,” that it takes to master a skill) figuring it all out for yourself!

Comments are welcome.