Blog Archives

Q: How do you feel about the fact that more people view an artist’s work online than ever see it in person?

A: This has been a dilemma for decades. Don’t get me wrong. Artists are indeed fortunate to have alternative ways to share our art, such as on the internet, but there is just no substitute for seeing art in person! I remember friends telling me about a review of a Nan Goldin exhibition that said, “All of the pleasure circuits are fired in looking.” That rarely happens when you view art online. Yet this is how most people experience our work – at a remove and on a small screen.

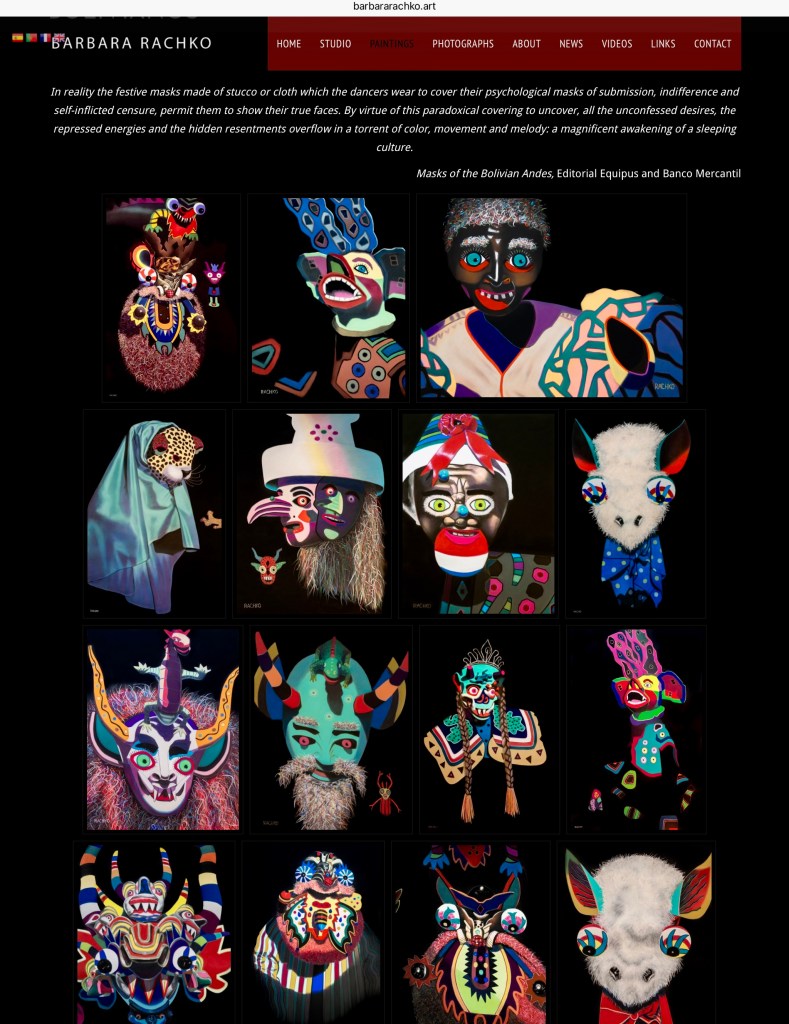

Nowadays, a global audience will see art on their phones instead of in our studios or in a gallery or museum. My pastel paintings are quite large and very detailed so when people finally see them in person, they are often surprised. They had gotten used to seeing them in a much smaller scale online, where very few of the meticulous and subtle details I incorporate into them are visible.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 616

*an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

This may be the most important piece of advice I can give you: The Internet is nothing like a cigarette break. If anything, it’s the opposite. One of the most difficult practical challenges facing writers in this age of connectivity is the fact that the very instrument on which most of us write is also a portal to the outside world. I once heard Ron Carlson say that composing on a computer is like writing in an amusement park. Stuck for a nanosecond? Why feel it? With the single click of a key we can remove ourselves and take a ride on a log flume instead.

By the time we return to work – if, indeed, we return to our work at all – we will be further away from our deepest impulses rather than closer to them. Where were we? Oh, yes. We were stuck. We were feeling uncomfortable and lost. We have gained nothing in the way of waking-dream time. Our thoughts have not drifted, but rather, have ricocheted from one bright and shiny thing to another.

Dani Shapiro in Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life

Comments are welcome!

Q: It must be tricky moving pastel paintings from your New York studio to your framer in Virginia. Can you explain what’s involved? (Question from Ni Zhu via Instagram)

“Impresario” partially boxed for transport to Virginia

A: Well, I have been working with the same framer for three decades so I am used to the process.

Once my photographer photographs a finished, unframed piece, I carefully remove it from the 60” x 40” piece of foam core to which it has been attached (with bulldog clips) during the months I worked on it. I carefully slide the painting into a large covered box for transport. Sometimes I photograph it in the box before I put the cover on (see above).

My studio is in a busy part of Manhattan where only commercial vehicles are allowed to park, except on Sundays. Early on a Sunday morning, I pick up my 1993 Ford F-150 truck from Pier 40 (a parking garage on the Hudson River at the end of Houston Street) and drive to my building’s freight elevator. I try to park relatively close by. On Sundays the gate to the freight elevator is closed and locked so I enter the building around the corner via the main entrance. I unlock my studio, retrieve the boxed painting, bring it to the freight elevator, and buzz for the operator. He answers and I bring the painting down to my truck. Then I load it into the back of my truck for transport to my apartment.

I drive downtown to the West Village, where I live, and double park my truck. (It’s generally impossible to park on my block). I hurry to unload the painting, bring it into my building, and up to my apartment, all the while hoping I do not get a parking ticket. The painting will be stored in my apartment, away from extreme cold or heat, until I’m ready to drive to Virginia. On the day I go to Virginia, I load it back into my truck. Then I make the roughly 5-hour drive south.

Who ever said being an artist is easy was lying!

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 125

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

My own natural proclivity is to categorize the world around me, to remove unfamiliar objects from their dangerous perches by defining, compartmentalizing and labeling them. I want to know what things are and I want to know where they are and I want to control them. I want to remove the danger and replace it with the known. I want to feel safe. I want to feel out of danger.

And yet, as an artist, I know that I must welcome the strange and the unintelligible into my awareness and into my working process. Despite my propensity to own and control everything around me, my job is to “make the familiar strange and the strange familiar,” as Bertolt Brecht recommended: to un-define and un-tame what has been delineated by belief systems and conventions, and to welcome the discomfort of doubt and the unknown, aiming to make visible what has become invisible by habit.

Because life is filled with habit, because our natural desire is to make countless assumptions and treat our surroundings as familiar and unthreatening, we need art to wake us up. Art un-tames, reifies and wakes up the part of our lives that have been put to sleep and calcified by habit. The artist, or indeed anyone who wants to turn daily life into an adventure, must allow people, objects and places to be dangerous and freed from the definitions that they have accumulated over time.

Anne Bogart in What’s the Story: Essays about art, theater, and storytelling

Comments are welcome!

Q: The handmade frames on your large pastel-on-sandpaper paintings are quite elaborate. Can you speak more about them?

A: I have been working in soft pastel since 1986, I believe, and within six years the sizes of my paintings increased from 11″ x 14″ to 58″ x 38.” (I’d like to work even bigger, but the limiting factors continue to be first, the size of mat board that is available and second, the size of my pick-up truck). My earliest work is framed with pre-cut mats, do-it-yourself Nielsen frames, and glass that was cut-to-order at the local hardware store. With larger-sized paintings DIY framing became impractical. In 1989 an artist told me about Underground Industries, a custom framing business in Fairfax, Virginia, run by Rob Plati, his mother, Del, and until last year, Rob’s late brother, Skip. So Rob and Del have been my framers for 24 years. When I finish a painting in my New York studio, I drive it to Virginia to be framed.

Pastel paintings have unique problems – for example, a smudge from a finger, a stray drop of water, or a sneeze will ruin months of hard work. Once a New York pigeon even pooped on a finished painting! Framing my work is an ongoing learning experience. Currently, my frames are deep, with five layers of acid-free foam core inserted between the painting and the mat to separate them. Plexiglas has a static charge so it needs to be kept as far away from the pastel as possible, especially since I do not spray finished pastel paintings with fixative.

Once they are framed, my paintings cannot be laid face down. There’s a danger that stray pastel could flake off. If that happens, the whole frame needs to be taken apart and the pastel dust removed. It’s a time-consuming, labor-intensive process and an inconvenience, since Rob and Del, the only people I trust with my work, are five hours away from New York by truck.

Comments are welcome!