Blog Archives

Q: The handmade frames on your large pastel-on-sandpaper paintings are quite elaborate. Can you speak more about them?

A: I have been working in soft pastel since 1986, I believe, and within six years the sizes of my paintings increased from 11″ x 14″ to 58″ x 38.” (I’d like to work even bigger, but the limiting factors continue to be first, the size of mat board that is available and second, the size of my pick-up truck). My earliest work is framed with pre-cut mats, do-it-yourself Nielsen frames, and glass that was cut-to-order at the local hardware store. With larger-sized paintings DIY framing became impractical. In 1989 an artist told me about Underground Industries, a custom framing business in Fairfax, Virginia, run by Rob Plati, his mother, Del, and until last year, Rob’s late brother, Skip. So Rob and Del have been my framers for 24 years. When I finish a painting in my New York studio, I drive it to Virginia to be framed.

Pastel paintings have unique problems – for example, a smudge from a finger, a stray drop of water, or a sneeze will ruin months of hard work. Once a New York pigeon even pooped on a finished painting! Framing my work is an ongoing learning experience. Currently, my frames are deep, with five layers of acid-free foam core inserted between the painting and the mat to separate them. Plexiglas has a static charge so it needs to be kept as far away from the pastel as possible, especially since I do not spray finished pastel paintings with fixative.

Once they are framed, my paintings cannot be laid face down. There’s a danger that stray pastel could flake off. If that happens, the whole frame needs to be taken apart and the pastel dust removed. It’s a time-consuming, labor-intensive process and an inconvenience, since Rob and Del, the only people I trust with my work, are five hours away from New York by truck.

Comments are welcome!

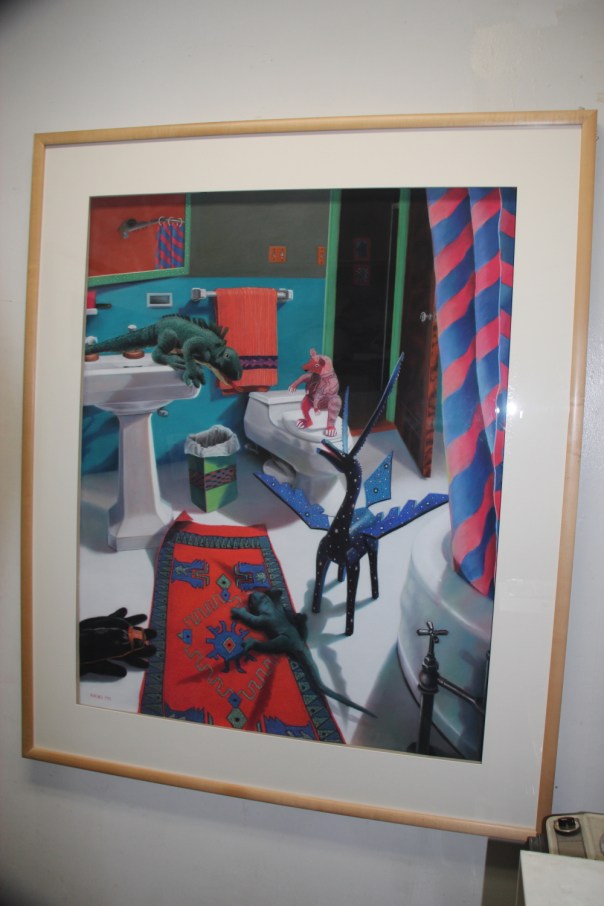

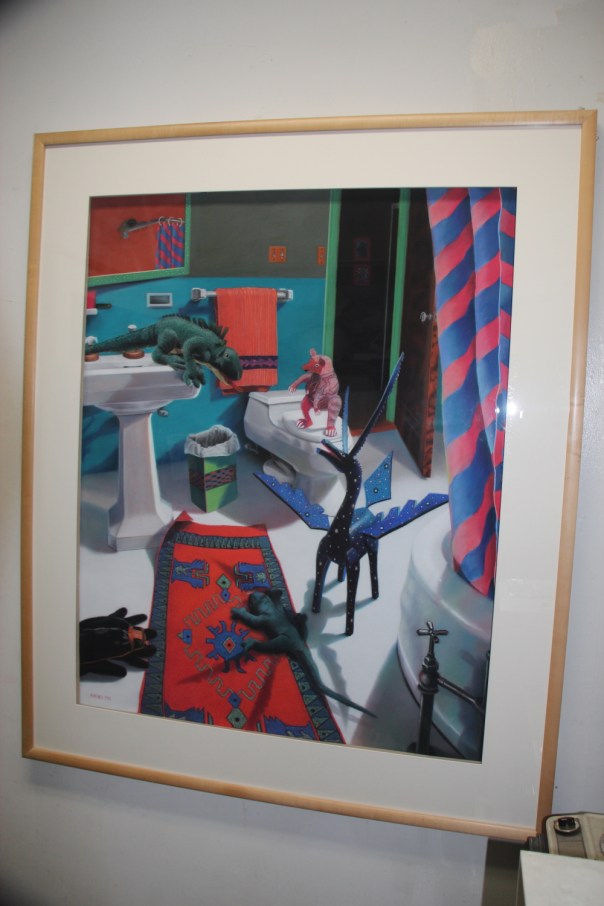

Q: What first intrigued you about Mexico?

A: In the early 90’s my husband, Bryan, and I made our first trip to Oaxaca and to Mexico City. At the time I had become fascinated with the Mexican “Day of the Dead” celebrations so our trip was timed to see them firsthand. Along with busloads of other tourists, we visited several cemeteries in small Oaxacan towns. The indigenous people tending their ancestor’s graves were so dignified and so gracious, even with so many mostly-American tourists tromping around on a sacred night, that I couldn’t help being taken with these beautiful people and their beliefs. From Oaxaca we traveled to Mexico City, where again I was entranced, but this time by the rich and ancient history. On our first trip we visited the National Museum of Anthropology, where I was introduced to the fascinating story of ancient Meso-American civilizations (it is still one of my favorite museums in the world); the ancient city of Teotihuacan, which the Aztecs discovered as an abandoned city and then occupied as their own; and the Templo Mayor, the historic center of the Aztec empire, infamous as a place of human sacrifice. I was astounded! Why had I never learned in school about Mexico, this highly developed cradle of western civilization in our own hemisphere, when so much time had been devoted to the cultures of Egypt, Greece, and elsewhere? When I returned home to Virginia I began reading everything I could find about ancient Mexican civilizations, including the Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Aztec, and Maya. This first trip to Mexico opened up a whole new world and was to profoundly influence my future work. I would return there many more times.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 21

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

It is the beginning of a work that the writer throws away.

A painting covers its tracks. Painters work from the ground up. The latest version of a painting overlays earlier versions, and obliterates them. Writers, on the other hand, work from left to right. The discardable chapters are on the left. The latest version of a literary work begins somewhere in the work’s middle, and hardens toward the end. The earlier version remains lumpishly on the left; the work’s beginning greets the reader with the wrong hand. In those early pages and chapters anyone may find bold leaps to nowhere, read the brave beginnings of dropped themes, hear a tone since abandoned, discover blind alleys, track red herrings, and laboriously learn a setting now false.

Several delusions weaken the writer’s resolve to throw away work. If he has read his pages too often, those pages will have a necessary quality, the ring of the inevitable, like poetry known by heart; they will perfectly answer their own familiar rhythms. He will retain them. He may retain those pages if they possess some virtues, such as power in themselves, though they lack the cardinal virtue, which is pertinence to, and unity with, the book’s thrust. Sometimes the writer leaves his early chapters in place from gratitude; he cannot contemplate them or read them without feeling again the blessed relief that exalted him when the words first appeared – relief that he was writing anything at all. That beginning served to get him where he was going, after all; surely the reader needs it, too, as groundwork. But no.

Every year the aspiring photographer brought a stack of his best prints to an old, honored photographer, seeking his judgment. Every year the old man studied the prints and painstakingly ordered them into two piles, bad and good. Every year the old man moved a certain landscape print into the bad stack. At length he turned to the young man: “You submit this same landscape every year, and every year I put it in the bad stack. Why do you like it so much?” The young photographer said, “Because I had to climb a mountain to get it.”

Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Comments are welcome!

Q: Why do you work in series?

A: I don’t really have any choice in the matter. It’s more or less the way I have always worked so it feels natural. Art-making comes from a deep place. In keeping with the aphorism ars longa, vita brevis, it’s a way of making one’s time on earth matter. Working in series mimics the more or less gradual way that our lives unfold, the way we slowly evolve and change over the years. Life-altering events happen, surely, but seldom do we wake up drastically different – in thinking, in behavior, etc. – from what we were the day before. Working in series feels authentic. It helps me eke out every lesson my paintings have to teach. With each completed piece, my ideas progress a step or two further.

Last week I went to the Metropolitan Museum to see an exhibition called, “Matisse: In Search of True Painting.” It demonstrates how Matisse worked in series, examining a subject over time and producing multiple paintings of it. Matisse is my favorite artist of any period in history. I never tire of seeing his work and this particular exhibition is very enlightening. In fact, it’s a must-see and I plan to return, something I rarely do because there is always so much to see and do in New York. As I studied the masterpieces on the wall, I recognized a kindred spirit and thought, “Obviously, working in series was good enough for Matisse!”

Comments are welcome!

Q: Why do you have so many pastels?

A: Our eyes can see infinitely more colors than the relative few that are made into pastels. When I layer pigments onto the sandpaper, I mix new colors directly on the painting. The short answer is, I need lots of pastels so that I can make new colors.

I’ve been working exclusively with soft pastel for nearly 27 years. Whenever I feel myself getting into a rut in how I select and use my colors, I look around for new materials to try. I’m in one of those periods now and plan to buy soft pastels made by Henri Roché in Paris. (Not long ago I received a phone call from their artist’s liaison and was offered samples based on my preferences. Wow, what great colors!). Fortunately, new brands of soft pastels are continually coming onto the market. There are pastels that are handmade by artists – I love discovering these – and new ones manufactured by well-known art supply companies. Some sticks of soft pastel are oily, some are buttery, some more powdery, some crumble easily, some are more durable. Each one feels distinct in my hand.

Furthermore, they each have unique mixing properties. It’s an under-appreciated science that I stumbled upon (or maybe I invented it, I’m not sure since I can’t know on a deep level how other pastel painters work). In this respect soft pastel is very different from other paint media. Oil painters, for example, need only a few tubes of paint to make any color in the world. I don’t go in much for studying color theory as a formal discipline. If you want to really understand and learn how to use color, try soft pastel and spend 10,000+ hours (the amount of time Malcolm Gladwell says, in his book, “Outliers,” that it takes to master a skill) figuring it all out for yourself!

Comments are welcome.

Pearls from artists* # 14

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

The tendency to complete a Gestalt is so strong that it is surprising so many people have trouble finishing tasks. It just shows the inherent difficulty of getting anything physical accomplished. Matter is stubborn. Only dogged effort brings a concept into an arena in which it can demand the serious attention we give a challenge to our own physical selves. It is here that “conceptual art” tends to be, using Alexandra’s (Truitt’s daughter) adjective, “lame.” The concept, remaining merely conceptual, falls short of the bite of physical presence. Just one step away is the debilitating idea that a concept is as forceful in its conception as in its realization.

I see that this might be considered an intelligent move. The world is cluttered with objects anyway. The ideas in my head are invariably more radiant than what is under my hand. But something puritanical and tough in me won’t take that fence. The poem has to be written, the painting painted, the sculpture wrought. The beds have to be made, the food cooked, the dishes done, the clothes washed and ironed. Life just seems to me irremediably about coping with the physical.

Ann Truitt, Daybook: The Journal of an Artist

Comments are welcome.