Blog Archives

Pearls from artists* # 59

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

Friends sometimes ask, “Don’t you get lonely sitting by yourself all day?” At first it seemed odd to hear myself say No. Then I realized that I was not alone; I was in the book; I was with the characters. I was with my Self.

Not only do I not feel alone with my characters; they are more vivid and interesting to me than the people in my real life. If you think about it, the case can’t be otherwise. In order for a book (or any project or enterprise) to hold our attention for the length of time it takes to unfold itself, it has to plug into some internal perplexity or passion that is of paramount importance to us. The problem becomes the theme of our work, even if we can’t at the start understand or articulate it. As the characters arise, each embodies infallibly an aspect of that dilemma, that perplexity. These characters might not be interesting to anyone else but they’re absolutely fascinating to us. They are us. Meaner, smarter, sexier versions of ourselves. It’s fun to be with them because they’re wrestling with the same issue that has its hooks into us. They’re our soul mates, our lovers, our best friends. Even the villains. Especially the villains.

Stephen Pressfield in The War of Art

Comments are welcome!

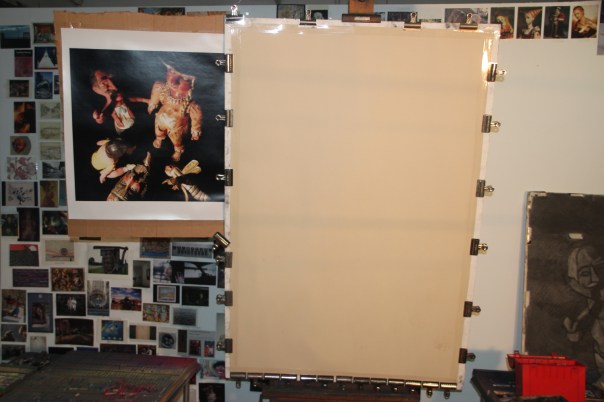

Q: When and why did you start working on sandpaper?

A: In the late 1980s when I was studying at the Art League in Alexandria, VA, I took a three-day pastel workshop with Albert Handel, an artist known for his southwest landscapes in pastel and oil paint. I had just begun working with soft pastel (I’d completed my first class with Diane Tesler) and was still experimenting with paper. Handel suggested I try Ersta fine sandpaper. I did and nearly three decades later, I’ve never used anything else.

The paper (UArt makes it now) is acid-free and accepts dry media, especially pastel and charcoal. It allows me to build up layer upon layer of pigment, blend, etc. without having to use a fixative. The tooth of the paper almost never gets filled up so it continues to hold pastel. If the tooth does fill up, which sometimes happens with problem areas that are difficult to resolve, I take a bristle paintbrush, dust off the unwanted pigment, and start again. My entire technique – slowly applying soft pastel, blending and creating new colors directly on the paper (occupational hazard: rubbed-raw fingers, especially at the beginning of a painting as I mentioned in last Saturday’s blog post), making countless corrections and adjustments, looking for the best and/or most vivid colors, etc. – evolved in conjunction with this paper.

I used to say that if Ersta ever went out of business and stopped making sandpaper, my artist days would be over. Thankfully, when that DID happen, UArt began making a very similar paper. I buy it from ASW (Art Supply Warehouse) in two sizes – 22″ x 28″ sheets and 56″ wide by 10 yard long rolls. The newer version of the rolled paper is actually better than the old, because when I unroll it it lays flat immediately. With Ersta I laid the paper out on the floor for weeks before the curl would give way and it was flat enough to work on.

Comments are welcome!

Pearls from artists* # 21

* an ongoing series of quotations – mostly from artists, to artists – that offers wisdom, inspiration, and advice for the sometimes lonely road we are on.

It is the beginning of a work that the writer throws away.

A painting covers its tracks. Painters work from the ground up. The latest version of a painting overlays earlier versions, and obliterates them. Writers, on the other hand, work from left to right. The discardable chapters are on the left. The latest version of a literary work begins somewhere in the work’s middle, and hardens toward the end. The earlier version remains lumpishly on the left; the work’s beginning greets the reader with the wrong hand. In those early pages and chapters anyone may find bold leaps to nowhere, read the brave beginnings of dropped themes, hear a tone since abandoned, discover blind alleys, track red herrings, and laboriously learn a setting now false.

Several delusions weaken the writer’s resolve to throw away work. If he has read his pages too often, those pages will have a necessary quality, the ring of the inevitable, like poetry known by heart; they will perfectly answer their own familiar rhythms. He will retain them. He may retain those pages if they possess some virtues, such as power in themselves, though they lack the cardinal virtue, which is pertinence to, and unity with, the book’s thrust. Sometimes the writer leaves his early chapters in place from gratitude; he cannot contemplate them or read them without feeling again the blessed relief that exalted him when the words first appeared – relief that he was writing anything at all. That beginning served to get him where he was going, after all; surely the reader needs it, too, as groundwork. But no.

Every year the aspiring photographer brought a stack of his best prints to an old, honored photographer, seeking his judgment. Every year the old man studied the prints and painstakingly ordered them into two piles, bad and good. Every year the old man moved a certain landscape print into the bad stack. At length he turned to the young man: “You submit this same landscape every year, and every year I put it in the bad stack. Why do you like it so much?” The young photographer said, “Because I had to climb a mountain to get it.”

Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Comments are welcome!