Category Archives: 2012

2012 Archives

Q: If your “actors” could talk, what might they say about you as a director?

A: I hope they would say that I am very focused, devoted to doing the best work possible, that I know exactly what I am after, and that I use all the skills and knowledge I have acquired over many years as a painter and a photographer to make art that is worthwhile and meaningful.

Q: Your paintings are full-blown productions. You take great care to not only cast them, but to choose the right sets and lighting for them. Would you consider making films?

A: In the late 1990s I seriously considered it – I studied film at the New School and at New York University – but ultimately I decided to stay with painting. A well-made film will be seen by more people than a painting ever will, but the finances of making it are daunting. Historically visual artists have achieved mixed results when they have turned to filmmaking. Cindy Sherman was not very good at it, but Shirin Neshat’s feature film was very good. Julian Schnabel is arguably a much better filmmaker than he ever was a painter. Most importantly for me, filmmaking is a very complex collaboration. I love the time I spend alone in my studio and prefer having control over and being fully responsible for the results. It would be difficult to give this up.

Q: There is plenty of joyful and vibrant color in your work, but shadows are also ever-present. I would almost go as far as calling them the supporting players of your compositions. Can you elaborate on their importance and significance?

A: When I arrange the setups, I spend a lot of time lighting them, mainly in a search for intriguing cast shadows. At one point in the “Domestic Threats” series the shadows became so important that I thought of them as physical objects in their own right. So I made them very prominent, outlined them, and otherwise gave them added emphasis. Often they had no relation to the actual objects as I created any shadow shapes that looked interesting in the painting. When I go to art galleries and museums, I always look at the shadows surrounding well-lit three dimensional objects. I find shadows quite fascinating. How less visually satisfying Calder’s mobiles and stabiles would be without the cast shadows!

Q: In your paintings, we occasionally catch a glimpse of a blond-haired female whom I assume is you. Are you also playing a character or do you appear as yourself?

A: I am playing myself. I like to include myself in a painting now and then. I used to be a portrait artist and this is one way to keep up my technical skills. Beyond that when I’m in the painting it gives another level of reality to the scene depicted. I painted “No Cure for Insomnia” (above) at a time when I was having trouble sleeping. In it I imagined what people who didn’t know me personally, but who only knew my work, might think was keeping me up at night!

Q: Do the figures go on to play different roles in different paintings or are their characters recurring?

A: The dolls and other objects play different roles in each painting and I paint them differently to reflect this. If you take one figure and follow it through the series, you’ll notice that it evolves quite a bit. I continue to think of each figure as an actor in a repertory company.

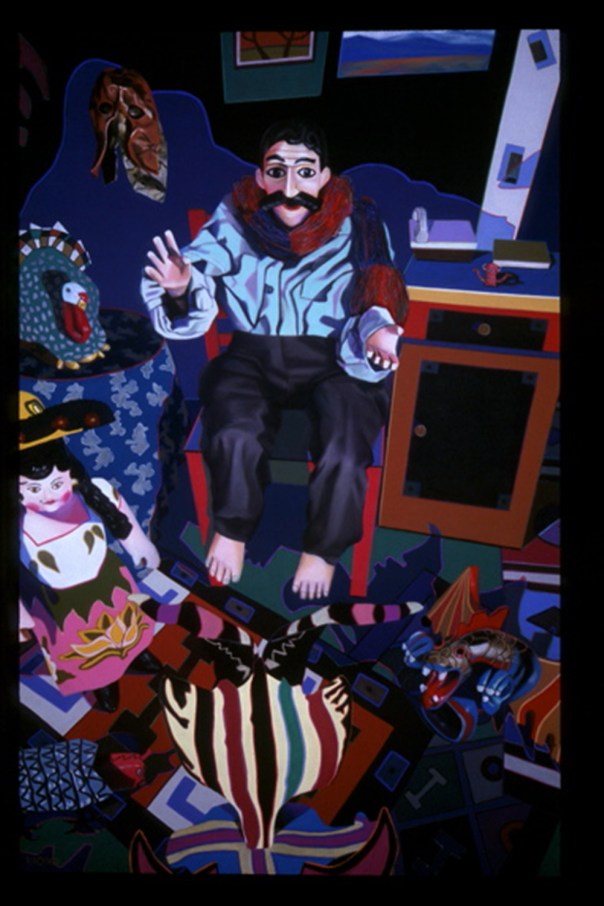

Q: Can you elaborate on the series title, “Domestic Threats?”

A: All of the paintings in this series are set in places where I reside or used to live, either a Virginia house or New York apartments, i.e., domestic environments. Each painting typically contains a conflict of some sort, at least one figure who is being menaced or threatened by a group of figures. So I named the series “Domestic Threats.” Depending on what is going on in the country at a particular moment in time, however, people have seen political associations in my work. Since my husband was killed on 9/11, many people thought the title, “Domestic Threats,” was prescient. They have ascribed all kinds of domestic terrorism associations to it, but that is not really what I had in mind. For a time some thought I was hinting at scenes of domestic violence, but that also is not what I had intended. “Domestic Threats” seems to be fraught with associations that I never considered, but it’s an apt title for this work.

Q: In your earlier “Domestic Threats” series, you liken your paintings to scenes in a movie. Is there an audition process? What qualities must a figure possess to be cast in one of your paintings?

A: There’s not an audition process, but I do feel like the masks and figures call out to me when I’m searching the markets of Mexico and Guatemala. Color is very important – the brighter and the more eye-catching the better – plus they must have lots of “personality.” I try not to buy anything mass-produced or obviously made for tourists. How and where these objects come into my life is an important part of the process. Getting them back to the U.S. is always an adventure. For example, in 2010 I was in Panajachel on the shores of Lake Atitlan in Guatemala. After returning from a boat ride across the lake, my friends and I were walking back to our hotel when we noticed a mask store. This store contained many beautiful things so I spent a long time looking around. Finally, I made my selections and was ready to buy five standing wooden figures, when I learned that Tomas, the store owner, did not accept credit cards. Not having enough cash, I was heart-broken and thought, “Oh, no. I can’t bring these home.” However, thanks to my friend, Donna, whose Spanish was much more fluent than mine, Tomas and she came up with a plan. I would pay for the figures at a nearby hotel and once the owner was paid by the credit card company, he would pay Tomas. Fabulous! Tomas, Donna, and I walked to the hotel, where the transaction was completed. Packing materials are not so easy to find in remote parts of Guatemala so the packing and shipping arrangements took another hour. During the negotiations Tomas and I became friends. We exchanged telephone numbers (he didn’t have a telephone so he gave me the phone number of the post office next door, saying that when I called, he could easily run next door). When I returned to New York ten days later, the package was waiting for me.

While setting up a scene for a painting, I work very intuitively so how the objects are actually “cast” is difficult to say. Looks count a lot – I select an object and put it in a particular place, move it around, and develop a storyline. I spend time arranging lights and looking for interesting cast shadows. I shoot two exposures with a 4 x 5 view camera and order a 20″ x 24″ photograph to use for reference. I also work from the “live” objects. My series, “Domestic Threats,” was initially set in my Virginia house, but in 1997, I moved to a six floor walk-up in New York. For the next few years the paintings were set there, until 2001 when I moved to my current apartment. In a sense the series is a visual autobiography that hints at what my domestic surroundings were like.

Q: How large is your collection of Mexican folk art objects?

A: I haven’t counted them, but my guess is 200 pieces of various sizes. This includes the Guatemalan figures. I went to Guatemala in 2009 and 2010. Since I divide my time between a house in Alexandria, VA, an apartment in Manhattan, and a studio in Chelsea, part of my folk art collection is in each of these places.

Q: Mexico has been a big influence on your work. What first drew you to Mexican folk art – masks, carved wooden animals, papier mâché figures, and toys?

A: In 1991 my future sister-in-law sent, as a Christmas present, two brightly painted wooden figures from Oaxaca. One was a large, blue and white polka dot flying horse, the other a bear, painted with red, white, and black dots and lines.

At the time I was living in Alexandria, Virginia, studying at the Art league School there, and working as a full-time artist. I had resigned from the Navy after seven years on active duty, although I still worked one weekend a month at the Pentagon as a reservist. I was looking for something new to paint with soft pastel, having found portraits deeply unsatisfying.

I had never seen anything like these Oaxacan figures and was intrigued. I started asking friends about Oaxaca and soon learned that the city has a unique style of painting, the self-titled Oaxacan school, and that the painter, Rufino Tamayo, and husband and wife photographers, Manuel and Lola Alvarez Bravo, were from Oaxaca. (Manuel Alvarez Bravo founded an important photography museum there).

I had been a fan of Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and other artists associated with Mexico, and had a long-standing interest in pre-Columbian civilizations. I knew some Spanish, having studied it in high school. I began reading everything I could find about Oaxaca and Mexico and soon became fascinated with the Day of the Dead.

In 1992 my future husband, Bryan, and I made our first trip to Mexico, spending a week in Oaxaca to see Day of the Dead observances and to study the Mixtec and Zapotec ruins (Monte Alban, Yagul, Mitla, etc.), and another week in Mexico City to visit Diego Rivera’s murals at the Ministry of Education, Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul, and nearby ancient archeological sites (the Templo Mayor, Teotihuacan, etc.).

I began collecting Mexican folk art on that first trip. I still have fond memories of buying my first mask, a big wooden dragon with a Conquistador’s face on its back. Bryan and I found it high on a wall in a dusty Oaxacan shop. The dragon was three and a half feet long and three feet wide. Because it was fragile, we hand-carried it onto the plane and were able to store it in the first class cabin (this was pre-9/11). I chuckle to remember that we covered its finely carved toes with rolled up socks to prevent them from breaking!

I have been back to Mexico many times, mainly visiting the central and southern states. I travel there to study pre-Columbian history, archaeology, mythology, culture, and the arts. It is an endlessly fascinating country that has long been an inspiration for artists.